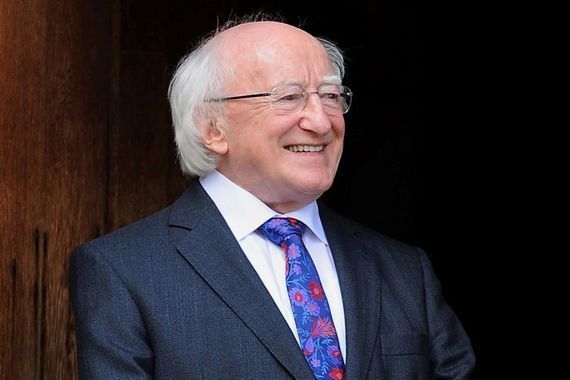

Michael D. Higgins is well over halfway through his second – and final – term as president of Ireland, and it’s safe to assume that he already has one eye on history and how his legacy will be assessed.

The truth is that Higgins is impossible to pigeonhole. He is not making it easy for future historians as over the last 12 months he has left some hostages to fortune, and none more so than in the past two weeks.

During that time he has jolted the political ruling classes at home by questioning their competence on housing policy and has been greeted with disbelief internationally by blaming a sectarian massacre in Nigeria on climate change. There is a sense that with this president there is more to come as he appears frustrated with the shackles that his role imposes on him.

While opening a new housing development in Kildare dedicated to providing housing for young people coming from homelessness, Higgins passionately called out the Irish government’s housing policy. It was, he said, not so much a policy failure as a disaster, and that housing should never have been left to the marketplace.

Read more

He compared the policy to the dreaded British Poor Law system of the 19th century which housed the poor in workhouses, except that this time, he said, it had a harp on it, the symbol of the government of Ireland. It was a devastating and targeted critique of the government from an economic, historical, and social care perspective.

The message was clear. The president had lost confidence in the government to deal with the crisis.

It is hard to find a single person that disagrees with what he said, but the question is, was it his business to be so openly critical of the government which technically under the Constitution he appointed on the recommendation of the Dail?

It has always been a central tenet of the relationships between government and the presidency that the latter was above criticism and in turn, would not use his/her position in Áras an Uachtaráin to comment on political matters. But precedent is there to be ignored, and never before has an incumbent used the office as a bully pulpit to comment on controversies of the day and to so devastatingly criticize those in power.

In the days following his speech, the response from government was mixed. Tánaiste Leo Varadkar essentially said nothing to see here, we all know there is a problem.

Taoiseach Micheál Martin was more pointed, stating that the government had a housing policy and that in time it would work, while a backbench TD was trotted out on the airways to criticize Higgins, stating that his analysis was simplistic and that he was playing fast and loose with accepted protocols.

If Higgins is changing the nature of the job, then expect the government to react accordingly and push back. That’s when it could get very interesting as Higgins, as well as being passionate, has more than his fair share of pomposity.

The last president offended by a government was Cearbhall O Dalaigh, and that didn’t end well as he resigned causing a constitutional crisis. Higgins, for his part, is acutely aware of slights whether real or imagined.

Take, for example, one of the stated reasons why he didn’t attend the religious service in the North last year to commemorate partition. Part of the reason, he said, was that the invitation referred to him as the president of the Republic of Ireland, when, in fact, he is the President of Ireland.

Turns out that this was nonsense and that he had always been given his correct title on official invitations. Higgins had to walk back on that one.

For now, though, Higgins has gotten away with what he said about homeless policy, but no government can survive long if it is being undermined on a regular basis by the head of state. Next time he uses such strident language to criticize the executive branch of government, expect a full-blown constitutional crisis.

The other event in the past fortnight that he had to change tack on was his bizarre, some would say outrageous, claim that the recent sectarian church massacre in Nigeria was a result of climate change.

On Sunday, June 5, gunmen associated with the Islamic State attacked a Catholic church in southwest Nigeria during Mass, killing at least 40 people. Higgins, in his statement, condemned the attack and linked it to climate change and food security.

The attack in a church "is a source of particular condemnation, as is any attempt to scapegoat pastoral peoples who are among the foremost victims of the consequences of climate change.”

He added, “The neglect of food security issues in Africa for so long has brought us to a point of crisis that is now having internal and regional effects based on struggles, ways of life themselves.”

Quick to respond was the Bishop Badejo of Oyo, the diocese in which the attack occurred, who said Higgins’ statement was incorrect and far-fetched and deflected from the truth of what happened.

“To suggest or make a connection between victims of terror and consequences of climate change is not only misleading but also exactly rubbing salt to the injuries of all who have suffered terrorism in Nigeria,” he added.

Irish missionaries built the church that was attacked, and the first two bishops of the dioceses were Irishmen. Sister Kathleen McGarvey, provincial leader in Ireland of the Missionary Sisters of Our Lady of Apostles, who has spent many years in Nigeria, said Higgins’ “use of words reveals the ignorance of our leaders, whether conscious or unconscious, of the alarming spread of insecurity and violence in Nigeria.”

Clearly stung, Higgins issued a clarification where he claimed that he did not link climate change to the massacre, asking us in effect to ignore the evidence in front of our own eyes. It was the Humpty Dumpty defense: words mean what I choose them to mean, neither more nor less.

This leads us to perhaps the most successful aspect of the man, namely Higgins the politician, astute reader of the public mood, capable of changing his mind if it suits his agenda. His second term as president was never in doubt once he stitched up any potential candidate from the major parties by refusing to declare as a candidate until the last possible moment.

In running again he reneged on his promise to serve one seven-year term. But it made no difference to his popularity, and his re-election saw him receive the highest number of votes ever by an Irish candidate.

Although future historians will have a lot to work with in assessing his legacy, it is unlikely his term in office will be seen as transformational as Mary Robinson’s was. That is, providing he sees out his second term and doesn’t implode in a bout of self-righteousness.

There will be many sleepless nights spent by politicians and civil servants alike trying to ensure that doesn’t happen.

Comments