Is the abortion questions as simple as that? Is it a woman's right to choose or is that merely a cop out?

The basic argument of those who want abortion introduced in Ireland -- and the most vocal campaigners are young women -- is reflected in the slogan on their posters: It's a Woman's Right to Choose.

This is based on the belief that, whatever other issues are involved, the final say must always be that of the woman who is pregnant. It is her bodily integrity that is at stake.

She must have the right to decide what she wants to do with her own body. No one else has the right to decide on her behalf -- and possibly against her wishes -- what is best for her.

It's a simple but very powerful argument. Speaking as a man and a somewhat uncertain supporter of a woman's right to choose, it must also be said that it's an easy way out for many people, especially men, who feel conflicted about abortion.

In fact it would be fair to say that for many men it's a cop out. Rather than grappling with the very difficult issues involved, it's far easier for a man to say that at the end of the day it's a woman's right to choose.

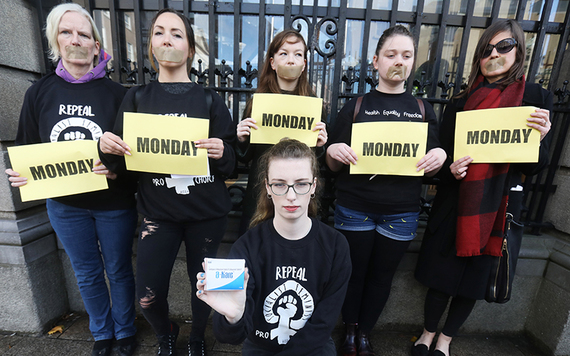

Anti-abortion protesters.

Except that we all know it's not as simple as that, because there is more than one life involved. If it were as simple as that and a woman's right to choose is absolute, why do most countries put legal time limits on abortion?

As soon as we accept that a woman's right to choose is not absolute and has time limits attached, then we enter into the fraught discussion of what time limits are reasonable. Before you know it we are immersed in arguments about when life begins, whether it is at the moment of conception (the Catholic Church position) or when a baby can survive outside the womb (a widely held view), or some time in the middle, or some time later.

The moral, ethical and legal questions involved are endless and endlessly complicated. And we are going to hear many of them debated in the coming months in the run up to a referendum on abortion here which the government has promised to hold this summer.

This referendum will be seeking to repeal the 1983 Eighth Amendment to the Constitution which gave an unborn child and its mother an equal right to life. The effect was to copper-fasten the illegality of abortion in Ireland except in the most extreme cases in which the mother's life was in danger and intervention to save her meant the loss of her baby as an unintended, secondary consequence.

Pro-Repeal the Eighth march on O'Connell Street, in 2017.

Abortion had always been illegal in Ireland, but there were concerns back then among conservative Catholics that a more liberal attitude to abortion in other countries could lead to creeping change here. The 1983 amendment to the Constitution prevents any law being introduced by the Dail to allow abortion here without the consent of the people in another referendum. Which is why the first step now in changing our abortion law is another referendum to repeal the Eighth Amendment.

The pressure for change has been intense in recent years and for very good reasons. Ireland has developed radically since 1983 and we are now a younger, more secular country. This has meant that many people here, especially younger people, are no longer willing to live with the pretense that abortion is not necessary when the reality is that thousands of Irish women are going to Britain every year to have their abortions there.

Modification of the abortion ban here a few years ago (mainly to do with threatened suicide) has meant little difference to this hypocritical situation. The reforms are so restrictive that they exclude most women who want an abortion, which is why the vast majority still has to travel abroad, despite the difficulties involved.

There is a more recent additional factor -- the growing number of Irish women who are accessing abortion pills on the web and using them without any medical advice. These pills are illegal here and are seized by customs when spotted, but many get through.

A 2016 paper in the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology estimated that 1,600 women in Ireland and Northern Ireland had abortion pills sent to them by one web-based service over the previous three years. That was just one supplier and it was over three years ago. It would be reasonable to assume that the use has grown substantially since then.

Repeal the Eighth protest the reality that Irish women are taking abortion pills.

Those campaigning to repeal the Eighth believe that it is now time that Ireland had a general abortion service like the U.K. and other European countries. It is their absolute determination to change the present shameful situation -- as well as the tragic cases in which women here have died because abortion is so restricted -- which led to Taoiseach Leo Varadkar's promise to tackle the issue.

But it's not just the new socially progressive taoiseach who is on board. The change in public mood has been noted by politicians here on all sides. They are aware that the population now is more liberal and diverse, and that the influence of the Catholic Church has declined.

One indicator of how much Ireland has changed in recent years was the successful vote in 2015 to legalize same-sex marriage. Also notable was the size of the pro-abortion marches and rallies last year demanding action.

Read more: Irish artists campaign to repeal the 8th Amendment

In spite of the general momentum towards change, however, politicians have approached the abortion issue with extreme caution, remembering how it tore the country apart back in 1983. So rather than approach the issue directly themselves, the government set up a Citizens Assembly in 2016 to discuss abortion.

The assembly reported last year, with a large majority favoring the repeal of the Eighth Amendment and 64 percent in favor of abortion effectively on demand. Of those, 48 percent voted in favor of termination without restriction up to 12 weeks, and 44 percent up to 22 weeks (the limit in the U.K. is 24 weeks). The grounds for termination are so wide (from suicidal feelings to a woman's socio-economic situation) that it is effectively abortion on demand.

The report of the Citizens Assembly was sent to an all-party Oireachtas committee last year for further consideration of what should be done. The committee also heard evidence from medical and other experts before issuing its report recently, recommending the repeal of the Eighth and a time limit of 12 weeks. And at that point it was over to the government to decide on policy and start the process for change.

That began last week when there was a two-day debate in the Dail about abortion, the beginning of the process which will lead to the referendum this year. All the main political parties have already said that there will be a free vote on the issue which takes politics out of it and leaves it up to the individual politicians. And that freedom was already evident last week in the sincerity of the opinions offered in the Dail debate.

One newspaper here has already done a poll of the Dail and Senate which shows a clear majority in favor of change. However, opinion is divided almost equally between the politicians who say they will vote for change, and those who are either against change or are undecided or refusing to say.

As always, there are those who will only declare when they see which way the wind is blowing. The taoiseach himself is being cautious, having said that he thinks abortion on demand up to a 12 week limit may be more than many people here are comfortable with.

Ireland's leader Leo Varadkar, a qualified doctor, is being cautious about his views.

That disappointed those who are leading the campaign for change. More astute political observers, however, believe Varadkar is trying to reassure middle ground voters and draw them into the discussion.

The big surprise in the debate last week was the speech by the Fianna Fail leader Micheal Martin in which he backed both repeal and an acceptance of a 12-week time limit in subsequent abortion legislation. He has always been pro-life, so this switch without any advance warning was unexpected. It was a real shock to many Fianna Fail members, not least because the party convention last year voted against the introduction of unrestricted abortion by a strong majority.

Martin's stance has won praise from campaigners and commentators for his courageous leadership. His position and its influence on Fianna Fail voters could be critical.

It seems clear that he is voicing a genuine personal view on the issue, which is a welcome change from the opportunistic and cynical politics of 1983 when the issue was used by Charlie Haughey's Fianna Fail to try to undermine the government. It may also be true that Martin recognizes how Ireland has changed and he does not want to surrender all today's young liberal voters to Varadkar.

But we are only at the beginning of this. It could mean major turmoil in Fianna Fail as it tries to find a way back into power.

At the start of this week Michael McGrath, Fianna Fail spokesman on finance (and likely successor to Martin), said that what is being proposed is "a step too far" and that he could not support unrestricted abortion up to 12 weeks.

How it will all play out in the coming months is impossible to say at this stage. Despite hopes that this time the debate will be respectful and moderate, my bet is that it will become as dirty and divisive as it was back in 1983.

It seems likely that we will quickly get back to angry debates on the most fundamental questions about when life begins, whether abortion is murder, and all the rest of it. A simple claim that it is a woman's right to choose is never going to be enough.

Comments