The skeleton of Charles Byrne, known as the Irish Giant, will not be on display when the Hunterian Museum, named for the 18th-century surgeon and anatomist John Hunter, reopens in March.

Byrne's 'giant' skeleton is the best-known human anatomical specimen in Hunter’s collection at the Hunterian Museum, a spokesperson for the museum told IrishCentral on January 12.

Byrne, who was born in Derry in 1761, had an undiagnosed benign tumour of his pituitary gland, an adenoma, which caused acromegaly and gigantism. He lived with these conditions and grew to be 7’7’’ (2.31m) tall.

In the last years of his life, Byrne made a living exhibiting himself as the ‘Irish Giant.' He died in 1783 at the age of 22 and it has been said that to prevent his body from being seized by anatomists, he wanted to be buried at sea.

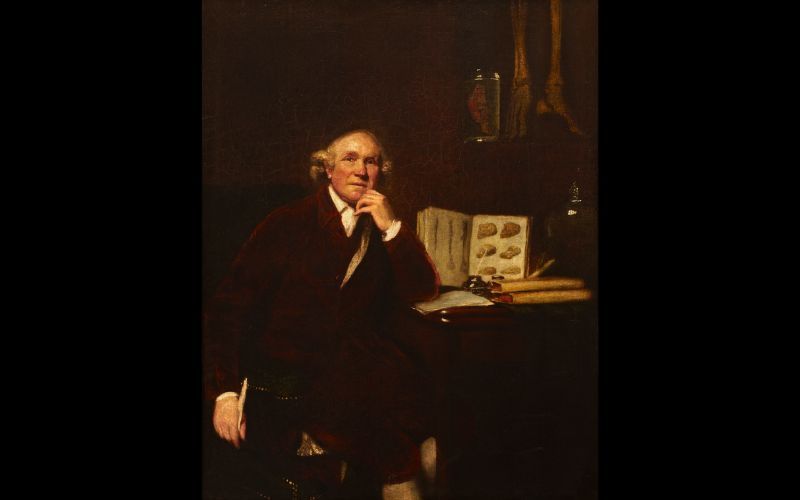

However, Hunter paid Byrne’s friends to hand over Byrne’s body. Three years later, Hunter displayed Byrne’s skeleton in his Leicester Square museum, and part of the skeleton is shown in the background of the portrait of Hunter by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

This portrait will be on public display in the new Museum for the first time in over 200 years.

Portrait of John Hunter (1728-1793) by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), 1785. (Copyright: Hunterian Museum, Royal College of Surgeons of England.)

The Hunterian Museum in London will be reopening in March of this year after a five-year, £4.6 million redevelopment of the Royal College of Surgeons of England’s headquarters at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in central London.

A spokesperson for the Museum told IrishCentral that during the period of closure, the Board of Trustees of the Hunterian Collection discussed the sensitivities and the differing views surrounding the display and retention of Charles Byrne’s skeleton.

The Trustees agreed that Charles Byrne’s skeleton will not be displayed in the redeveloped Hunterian Museum, the spokesperson said, but it will still be available for bona fide medical research into the condition of pituitary acromegaly and gigantism.

In a further statement obtained by CNN, the trustees said: "John Hunter and other anatomists and surgeons of the 18th and 19th centuries acquired many specimens in ways we would not consider ethical today and which are rightly subject to review and discussion."

Campaigners had called on the Hunterian Museum to remove Byrne's skeleton from public display for a number of years.

Byrne's distant relative Brendan Holland, who has the same condition Byrne had, told RTÉ News that he welcomed the news that Byrne's skeleton would no longer be displayed and that it's being kept for medical research.

"It's medical evidence of what someone like myself who is suffering from the condition would have had before I was treated in 1972," Holland said.

Researchers were able to obtain a DNA sample from two of the Byrne's skeleton's teeth, Holland said, which proved the two were related and had the same condition.

"We can’t do anything for dead people but we can help those who are alive and have this condition," Holland told RTÉ News.

"It’s a condition which is particularly prevalent in the area I live in, in east Tyrone and also in south Derry."

Holland noted that the average height for a male around the time Byrne was alive was 5'4 or 5'5, meaning Byrne would have towered over the average male by about two feet.

"He made a lot of money by exhibiting himself," Holland said, "but I doubt if he felt comfortable doing that."

Comments