An international team of astronomers, led by the University of Galway, has discovered the likely site of a new planet in formation, most likely a gas giant planet up to a few times the mass of Jupiter.

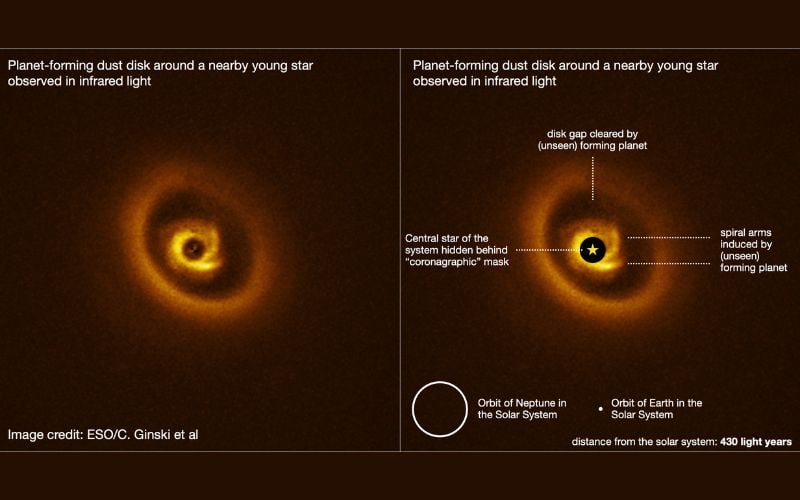

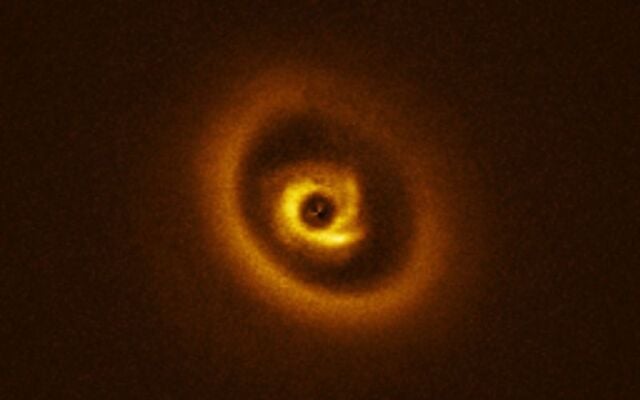

Using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) in Chile, the researchers captured spectacular images around a distant young star for the first time in the form of scattered near-infrared light that revealed an exceptionally structured disk.

The European Southern Observatory (ESO), the world’s foremost international astronomy organisation, has published a stunning view of the new planet-forming disk as its picture of the week.

The disk extends out to 130 astronomical units from its parent star - the equivalent of 130 times the distance between Earth and the Sun. It shows a bright ring followed by a gap centered at roughly 50 astronomical units.

Galway researchers discovered "the disk extends out to 130 astronomical units from its parent star".

For comparison, the outermost planet in our solar system, Neptune, has an orbital distance from the Sun of 30 astronomical units.

Inside the disk gap, reminiscent of the outskirts of a hurricane on Earth, a system of spiral arms is visible. While appearing tiny in the image, the inner part of this planet-forming system measures 40 astronomical units in radius and would swallow all of the planets in our own solar system.

The study was led by Dr. Christian Ginski from the Centre for Astronomy in the School of Natural Sciences at the University of Galway and was co-authored by four postgraduate students at the University.

Read more

Dr. Christian Ginski, lecturer at the School of Natural Sciences, University of Galway and lead author of the paper, said, “While our team has now observed close to 100 possible planet-forming disks around nearby stars, this image is something special.

"One rarely finds a system with both rings and spiral arms in a configuration that almost perfectly fits the predictions of how a forming planet is supposed to shape its parent disk according to theoretical models.

"Detections like this bring us one step closer to understand how planets form in general and how our solar system might have formed in the distant past.”

The study has been published in the international journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Dr. Ginski said, “Besides this exceptionally beautiful planet-forming cradle, there is something else that I find quite special about this study.

"Along with the large international team that we assembled for these observations, four of our own University of Galway graduate students were involved in this study.

"Without the critical help of Chloe Lawlor, Jake Byrne, Dan McLachlan, and Matthew Murphy, we would not have been able to finalise the analysis of these new results. It is my great privilege to work with such talented young researchers.”

The wider research team included colleagues in the UK, Germany, Australia, the USA, the Netherlands, Italy, Chile, France, and Japan.

The scientific paper speculates on the presence of a planet based on its structure and the rings and spirals observed in the disk. It also notes some tentative atmospheric emissions of just such a planet, which the research team says requires further study to confirm.

Based on their research findings, Dr. Ginski and his team have secured time at the world-leading James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observatory in the upcoming observation cycle.

Using the unprecedented sensitivity of the James Webb Telescope, the team hopes to be able to take an actual image of the young planet. If planets in the disk are confirmed, it will become a prime laboratory for the study of planet-disk interaction.

The full study can be read here.

Watch a short video simulation of an exceptionally structured disk formation here:

Comments