This is an extract from “Have Ye No Homes To Go To? The History of the Irish Pub” by Kevin Martin.

Before 1830 the majority of Irish immigrants to North America were Protestant. By 1840, they accounted for a little more than 10 percent. The 1830s and 1840s were the age of mass emigration of Catholics from Ireland to America. Leaving behind a desolate and famine-ravaged country, Irish Catholics arrived in staggering numbers.

Just under four million Irish people immigrated to the United States between 1840 and 1900, and more than 1.7 million of those left Ireland between 1840 and 1860. In each decade between 1820 and 1869, the Irish accounted for over 35 percent of all immigrants to America. From 1841 to 1850, the figure was 46 percent! After 1860, the figure gradually dropped until it was a little more than 2.5 percent in the decade from 1911 to 1920.

Catholic immigrants overwhelmingly settled in urban areas; by 1920, 90 percent of Irish immigrants to the United States lived in cities and towns.

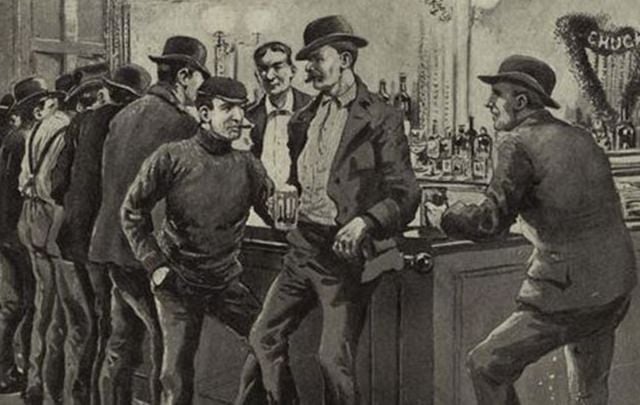

Three-quarters of the Irish immigrants in America lived in seven industrialized urban zones: Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Illinois, Pennsylvania and Ohio. The vast majority of these immigrants ended up in low-paid, low-skilled jobs, but for some, saloon-keeping was viewed as a road to financial success. The image of a saloon in Ireland and England is generally that of a high Victorian-style establishment with ornate decoration and expensive furnishings, typically located in an urban environment.

The Crown Liquor Saloon in Belfast is perhaps the most famous and elaborate example. In America, the term was used to describe a wider range of establishments. The Irish, like other ethnic groups, sought to recreate their social environment in a new context.

The Italians brought their restaurants; the Irish brought their pubs. Some countries brought a cuisine; the Irish brought their alcohol. Emigration is recognized as a stressful process, and psychologists have long noted the propensity of stressed emigrants to revert to native comfort foods.

In America, at that time most business areas were dominated by Protestants. Owning a saloon was a way for an Irish Catholic to gain a foothold in commercial life. The costs of entry were low, and many fine establishments evolved from humble saloons. However, the Irish did not have the pub trade all to themselves. German pubs with beer gardens and elaborate dance floors were popular with the social elites.

At the start of the American Revolution in 1775 there were saloons in Philadelphia called The Faithful Irishman, The Lamb and Three Jolly Irishmen. By 1820, the Southwark part of the city was heavily populated by Irish immigrants, and of the eighty-three liquor licenses in the municipal area, thirty-one of them were held by recognizably Irish names. The situation in nearby Worcester was even more pronounced. By 1880, two-thirds of the applicants for licenses were Irish, even though they accounted for less than a third of the population. While just one-sixth of the city’s population was born in Ireland, half of the saloon keepers were Irish and another 10 percent were Irish American.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

As far back as 1868, Michael ‘King’ McDonald, the so-called ‘Gambler King of Clark Street’ was a powerful politician, saloon keeper and illegal gambling boss in Chicago. While the German beer gardens tended to the prosperous, the quality of Irish saloons was varied.

Richard Lindberg, biographer of Michael McDonald and noted Chicago historian, wrote that they ran the gamut ‘from simple, unpretentious basement dives with dirt floors and wooden planks propped up by barrels to elegantly festooned showplaces like the kind Hal Varnell kept on Randolph Street.’

‘Prince Hal’ was a notorious gambler and political kingmaker who was later appointed warden of the Cook County Insane Asylum. The Chicago Inter-Ocean newspaper carried a report on his saloon, noting that it was ‘fitted up with the most skillful contrivances and appliances for the perpetration of crimes so dark they cannot be named.’

In her PhD thesis ‘Emerald Pub to Silver Saloon: Building an Irish Saloon Community in the American Mining West,’ Michelle A. Charest studied saloon proprietorship in Virginia City, NV in 1870. She found the Irish were the largest group of ethnic saloon keepers, followed by the Germans. Irishmen controlled eighteen saloons – 26 percent of the drinking establishments in the city – while Germans owned fourteen, or 19 percent of the total. However, it was the Germans who were the best represented when total population was taken into account.

In 1899, John Koren studied crime figures in an attempt to see if the widespread vilification of the Irish in America as drunken criminals was statistically valid. The Irish ranked third, behind the Scottish and Canadian ethnic groups, and were on a par with the Polish, English and Americans. He concluded that ‘Irish saloons stand for immoderate drinking and drunkenness in greater measure than any other.’

A stereotype had been created, and any drunken act by an Irish person was an indication of the nation’s propensity for alcohol and criminality, while other ethnic groups with similar statistical profiles were ignored. Koren was an avowed teetotaler but did not envisage damnation for the drinkers. They were not a riotous company intent upon reducing themselves to drunkenness, but ‘a well-behaved group of men who play cards together, read, smoke and drink a glass of beer . . . in not a single one of the many such groups observed did drinking seem to be the most important thing.’

The Five Points area of lower Manhattan was once synonymous with Irish, poverty, violence and alcoholism. In 1835, renowned frontiersman Davy Crockett visited the area. He compared the Irish of his acquaintance in the western states to the Five Pointers: ‘In my part of the country, when you meet an Irishman, you find a first-rate gentleman; but these are worse than savages; they are too mean to swab hell’s kitchen.’

Charles Dickens passed the same way in 1852, and referred to ‘hideous tenements which take their names from robbery and murder; all that is loathsome, drooping and decayed is here’. Jocelyn Green described the area in her 2014 novel "Yankee in Atlanta": ‘If Broadway was Manhattan’s artery, Five Points was its abscess; swollen with people, infected with pestilence, inflamed with vice and crime. Groggeries, brothels and dance halls put private sin on public display. Although the neighborhood seems fairly self-contained, more fortunate New Yorkers were terrified of Five Points erupting, spreading its contagion to the rest of them.’

The area was originally a pond which was filled in by the authorities to build accommodation for the rapidly expanding immigrant population. However, the builders did not take account of the softness of the ground, and the condition of the tenements deteriorated quickly.

The Irish population in New York City rose from 961,719 in 1850 to 1,611,304 by 1860, and the vast majority of these newly arrived citizens were housed in these abysmal tenements. The buildings were often little more than outhouses. In the late nineteenth century, a report on tenement life around the Five Points counted one bathtub for 1,321 families and one water tap for a floor of apartments. It was an area heavily polluted by industry. Businesses using naphtha, benzene and other flammables made fire a daily hazard. The area was notorious for the number of saloons, brothels and groggeries – the majority of them owned by Irish and Germans.

According to Wilson’s Business Directory of New York City, the Sixth Ward had a population of 24,000 in 1860. There were 204 groceries and 169 saloons or porterhouses. The groceries – more commonly referred to as groggeries – were similar to the spirit grocers of the homeland. The New York Clipper – the first newspaper in the United States dedicated entirely to the entertainment industry – described a typical establishment as having ‘a grease-covered counter’ and ‘an inevitable bar’ at the back. Behind the bar, the setup was basic: ‘a score of tall necked bottles . . . a beer barrel stands in the extreme corner, and in these articles we have the most lucrative portion of the grocer’s trade, for no purchaser enters the murky store without indulging in a consolatory drink, be their sex as it may’. Billiard tables and prostitutes were common.

Crowne’s Grocery was the best known. It was, according to one of the local Protestant charitable organizations, ‘the most redoubtable stronghold of wickedness in Five Points if not in New York’, and was memorably described by George Foster in his 1850 book New York by Gas Light: ‘It is not without difficulty we should effect an entrance through the baskets, barrels and boxes, Irish women and sluttish housekeepers, white, black, yellow and brown, thickly crowding the walk right up to the threshold – as if the store were too full of its commodities and customers and some of them had tumbled and rolled outdoors.’

He noted piles of cabbages, potatoes, squashes, eggplants, tomatoes, turnips, eggs, dried apples, chestnuts and beans piled around the floor. Hardware was also in evidence: ‘boxes containing anthracite and charcoal, nails, plug tobacco, etc, etc, which are dealt out in any quantity from a bushel or a dollar to a cent’s worth . . . firewood, seven sticks for sixpence, or a cent apiece, and kindling wood three sticks for two cents.’

He described the casks of molasses, rum, whiskey, brandy and all sorts of cordials. The latter, he said, were ‘carefully manufactured in the back room where a kettle and furnace with all the necessary instruments of spiritual devilment are provided for the purpose’. After describing a myriad of other foodstuffs available, he described the bar: ‘Across one end of the room runs a long, low, black counter armed at either end with bottles of poisoned firewater, doled out at three cents a glass to the loafers and bloated women who frequent the place.’

* Kevin Martin taught English, communications and cultural studies for twenty-five years. He is married with two children and lives near Westport, County Mayo. He loves pubs, travel and reading. This is his first book.

“Have Ye No Homes To Go To? The History of the Irish Pub” is published by The Collins Press and is available from www.collinspress.ie.

* Originally published in Sept 2016, updated in Aug 2023.

Comments