On April 24, 1916, the Irish rebellion known as the Easter Rising began, leading to the destruction of Dublin's city center, major loss of life, and the eventual execution of the cause's leaders. Here's how it all played out.

In honor of the anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, we provide a day-by-day guide to how the rebellion played out.

From its beginnings on Easter Monday on April 24, 1916, the rebellion destroyed the city of Dublin and led to the execution of its leaders after their surrender.

The suppression of the rebellion sparked outrage among Irish citizens over the execution of the Rising's leaders, generated a nationalist surge leading to support for Sinn Féin and its separatist agenda that would lead to the War of Independence, the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty that partitioned Ireland into north and south, and the eventual rejection of the free state's position as a dominion in the British Empire and its establishment as a fully independent republic in 1949.

Some may argue that it also acted as a forerunner to the violence seen during The Troubles in Northern Ireland, with Sinn Féin acting as inheritors of the ideals left behind by the passionate rebellion leaders.

Day One - April 24, 1916

In the days preceding the outbreak of the rebellion, there had been much confusion among the Irish Volunteers. The military action had previously been scheduled to get underway on Easter Sunday until Irish Volunteer leader Eoin MacNeill issued a countermanding order to all volunteers that armed insurrection would not take place.

MacNeill had never believed in the rebellion and had initially been kept in the dark, but on learning what was afoot several months previously, he was convinced to act by the promise of German support and a shipment of German arms that was to be delivered in Kerry by Roger Casement aboard the Aud.

However, when the Aud was intercepted on Good Friday, Casement captured and the shipment of arms lost as the British scuttled the boat, MacNeill ordered Volunteers to stay at home.

Two members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood military council were convinced that the Rising should go ahead and by overruling MacNeill’s order, Thomas Clarke, long thought to be the military mastermind behind the Rising, and socialist leader James Connolly, the founder of the Irish Citizen Army, insisted that the Rising go ahead one day behind schedule on Easter Monday.

Nonetheless, it being 1916 and not having the instant communication abilities we have now, the word about the rescheduled insurrection did not spread far, meaning that the vast majority of Irish Volunteers were still in their homes all around the country when on Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, 1,250 members of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army assembled across Dublin.

Easter Monday, 11:00 am Around 1,250 members of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army, including 200 women from Cumann na mBan, assembled across Dublin.

11:30 am - 12:30 pm: Within the first hour of the rebellion, rebels stormed and occupied several of the capital city’s most important political and economic buildings: Jacob’s factory, the Four Courts, Stephen’s Green, the South Dublin Union (now St. James’s Hospital), Jameson Distillery, the Mendicity Institute, Boland’s Mills and Bakery, plus 25 Northumberland Road and Clanwilliam House.

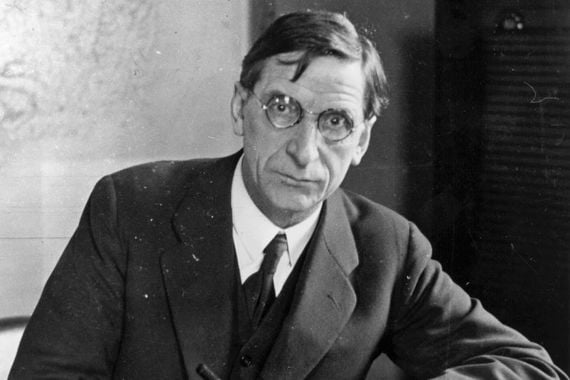

The Volunteers' Dublin division had been divided into four battalions led Proclamation signatories Commandant Thomas MacDonagh and Commandant Éamonn Ceannt; future Irish Taoiseach and President, the New-York born Commandant Éamon de Valera; and Commandant Ned Daly.

The first battalion under Daly made up about 250 men. They occupied the Four Courts, apart from D Company, lead by Seán Heuston, whose 12 men would occupy the Mendicity Institution, across the river from the Four Courts.

The second battalion of 200 men was lead by MacDonagh and assembled in Stephen’s Green with orders to occupy Jacob’s biscuit factory.

De Valera was in charge of the 3rd battalion of 130 men and they would take Boland's Mills.

The fourth battalion, led by Éamonn Ceannt and numbering about 100 men, was to guard against British troops coming from their base in the Curragh Co. Kildare, by taking the South Dublin Union, which was near to the main rail line from the west and southwest.

At Liberty Hall, 400 volunteers under the command of Commandant James Connolly gathered in preparation for the day's action. From there, 100 men and women from the ICA, under Commandant Michael Mallin, were sent to Stephen’s Green just south of Grafton St.

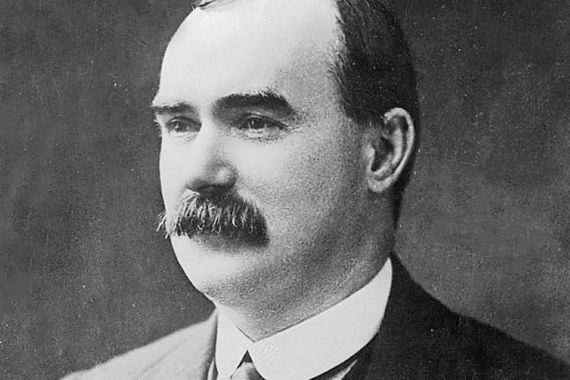

James Connolly.

At 12 pm, rebels attempted to seize weapons from the Magazine Fort in Phoenix Park but, despite disarming the guards, they failed to obtain any arms.

Rebels also failed to take Trinity College Dublin, which was defended by a handful of Unionist students.

Most importantly, however, the General Post Office (GPO) on Sackville Street, Dublin’s main thoroughfare (now known as O’Connell St), was stormed, seized, and established as rebel headquarters. Customers and staff were expelled from the building and a number of British soldiers who were present were taken prisoner.

All remaining men not within the first four battalions were stationed here, including five members of the military council: Pádraig Pearse, President and Commander-in-Chief, Tom Clarke, James Connolly, Seán Mac Diarmada and Joseph Plunkett.

Pádraig Pearse, President and Commander-in-Chief.

At 12:20 pm, the Tricolour was raised above the GPO, along with a green flag bearing the words “Irish Republic” as the rebels settled in for battle.

The forced entry into the buildings was not without incident, however, and it is believed that in Jacob’s and Stephen’s Green rebels shot civilians who attempted to break down their barriers or to attack them. In other stations, instead of shooting civilians, anyone who showed defiance to the rebels was hit with a rifle butt.

The first official fatality of the rebellion was a non-combatant, a nurse attempting to tend to the injured. Margaret Keough, the grand-niece of US Cavalry Captain Myles Keogh, was shot by a British soldier as she responded to shots and attempted to save those injured.

12:45 pm: To a confused gathering of Dublin citizens, bemused by what they were witnessing, Pádraig Pearse emerged from the GPO to decree the independent Irish Republic for the first time, reading aloud the proclamation he himself had written on behalf of the “Provisional Government” of the new Irish Republic.

Inside the GPO in the aftermath of the Easter Rising.

Still applauded as a work of inspiration, the Proclamation of the Irish Republic set all citizens of Ireland on equal terms – men, women, and children – praising the work of Irish emigrants on behalf of the Irish cause, in particular, “her exiled children in America” without whom, some claim, the Rising may never have happened.

To the average Dublin citizen, the storming of the GPO and other buildings by the rebels was not a cause for celebration as they attempted to carry on with their normal lives, unhappy with the unrest and violence brought to their streets.

1:22 pm: On Easter Monday, many British soldiers in Ireland, in particular, those stationed in Dublin Castle, the center of British rule in Ireland, had gone to Fairyhouse racecourse to enjoy the Irish Grand National, leaving the city short of the troops when the Rising began.

The Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in Ireland, General Lovick Friend, was on leave in England, Officer Commanding the Dublin Garrison, Colonel Kennard, could not be located and it was left to his adjutant, Col. H. V. Cowan to call for Marlborough Barracks to investigate the disturbance at the GPO. He also called Portobello Barracks, Richmond Barracks, the Royal Barracks, and the barracks in the Curragh to send reinforcements.

Despite the absence of troops at Dublin Castle, the rebels hesitated to take the building, a move that would have been a significant blow to the British and of vital importance to the rebels. The unit disarmed those in the guardroom and shot a police sentry but failed to press any further as those inside – alerted by the shots – began to close the castle gates. Instead, the small detachment of men allocated to the area under Captain Seán Connolly opted to take City Hall.

Michael Mallin, joined by Countess Markievicz, dug trenches in Stephen’s Green, commandeered passing vehicles in order to make a barrier, took buildings around the park including the Royal College of Surgeons.

The rebel Countess Markievicz.

1:38 pm: At the Four Courts along the Liffey a troop from the 5th and 12th Lancers was ambushed by Daly’s men, who were the first engage with British troops. The troop had been escorting an ammunition convoy along the North Quays when they were forced to take refuge in nearby buildings because of rebel fire.

Attempts were made by the British Army to gain access to the GPO by charging down Sackville St. They were repulsed, however, as they passed Nelson’s Pillar and the rebels opened fire, killing three cavalrymen and two horses and fatally wounding a fourth man.

4:45 pm: On Northumberland Road on the southside of the city, the elderly and unarmed Veteran Defence Force walked into a rebel ambush.

By the end of day one: Just a few hours into the Rising, and despite the poor coordination of the British Army response, the rebels were already losing ground, with those in the eastern end of the South Dublin Union surrendering. The Union complex as a whole remained in rebel hands, however.

Encountering an outpost of Ceannt’s force at the Union, men from the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment (RIR), faced off with rebel’s under Section-Commander John Joyce.

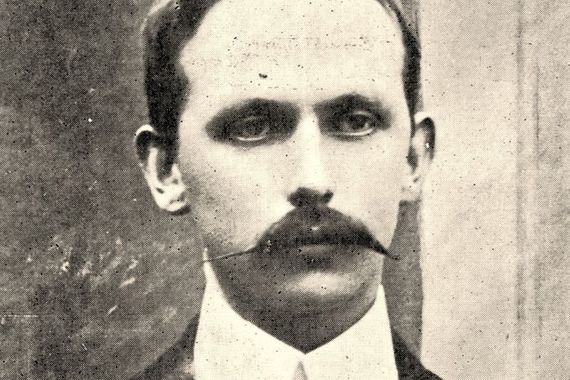

Eamonn Ceannt.

Although they lost three men in the first volley and further men as they were repelled a number of times, eventually the superior numbers of the British Army succeeded and the small rebel force surrendered.

Additionally, on the first day of the Rising three unarmed members of the Dublin Metropolitan Police were shot dead causing their Commissioner to pull the police off the streets. The lack of police presence is blamed for the level of looting that took place throughout the city as buildings were torn apart during the week. In total, 425 people were arrested for looting after the Rising. - Frances Mulraney

Day Two - April 25, 1916

On the second day of the Rising, the Irish rebels fought to hold their positions, news – in addition to misinformation – began to spread throughout Ireland, looting erupted on Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street), British General William Lowe arrived in Dublin to assume control of the British forces in Dublin, and Lord Lieutenant at the time, Lord Wimborne, declared martial law. While until this point the Irish Volunteers had seen relatively little confrontation from British forces, by the end of the second day of the Rising, almost 7,000 additional British soldiers had moved into Dublin from the Curragh in Co. Kildare and from Belfast.

In fact, until this point, some of the rebel strongholds encountered the most resistance from disgruntled civilians. According to the testimony of a 15-year-old named Martin Walton, who joined the Volunteer Forces at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory, “When I arrived then at Jacob’s the place was surrounded by a howling mob roaring at the Volunteers inside, ‘Come out to France and fight, you lot of so-and-so slackers’. And then I remember the first blood I ever saw shed. There was a big, very, very big tall woman with something very heavy in her hand and she came across and lifted up her hand to make a bang at me. One of the Volunteers upstairs saw this and fired and I just remember seeing her face and head disappear as she went down like a sack. That was my baptism of fire, and I remember my knees nearly going out from under me. I would have sold my mother and father and the Pope just to get out of that bloody place.”

5:30 am: After sustaining gunfire from the roof of the Shelbourne Hotel, the rebels at St. Stephen’s green retreat towards the Royal College of Surgeons.

The Shelbourne Hotel today.

Mid-day: Irish rebel forces lose control of City Hall. As Debra Kelly recalled for IrishCentral, venerable actress and gunrunner Helena Molony was among the small group who tried to hold on to City Hall, even as British troops flooded in.

“As British troops advanced on the tenuous stronghold, and the mostly unarmed group surrendered, the prisoners were dealt with amidst the assumption that the women were only present as nurses and medical support, not as the front-line combatants that they were.” However, once the truth was revealed, Molony and her fellow female fighters were taken to Kilmainham with the rest of those captured.

4:10 pm: Rebels at the GPO witness looting all along Sackville (now O’Connell) Street.

Evening: In response to the reports of looting, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington went to the city center to attempt to organize a civilian police force. However, he was arrested at Portobello Bridge by members of the 11th East Surrey Regiment and fell into the hands of one of the Rising’s most notoriously vengeful British officers, Captain J.C. Bowen-Colthurst. Sheehy-Skeffington was then held hostage by an army raiding party and, per Bowen-Colthurst’s orders, executed the following day along with two pro-British journalists who had the misfortune to be in a shop the troop raided.

9:40 pm: Martial law declared in Dublin by the British. - Sheila Langan

Day Three - April 26, 1916

On the third day of the rebellion, the tide began to turn. From 8 am, the gunboat Helga began shelling Liberty Hall. At the Mendicity Institute, near the Four Courts, the rebels surrender after ammunition finally runs out.

For civilians conditions were deteriorating – the air was filled with smoke, food was running low and danger and possible death were everywhere.

British reinforcements arrive in Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) and are welcomed by Dubliners, some giving them food before they march toward the city. Many of the British soldiers were confused thinking they had been en route to France. Also many were inexperienced, some having only learned to operate their weapons on the docks.

The Battle at Mount Street Bridge is something of a small victory for the Irish rebels as the British army suffered their highest casualties of Easter Week. Sackville Street continues to suffer heavy bombardment and fires break out.

By the end of the third day, General Sir John Grenfell Maxwell was dispatched from London to deal with the Rising. After “Martial Law” had been declared the previous day General Maxwell was to be judge and jury in Ireland upon his arrival.

6:20 am - British reinforcements arrive by ship in Kingstown Harbour (now Dún Laoghaire). Many of the British soldiers were apparently confused as to why they are in Ireland and not France. The local Dubliners greeted the soldiers cordially, some bringing them food.

8:00 am - Liberty Hall is shelled by the British. By midday, the building, which spawned the insurrection, is pulverized by artillery fire.

9:00 am - Jacob’s biscuit factory is under heavy machine-gun fire from Dublin Castle. It is reported that many civilians are killed by the automatic fire as they venture out seeking food, which is running low, or to check on friends and relatives. Others are killed in their homes.

British troops in the Gresham Hotel, on Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street), and Volunteers in the GPO engage in a gun battle for hours.

11:00 am – At Stephen’s Green one of the most peculiar scenes of the Rising is witnessed – a brief ceasefire allows the caretaker to feed the ducks. The caretaker leaves his lodge, near Earlsfort Terrace, and walks to the duck pond. Both sides cease fire and are transfixed by his actions.

However, this peace did not last. James Stephens took a walk to Stephen’s Green that morning. Rebels sniped from the roof of the Royal College of Surgeons and machine guns were positioned on the roofs of Shelbourne Hotel, the United Service Club, and the Alexandra Club.

Stephens wrote, “Through the railings of the Green some rifles and bandoliers could be seen lying on the ground, and also the deserted trenches and snipers’ holes.”

“Small boys bolted in to see these sights and bolted out again with bullets quickening their feet. Small boys do not believe that people will really kill them, but small boys were killed.”

Meanwhile Sackville Street has turned into a warzone. From the river, machine guns are firing and incendiary bullets have caused the remaining shops and canopies to set fire.

12:40 pm – Rebels disperse between 25 Northumberland Road, the road’s schools, and Clanwilliam House. Four battalions of the Sherwood Foresters Regiment arrive and are ambushed.

General William Lowe had ordered that the bridge at Mount Street be taken “at all costs” and the troops continued to attempt to take the bridge. By the end of the third day, the rebels had killed 240 soldiers, two-thirds of the British losses for Easter week.

1:45 pm – The Dublin Fusiliers, the Irish infantry Regiment of the British Army, capture the Mendicity Institute (on Usher’s Island) and lay siege to the Four Courts, on the River Liffey.

2:00 pm - The British set up a heavy machine gun position in Purcell’s Shop at the tip of Westmoreland Street’s junction with D’Olier Street and fire up Sackville Street.

3:50 pm - Marrowbone Lane Distillery (Jamesons’) is under constant sniper fire from the Rialto direction.

4:00 pm - The attack on the Four Courts by riflemen from the south continues. The Linenhall Barack, to the north, has been set alight and the air is filled with smoke.

5:00 pm – On Northumberland Road, a ceasefire allows doctors and nurses from Sir Patrick Dunne’s hospital to enter into the kill zone. Fighting continues on Mount Street Bridge.

Shots continue to ring out on Sackville Street and the fire is increasing.

6:00 pm – 25 Northumberland Road, held by rebels, is taken. The door was blown off and the British troops were met with a sea of fire.

6:15 pm – At Church Street Bridge, by the Four Courts, two rebels undertook an act of suicidal bravery by rushing across the bridge setting fires and rushing back. The British troops retreat from the southern quays.

6:30 pm – The Sherwood Foresters gain ground taking a second position on Northumberland Road, captured at the rear of the Parochial Hall.

6:40 pm – Liberty Hall is now destroyed. It is stormed by infantry who find it empty.

7:00 pm – The British continue to gain ground in a bloody battle at Mount Street.

Clanwilliam House is shot to pieces by machine guns on Haddington Road.

8:00 pm - Mount Street Bridge is in British hands and they have entered Clanwilliam House’s outer walls.

8:30 pm - Clanwilliam House has fallen.

10:00 pm - Boland’s Mill is under constant attack.

Thomas Walsh wrote about being inside the Mill. He said, “During the latter fight Paddy Doyle would say, ‘Boys, isn’t this a great day for Ireland?’ and little sentences like this. He was very proud to live to see such a day.

“After some time Paddy was not saying anything. Jim spoke to him and got no reply. He pulled him by the coat, and he fell over into his arms. He was shot through the head.”

On Sackville Street, silence descended while snipers wait for any movement. - Kate Hickey

Day Four - April 27, 1916

The Volunteers lose some crucial areas in Dublin on the Thursday of the Rising with constant heavy fire raining down on headquarters at the GPO. The Four Courts is experiencing heavy fire from machine guns. Capel St is taken by the British, but, despite numerous attacks, increasingly dangerous conditions in the GPO, and a bad injury sustained by James Connolly, the Volunteers remain strong in defense of the building.

8:40 am: Working overnight, the British had established “slit trenches” (or “defensive fighting positions” as they’re more commonly known) within Fairbrother’s Field to the back of the South Dublin Union, allowing British troops to open fire on Marrowbone Lane Distillery.

Despite their many attempts to take the building, the South Dublin Union continues to be a thorn in the side of the British as they struggle to bring down the Rising.

10:00 am: Rebel troops begin to reorganize with men and guns sent to those who are struggling to maintain control of their operational centers. The Volunteers in Westland Row train station are hard-pressed and, so, a sortie of rebels on bicycles speeds away from Jacob’s factory in the direction of St. Stephen’s Green to help out.

10:35 am: Despite several advances, the British fail to take Marlborough Lane Distillery with homemade bombs being flung by rebels whenever troops reach the outer wall.

Those making their way on bikes to Westland Row encounter the Staffordshire battalions positioned around Merrion Square. Unable to break through, the supporting rebels retreat to Jacob’s leaving those in the train station to fend for themselves.

As they cycle back by Stephen’s Green on the way to the factory, a machine gun opens fire bringing down one of the cyclists. The other Volunteers stop to shoot back and are assisted by those holding the nearby Royal College of Surgeons.

11:35 am: The British attack continues and wave after wave of bullets strike the buildings still controlled by the rebels. Sackville St is pounded with artillery as the British try to bring down headquarters in the GPO. They succeed in capturing Capel Street Bridge and also attack the Four Courts, North King Street, and the South Dublin Union in an attempt to blast through a passageway for troops in a bid to provide access for an assault on the GPO.

Four Courts, North King Street.

At South Dublin Union second-in-command Cathal Brugha is badly injured. Not able to retreat from the Union when the order was given, Brugha was thought to be lost but, although still surrounded by enemy soldiers, he was found by Eamonn Ceannt singing “God Save Ireland” with his pistol still in his hand and brought to safety.

He would go on to fight in the War of Independence and in the Civil War, taking the anti-Treaty side. He would be killed during the Civil War despite his reluctance to take up arms against the pro-Treaty side, refusing to surrender after forcing his men to do so in 1922 when a severe bullet wound severed an artery in his leg. He died on July 7, 1922.

With the GPO coming under sustained fire, a nearby warehouse owned by the Irish Times was hit several times, eventually causing a fire that spread throughout the day.

1:15 pm: The British appear to be planning something large at the Four Courts with sniper fire raining down from the roof of Jervis Street Hospital. Shellfire is increasing and the noise is deafening.

3:02 pm: There are huge casualties reported on Sackville Street as a further assault by infantrymen is repelled just a short time after another failed attempt on Abbey St. Everything between Lower Abbey Street and Eden Quay is ablaze with rebels taking down any British who attempt to escape through a burning barricade. The infantrymen were left with only two choices: be shot by rebels trying to escape the blaze or take their chances in the fire.

4:35 pm: The South Dublin Union is still holding out despite machine-gun fire from the Royal Hospital and troops from the Sherwood Foresters’ and Royal Irish regiments going to ground to engage in close-quarter combat.

4:42 pm: Things are not looking so good for the rebels around Capel St and on Capel St Bridge as their forces are cut in two by the Sherwood Foresters. Wanting to ensure they can completely secure the area, the infantrymen are removing civilians from their homes.

8:00 pm: Capel St is taken and secured by the British. This is extremely problematic for the rebels on the north side of the River Liffey as the British troops at Capel St can now act as a blockade between headquarters in the GPO and those Volunteers still fighting in the Four Courts.

8:25 pm: It is at this time that rebel leader and Proclamation signatory James Connolly is first injured. Wounded in the fray on Middle Abbey St, he is brought back to the GPO where he is treated by a captured British Army doctor.

Connolly had first been injured by a gunshot to the shoulder outside the GPO and he sought first aid from a medic without drawing attention to his injury. Later, however, he took another bullet to the left ankle which left him unable to walk or stand. Although treated by a doctor he would spend the rest of the Rising on a makeshift stretcher unable to walk with the wound growing gangrenous through lack of proper treatment.

11:00 pm: On the opposite side of Sackville St., Hoyte’s Druggist and Oil Works have suffered heavy damage due to fire from British boat “The Helga” on the Liffey. The Oil Works explode in a ball of flames scattering debris over a wide area.

11:30 pm: By the end of day four, with the continued bombardment from the British, rebels on O’Connell Bridge, south of the GPO on Sackville St, and those along Henry St., which runs just to the north of the building, begin to retreat to the rebel headquarters.

Things in the GPO were getting increasingly desperate. Small fires were breaking out on the roof and in the surrounding buildings while the rebels attempted to put out any they could. Between the buildings around the GPO, the Irish Times Warehouse, and the Oil Works, Dublin glowed red with fire by the time night fell.

Thankfully, changes in wind speed and direction offer some respite for the rebels. Across the street at Clery’s and the Imperial Hotel, however, such was the heat created from the burning interiors of the buildings that molten glass is now raining down on Sackville St.

Machine guns will continue to fire throughout the night. At the end of Thursday, James Connolly lies propped up on a mattress still trying to mastermind the Volunteers' defense. All members of the Provisional Government are now gathered at headquarters. - Frances Mulraney

Day Five - April 28, 1916

On day 5 of the Rising, the Volunteers are forced to abandon their headquarters in the GPO as conditions within the building became too dangerous. In other parts of the city, they hold onto Boland’s Mills bakery, the Royal College of Surgeons, Jacob’s Biscuit Factory, the South Dublin Union, and the Four Courts.

7:55 am: It’s been a long and brutal night for the Volunteers with no let-up from British troops attacking Sackville St. The area is unrecognizable with human and animal corpses littering the street. The surrounding buildings are descending into piles of rubble.

10:00 am: Tension among the forces is mounting with a massacre of captured insurgents and civilians narrowly avoided with thanks to the last-minute call from a British major. They are instead sent to the Custom House.

The Custom House today.

The college located on Bolton Street is thronged with refugees trying to escape the burning city.

11:00 am: There is a respite taken by the Volunteers at Marrowbone Lane Distillery when they spot enemy soldiers burying their dead in shallow graves.

The Citizen Army located in Stephen’s Green is not only suffering from the threat of bullets but also from intense hunger, with snipers lying in waiting to shoot at the first sign of movement, which cuts off any potential food supply.

The ducks of the park, however, are still well-fed with the park keeper returning several times to ensure their welfare.

Although Boland’s Mills, the Royal College of Surgeons, Jacob’s, the South Dublin Union, and the Four Courts are holding out, the intense pressure placed on the GPO by British troops is taking its toll – and there's no sign of any let-up.

The tension is rising in Boland’s Mills as well. The previous evening, a Volunteer fell to friendly fire, the result of the over-strained senses of an exhausted comrade.

12:00 pm: The Volunteers succeed in preventing a detachment from the 2/6th Sherwood Foresters Regiment from reaching the GPO. Lying in wait on Henry St until they are in close range, they ambush the detachment, and the infantrymen retreat.

2:00 pm: Another successful ambush by the Volunteers, this time near Bolton Street on the south side of the city.

That morning the 2/6th South Staffordshires had moved to their Bolton Street headquarters from where they began to launch an attack on North King Street. As they marched, however, the rifle fire began and the soldiers are forced to scramble through the side streets back to Bolton Street.

2:45 pm: Casualties are suffered on both sides as Volunteers stationed on North Brunswick Street and Upper Church Street at Moore’s Coachworks and Clarke’s Diary are involved in a heavy sniper battle with the British soldiers.

3:00 pm: British forces on North King Street have not yet given up and continue to fight inch for inch to reach the Volunteers based at Langan’s Pub. Fire from the Volunteers does not let up, even as the British begin to once again retreat.

Reilly’s pub, instead, becomes the main target for the British. Charging, retreating, regrouping, and charging once more, the British continuously fail to break through with rifle fire coming at them from all directions.

Taking to the rooftops to try and outflank the Volunteer position at Langan’s Pub, the South Staffordshires leave themselves open to rebel fire from the Four Courts and Monk’s Bakery. Once again they are forced to retreat with increasing frustration and ever-growing hatred for the Volunteers.

In Father Mathew Hall, wounded from both sides lie shoulder to shoulder as they are treated by rebel nurses, any differences between them long forgotten.

3:30 pm: On the Northside, the British continue to build barricades that will cut the rebels off. They are now concentrating on a barricade on Moore Street.

The British are adapting to the street fighting being used by the rebels and learning that barricades are the best way to combat it.

4:00 pm: Volunteers in the Four Courts are also holding strong with more guns and ammunition than they had on Easter Monday. Reinforcements from the Four Courts are making their way to Reilly’s Fort.

5:00 pm: The ferocious fighting is still ongoing on North King Street with all rebel fire directed at an armored truck as it attempts to bring in further infantrymen. When the door of the truck is kicked open and a British soldier attempts to jump out, he is shot dead before his foot could touch the ground.

Civilians in this area are left hiding in their homes with no means of escape from the deafening noise and danger.

6:30 pm: The roof of the GPO is caving in, but Volunteers still shoot from amid the building debris.

7:00 pm: As the armored truck on North King Street continues to battle through the fire to bring in infantrymen, it suddenly stops. The driver and co-driver have been badly wounded.

7:30 pm: Plans to evacuate the GPO are developed as the ceiling continues to cave in around the Volunteers' heads. A group of Volunteers leaves the building to establish which escape route to Moore Street would be best.

8:00 pm: The Volunteers based at the Metropole Hotel retreat to a GPO that is now in complete chaos.

Not long after Volunteers abandon the Metropole, the whole hotel collapses.

8:30 pm: The GPO is being given up as a lost cause and after a rousing speech from Pearse, Volunteers sprint desperately in small groups of two or three into Henry Street but apparently the way is barred by machine guns and Volunteers are at a loss as to where to go for shelter.

Volunteer captains McLoughlin and Michael Collins attempt to set up a position on a building named The White House on Moore Street in an attempt to neutralize the British soldiers at the Rotunda hospital.

Michael Collins.

They succeed in placing a truck alongside an existing barricade to shelter themselves from the hospital and proceed to break into civilian buildings on Moore Street, making their way down the street building by building.

A temporary HQ is established in Cogan’s Shop, at the junction of Henry Place and Moore Street, and a barricade is built along the laneway outside.

9:50 pm: The GPO is lost. Pearse is the last to leave the building with Connolly having been carried out earlier on a stretcher.

Moore Street is now a battlefield.

At Cogan’s a new Commandant is appointed - 20-year-old Seán McLoughlin. Connolly is too badly injured, Pearse and Plunket are exhausted and the remaining members of the emergency council of war do not have the military mind. This young man is the only person left they feel they can place their faith in.

11:30 pm: Headquarters is relocated to 16 Moore Street while stalemate reigns over the other locations around the city. - Frances Mulraney.

Day Six - April 29, 1916

On Saturday, April 29, 1916, at 12 pm, rebel headquarters on Moore St surrender. Pearse issues the order to the Volunteers across the city but it is Sunday afternoon before all rebels have laid down arms.

6:30 am: Dublin awakes to a quieter city than it has seen in days with rebels laying low on Moore St. Plans are being put in place to divert the attention of British troops so as to allow the majority of the Volunteers to escape to the Four Courts, a rebel garrison that has been faring much better than their Sackville St counterparts.

Morale in Moore St is low, however, and Volunteers are just simply exhausted after the fight for the GPO. The new Commandant McLoughlin had earlier suggested a do-or-die assault on a British barricade blocking their route to the Four Courts but some of the men are in no position to launch such an attack.

North King Street is still a complete war zone and every inch of space is being fought for. Langan’s pub has now been abandoned by the Volunteers and the street is full of the bodies of those shot down as they attempted to escape. Reilly’s pub is still holding but is under increasing pressure.

Volunteers in the College of Surgeons and Stephen’s Green are not under as much immense pressure as those in Moore St but are starving. Groups are sent out from the college to attempt to search for food but return with slim pickings.

Conditions are much better in the South Dublin Union and a nearby distillery although the quiet that has descended on the city is disconcerting for those on the south side who have no idea how Volunteers on the northside are faring. Those in the Union are well-rested and well-fed and the rebels in the distillery are even planning celebrations of their success for the following evening, unaware that by that time the surrender order would reach them.

8:00 am: Due to exhaustion and frustration on both sides of the fight, several civilians are accidentally killed on Saturday morning while trying to move to safety. Even shadows are immediately shot at with questions asked later as to who exactly they are.

9:00 am: The cycle of British attack and retreat seems endless on North King St and wounded men on the street can no longer be tended to. They are not even in reach of the brave firemen, who have families on both sides of the divide and who have tended to the streets for the past number of days.

Father Mathew Hall, where the wounded are being tended, is packed with the injured, and medical staff struggle to cope with a large number of patients.

10.00: The battle on North King Street seems to finally be coming to an end. The Volunteers decide to leave Reilly’s and tricking the British into thinking they are about to flood out the front door, they jump through the side windows and escape relatively unharmed.

12.00: A white flag emerges from 16 Moore St. The military council appears to have abandoned any hopes of breaking through the barricade to the Four Courts. Nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell emerges from rebel HQ and approaches the British barricade.

Fighting continues through the city, Volunteers unaware that the Rising is nearing an end.

2:30 pm: Surrender negotiations are now underway on Moore St with O’Farrell emerging again from Moore St, accompanied this time by Pádraig Pearse. They meet with Brigadier General Lowe to discuss terms.

3:30 pm: The surrender is official. Pearse is driven away by the British and it is O’Farrell who returns to headquarters to issue orders. Connolly is gravely injured and again has to be stretchered from HQ to meet the British.

7:00 pm: As word of the surrender order makes its way to Volunteer positions, those in the Four Courts are stunned. When Commandant Daly initially delivers the order they refuse but eventually reluctantly comply.

The Volunteers on North Brunswick St have not yet been reached but a ceasefire is apparently worked out with the help of two priests and fighting stops there also.

7:45 pm: Volunteers leave Moore St in silence, walking to Sackville St to surrender their weapons. They are detained on the grounds of the Rotunda Hospital. The odd gunshot still rings out across the city.

Day 7 - April 30, 1916

The order to surrender will finally reach De Valera at Boland’s Mill and those on Stephen’s Green and in Jacob’s factory by 10 am on Sunday, April 30.

Eamonn De Valera.

De Valera, however, decides that he does not take orders from a prisoner and with Pearse now in captivity, he now takes orders from Commandant MacDonagh. MacDonagh also states that the surrender order is invalid as Pearse is a prisoner although he agrees to meet with General Lowe to parley.

Although those on North Brunswick had agreed to a ceasefire yesterday, they would not yet believe that a surrender warrant had been issued. Two priests are allowed access to Pearse in order to acquire an official surrender statement.

MacDonagh meets with Lowe and a further surrender deal is reached with a truce in place until 3 pm.

An exhausted O’Farrell is now traveling around the city conveying MacDonagh’s new surrender order to the Volunteers. Some are angry with the order believing they should fight until the end.

The Irish Citizen Army at Stephen’s Green surrender around midday and 120 men and women march from the Green. At 3.30, Jacob’s Garrison also marches into the custody of the enemy.

It wouldn’t be until after 3 pm that the Volunteers in the South Dublin Union would also lay down their arms. Although they comply with the order, they are unhappy and unable to understand why the fight does not continue.

From 4:30 pm, the Volunteers within the grounds of the Rotunda are marched to Inchicore, and with Dublin citizens now emerging from their shelter to view the destruction of the city, the rebels are heckled as they make their way there. The opposite occurs as Vice-Commandant O’Connor leads the 3rd Battalion from Boland’s Bakery. Crowds cheer and offer their support for the rebels.

By 6 pm, the fighting has ended.

There were are least 485 deaths, 50 percent of whom were civilians. In total, 1,350 people lie dead or wounded and 3,430 men and 79 women have been arrested by the British.

Although initially angry at the rebels and their leaders for the week of heavy fighting and the civilian deaths, between May 3 and May 12, 15 of the Rising’s leaders would be executed in Kilmainham Gaol, including all seven signatories of the proclamation, and public opinion regarding the Rising would begin to soften.

Those executed at Kilmainham included Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, Thomas J. Clarke, Joseph Plunkett, William Pearse, Edward Daly, Michael O'Hanrahan, John MacBride, Eamonn Ceannt, Michael Mallin, Sean Heuston, Conn Colbert, James Connolly, and Sean MacDiarmada.

Kilmainham Gaol.

The British had to tie the severely injured Connolly to a chair in order to shoot him.

The most prominent leaders to survive was Eamon de Valera, with thanks to his American birth, and Countess Markievicz, with thanks to her gender.

Sir Roger Casement was later executed in London, following his high-profile trial in which he was charged with high treason.

The other imprisoned men were sent to internment camps in England and in Wales and it was within these camps that the new leaders of the movement would begin to emerge, Michael Collins among them. The camps became known as “Universities of the Revolution”.

By the time of the general election in 1918, the republican feeling is swaying the public away from the more moderate Irish Parliamentary Party and the belief that Home Rule will ever be delivered has all but run out.

The election is a landslide victory for the more radical Sinn Féin, who are mistakenly associated with the Rising, despite them technically having no official part in its planning.

The War of Independence is just beginning.

H/T The Irish Times, Today in Irish History

* Originally published in 2016, updated in April 2025.

Comments