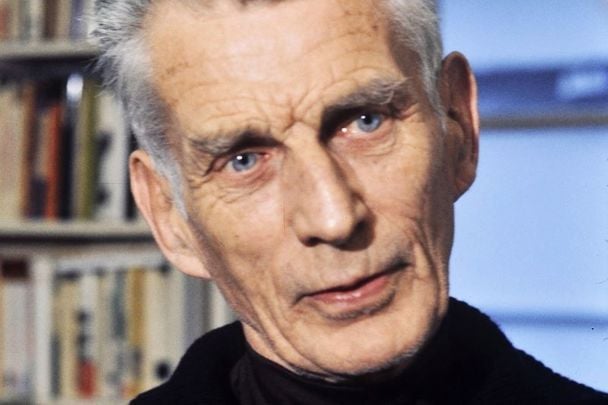

On October 23, 1969, Samuel Beckett received the Nobel Prize in Literature, an accolade that solidified his reputation as one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. IrishCentral revisits the Dubliner's spare, rebellious voice and the works that reshaped theatre and modern storytelling.

We tend not to view Beckett (1906-1989) as a nationalistic writer, but the strife of his youth certainly marked him. I was reminded of this when Beckett scholar Michael Coffey contacted me about the Beckett-Noel Lemass connection.

Noel Lemass was the older brother of future Irish Taoiseach Seán Lemass. He was in the GPO in 1916, fought in the War of Independence, where he held the rank of captain in the IRA, and, like his more famous brother, went against the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. After the end of the Irish Civil War, he was abducted by pro-Treaty forces and brutally murdered, his remains being found months later in the Dublin Mountains.

Lemass’ murder is still controversial to this day, and the perpetrators were never apprehended. Recently, Tim Pat Coogan, in his book on Michael Collins' assassination Squad, The Twelve Apostles, sought to set the record straight. “It was never established exactly who was responsible for the torture and killing of Lemass, but David Neligan himself told me it was the ‘Tobin bunch.’ ” David Neligan was famously Collins’ “Spy in the Castle” and Liam Tobin was Collins’ Deputy Director of Intelligence, running the operation out of #3 Crow Street.

If anyone might know who committed this dastardly act, it is probably Dave Neligan. Coogan speculates that the motive for the murder might have gone back to Collins himself, although he had died the year before Lemass’ abduction. “Noel Lemass,” wrote Coogan, “had been a gifted intelligence officer with the Anti-Treaty Dublin Brigade IRA; he had been suspected of intercepting correspondence between Michael Collins and his fiancée Kitty Kiernan. To some Collins devotees, this alone might have seemed grounds for execution in the fervid political atmosphere of the day.”

Lemass appears in Beckett’s 'Mercier and Camier'

Beckett wrote about Lemass, though not by his exact name, in his novel, 'Mercier and Camier', when his characters come across the Noel Lemass Memorial in the Dublin Mountains:

What is that cross? Said Camier.

There they go again.

Planted in the bog, not far from the road, but too far for the inscription to be visible, a plain cross stood.

I once knew, said Mercier, but no longer.

I too once knew, said Camier, I’m almost sure.

But he was not quite sure.

It was the grave of a nationalist, brought here in the night by the enemy and executed, or perhaps only the corpse brought here, to be dumped. He was buried long after, with minimal formality. His name was Masse, perhaps Massey. No great store was set by him now, in patriotic circles. It was true he had done little for the cause. But he still had this monument. All that, and no doubt much more, Mercier and perhaps Camier had once known, and all forgotten.

I asked Coffey when and where he first discovered Beckett’s interest in Lemass. “I believe it was at a Beckett conference in Phoenix,” he told me. “A scholar named Rodney Sharkey gave a paper on Ernie O’Malley and Beckett, in the course of which he talked about the murder of Noel and the memorial to him in the Dublin hills, which is the subject of some discussion in Beckett’s novel 'Mercier and Camier.'

"Today, there is considerable ‘historicizing’ of Beckett’s work, meaning placing it in the there and then of his time, rather than leaving him afloat as some timeless poet of existential angst.

"It is clear from the novel that Beckett was very moved by the brutal death of Lemass at the hands of the Free State army. And as Mercier and Camier talk about it, Beckett renders them vague about the historic past, a bit of an indictment in this book, written in French in 1946, of the brutal way Irish independence was managed and how much of it was conveniently forgotten. Beckett paid close attention to the conflicts around him, be it Ireland, Nazi Germany, occupied France, Algeria, the Soviet crackdown on Czechoslovakia and Poland in the 1980s.”

Beckett’s formative years were in the wild west town of Dublin, where rival intelligence agents shot each other down in the streets in broad daylight. What effect did this have on Beckett? “This is a region of Beckett studies that is being freshly turned,” maintains Coffey, “his time as a young fellow growing up during the revolution, in Dublin, his folks part of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy feeling the flames, and then later, as a star student at Trinity reading foreign languages but with a rebel’s heart, trying to make sense of the subsequent civil war, and of course the violence to such men as Lemass at the hands of the Civil Guard. Much has been written of late about hunger and starvation in Irish history, from the Famine to the blanket in 1981. Beckett’s Malone, in 'Malone Dies,' wonders how long he can survive on his diminishing servings of soup. Malone recalls ‘Lord Mayor of Cork’—Terence MacSwiney of course—who ‘lasted for ages,’ and it gives him a little hope.”

Many of Ireland’s great writers are viewed as nationalists—Joyce talking about the fall of Parnell in "Portrait of the Artist" and Yeats memorializing the rebel leadership in “Easter 1916”—but Beckett is not viewed in the same manner.

Was Beckett a nationalist writer?

“No doubt, but with qualifications,” said Coffey. “It is not wrong to say he was radicalized to the nationalist cause by his friend and mentor Tom MacGreevy—poet, director of the National Gallery—who introduced the young Beckett to Joyce and to Paris. But Beckett, from the start, despised any nationalist-based aesthetic. But his heart, I like to think, is with whoever fights for self-determination and a condition in which the State cannot dictate what is said or felt—or written. Although he was cool to the excessive nationalism practiced by Yeats, the myth of an ancient Ireland that was to be revived, he cherished many Yeats verses all his life and could recite them to the end.”

"Samuel Beckett Is Closed" takes two and hits to the right

Coffey is the author of a new book called "Samuel Beckett Is Closed." It is such an odd title. I asked Coffey what it meant, and I got an excellent answer worthy of Beckett himself. “Well,” Coffey said sheepishly, “it is a bit of a toss, in that it was inspired by a photo of a traffic sign in Dublin indicating that the Beckett Bridge over the Liffey was closed. But I quickly made the connection to my understanding of Beckett's late work and how it explores narrowing, more closed spaces, as the language begins to undergo a reduction rather than an opening. But Beckett is never really closed. As the vibrant world of Beckett scholarship shows, there are many ways into and through Beckett; he was that kind of artist.”

"Samuel Beckett Is Closed" will delight Beckett fans because, well, it’s so Beckettian. Is it fiction, nonfiction, memoir, or what? “My book is a fiction using real texts,” said Coffey. “Text and kinds of narrative serve as characters, in some sense, so there are elements that are memoir, fiction, literary criticism, baseball play-by-play and appropriated texts about torture, being tortured, justifying torture. I braid them together according to a system that Beckett attempted for a short work, but then abandoned, and that itself becomes a strand in the book’s weave.

Beckett himself makes an appearance in "Samuel Beckett Is Closed" at a twi-night doubleheader played at Shea Stadium on July 31, 1964. Beckett actually attended this twin-bill and it is recounted by his editor and friend Richard Seaver in his wonderful publishing memoir, "The Tender Hour of Twilight."

Says Coffey, “Beckett was in New York—in America—once in his life, for about a month, in 1964. Barney Rosset, Beckett’s American publisher, was eager to produce a film based on a Beckett screenplay. Buster Keaton got the part. It was first class all the way. Boris Kaufman was the cinematographer—I mean, "On the Waterfront," just for starters. It was a very hot month in New York. Beckett came to admire Keaton’s professionalism. It’s a very Beckettian movie, entirely silent but for a ‘Sshhh!’ at the very start. Beckett and Dick Seaver went to the ball games a Friday toward the end of Beckett’s stay. They enjoyed themselves.”

Baseball is famously a game of failure. Of course, the ultimate failure of life is one of the major themes of Beckett’s works so, naturally, he quickly became enamored with the terrible Mets. “I think the failure and the futile pace of things might have been alluring to Beckett,” speculates Coffey. “He was an avid sportsman, let’s not forget. He played cricket at boarding school and at Trinity, I believe, was a tennis player and a good golfer. But an easy day at the ballpark—watching the two worst teams at the time, each of them only three years old, the Mets and the Colt ’45s [now the Astros], must have intrigued him. They stayed for both games.”

Coffey went on to say he “was drawn to using the baseball game one day when I was out walking and thinking about how to mix these many narratives I had, and, following Beckett’s scheme in that abandoned work I mentioned, there were nine themes. I was looking for subtle ways to anchor a reader in a nine-part narrative that in each part went four different directions—having one part be the obvious progression of a baseball game from innings one through nine, with two chaps having a talk about it, inning by inning, seemed a natural fit.”

Read more

Beckett in the age of terrorism

Terrorism—GITMO, the Paris Attacks, 9/11—plays an important part in "Samuel Beckett Is Closed." I asked Coffey why he went down that path and how it is connected to Beckett. “Beckett’s work,” Coffey opines, “however humorous, baffling, or austere, can also be severely discomfiting, from the awkward silences of Godot, to the pointlessness of 'Endgame," to the brutal setting of Winnie buried to her neck in a mound of dirt in 'Happy Days," and so on. It gets worse. I wanted to convey a genuine sense of the Beckett world, but in a contemporary idiom—and all around me was terrorism. Not only locally in New York, of course, with the Twin Towers, but every day now, a present of terrorism—and its State corollary, torture. How to bring torture into my book, as a person who has never suffered it and could never deign to imagine it? I appropriated from the Guantanamo diaries of a Mauritanian held in Cuba with no charges for 15 years. The editor who edited the diaries, Larry Siems, understands my recontextualizing and is fine with it.”

Of course, Beckett himself was a witness to another terrorism, Nazism. He spent a lot of time in Nazi Germany in the late 1930s (he recorded in his diary, “All the lavatory men say Heil Hitler”). Was Beckett working for British intelligence? “During his time in the resistance,” says Coffey, “with the cell ‘SMH Gloria,’ he was working for British Special Operations. I don’t know of any evidence that he worked for the British before the war, on his trip to Berlin, for example, in 1936. But the SOE in London had a file on Beckett: ‘Well built, but stoops. Dark hair. Fresh complexion. Very silent. Paris agent.’ Beckett had an Irish passport, but he chose to stay in France after the war broke out.”

Beckett’s firsthand look at Nazism had a profound effect on him. “Beckett,” says Coffey, “was able to be coldly analytical about the horrors that were moving around him. He wanted to see art and people. He was appalled at the actions of the State and intrigued by the actions of artists. Art, I think forever remained in an endangered place, and he always defended it, his art of course, but that of many others.”

Coffey wonders what a 21st-century Beckett would be like. “What would Beckett be doing today?” asks Coffey. “Would he see possibilities for expression in the digital age? What would the expanses of the internet do to a Beckett performance space? He was attentive to all technologies and he would be to this one. He would probably dismantle it and we’d thank him.” Coffey pauses for a moment before puckishly saying, “Beckett with a Twitter account. Imagine.”

"Samuel Beckett Is Closed" by Michael Coffey. Foxrock/OR Books, $22, 208 pages

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising" and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," both now available in paperback, Kindle, and Audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his website and on Facebook.

* Originally published in May 2018. Updated in October 2025.

Comments