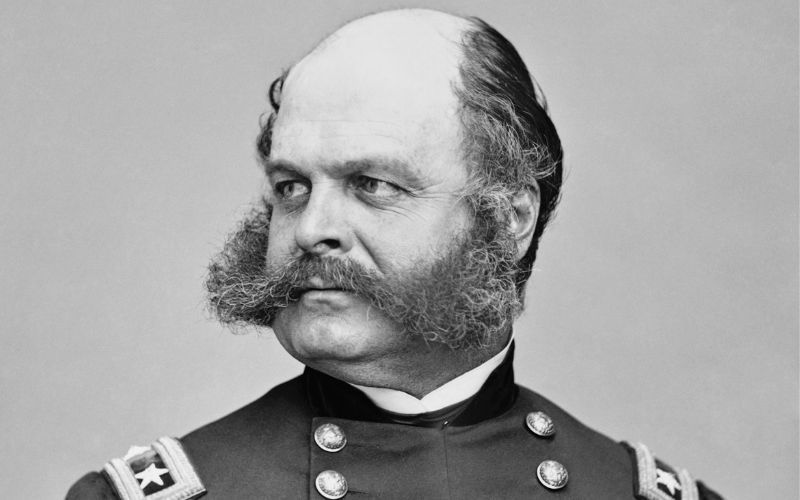

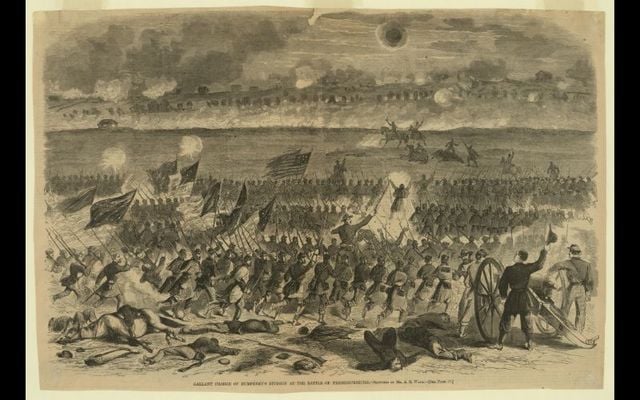

Four weeks after his Army of the Potomac absorbed a staggering 13,000 casualties at the Battle of Fredricksburg, General Ambrose Burnside surmised that more combat was the tonic that would improve the morale of his battered troops.

Burnside planned a surprise attack of the left flank of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

However, a four-day torrential downpour spoiled Burnside's plans. The roads became unpassable, trapping Union horses, wagons, cannons, and infantry in the Virginia mud.

What became known as Burnside’s “Mud March,” failed to raise troop morale.

Ambrose Burnside. (Public Domain)

Loathe to see his troops despondent, Burnside issued liquor to them on January 22. Another bad idea.

“Drunken troops began brawling, and entire regiments fought one another.”[2]

From the other side of the Rappahannock, Lee’s army laughed and hurled filthy insults at their hapless enemy.

After Burnside’s ill-advised “Mud March” and subsequent liquor bash, President Lincoln sacked him on January 25.

The next day, January 26, 1863, Private Patrick O’Hanlon had enough. The “Mud March” was his final straw. He filled his canteen, threw some food and ammo into his knapsack, and became one of more than 300,000 soldiers on both sides who deserted during the war. [3] He most likely took his pistol and musket and travelled back to New York, whether by foot, horse, or rail is unknown.

Patrick O’Hanlon was born June 23, 1841, in Lower Killeavy, County Armagh.

Armagh is an ancient place where prehistoric cairns and neolithic stone circles testify to the presence of people and pagan religions thousands of years before St. Patrick founded his first church there in 445 AD. Ruins of medieval churches, abbeys, and Norman towers still inhabit the landscape, constant reminders of time’s changing architecture and human fortunes. [4]

In 1850, at age nine, Patrick O’Hanlon emigrated to America, fleeing with millions of other Irish, the devastation of the Great Hunger.

Ireland's Great Hunger - Sketch of a Woman and Children represents Bridget O'Donnel. (Public Domain)

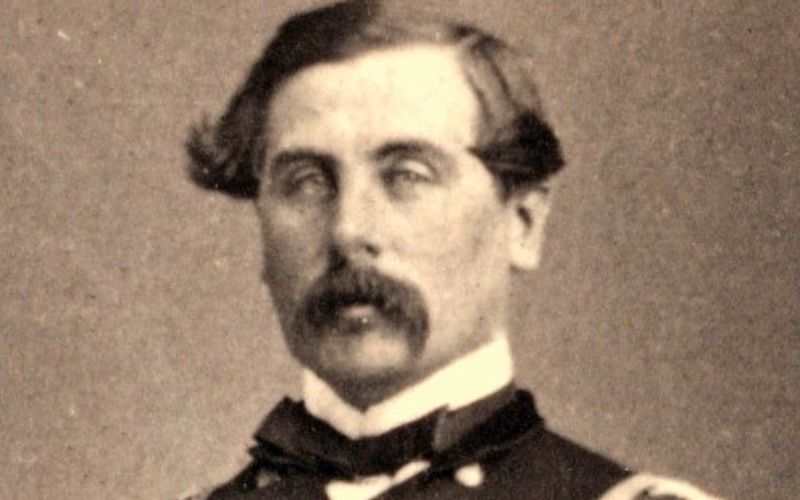

Eleven years later, in October 1861, 20-year-old Pvt. O’Hanlon became one of more than 150,000 Irish immigrants who joined the Union army. O’Hanlon himself was assigned to the newly constituted 63rd Infantry Regiment -- the Irish Brigade serving under former Irish revolutionary and legendary general, Thomas F. Meagher. [5]

Thomas Francis Meagher. (Public Domain)

Snapshot: O’Hanlon escaped the famine, which claimed the lives of millions of poor Irish, to live in abject poverty in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, and then volunteered to fight in America’s Civil War, a conflagration that claimed the lives of 650,000 to 750,000 men. [6

Until his desertion, O’Hanlon participated in all the Irish Brigade’s campaigns --Yorktown, Fair Oaks, Cold Harbor, Savage’s Station, Glendale, Malvern Hill, Frederick City, the bloodbath at Antietam, until finally, the insane assault on Fredricksburg. [7]

O’Hanlon’s name does not appear in any civil records until 1870. But he was most likely living in New York six months after his desertion, during the Draft Riots that took place in June of 1863.

Having experienced the brutality and the horror of combat and the disproportionate sacrifice of the Irish, O’Hanlon may have believed that the Irish were being used as cannon fodder to fight a “rich man’s war.” Most Irish, for example, could not afford the $300 to buy themselves out of the draft. [8]

No record survives revealing whether O’Hanlon, upon his return to New York, participated in the riots. Was he so exhausted from the bloodshed he had witnessed for two years that he avoided the riots? Or did he sympathize with the mob’s rage, a rage that allowed it to invade Black neighborhoods, loot stores, and murder between 120 and 300 Black men and women, hanging many from lampposts, and setting fire to a Colored Orphan Asylum that housed more than 200 children. [9]

The next record of Patrick O’Hanlon’s whereabouts is the 1870 federal census, seven years after the riots, where his name is listed as a resident of Wards Island — undoubtedly the sorriest piece of real estate in New York at the time. Wards Island, and its sister island, Randall’s Island, were aptly called “the islands of the undesirables.”

In the 1840s, more than 100,000 bodies were exhumed from “potter’s fields” in Madison Square Park and Bryant Park and re-buried in mass graves on Wards Island. A few years later, buildings were constructed on top of these graves. These buildings warehoused many of the tired, poor, huddled masses, as well as the wretched refuse of teeming shores and the homeless and tempest-tossed who had yearned to be free – warehoused safely out of sight of the general population.

The undesirables found “refuge” in places like The State Emigrant Refuge, the Dickensian-styled, ironically-named House of Refuge — a brutal housing complex for hundreds of criminals and street urchins, largely comprised of Irish teenage boys. Still other buildings included a rest home for Civil War veterans, an Inebriate Asylum, and the New York City Asylum for the Insane.” [11]

O’Hanlon most likely qualified for residence in the Civil War rest home unless his status as a deserter was an obstacle. Where else? Inebriate Asylum? Hospital for sick and destitute immigrants? Insane asylum?

How long he resided on Wards Island is unknown. O’Hanlon’s next known location is Jersey City where at age 36, he married Margaret Elliot on February 8, 1878. Maggie, as she was known, had emigrated from Tipperary in 1866 at the age of 13.

Patrick and Maggie resided on Grand Street in Jersey City, in the (now-posh) Paulus Hook neighborhood, for the duration of their marriage. He worked as a laborer, perhaps on the Jersey City docks near their apartment. Maggie was a homemaker and became a mother to their first son, Thomas, on October 15, 1879. Son William was born almost exactly four years later, on October 16, 1883.

On paper, the O’Hanlon family enjoyed four seemingly uneventful years.

But it was not to last.

On February 12, 1887, Patrick died of sepsis after having his leg amputated, whether from cancer, a work-related injury, or a festering old war wound. He was 46 years old.

Five months later, his four-year-old son, William, died of tonsillitis, leaving Maggie to care for young Thomas by herself.

One sad event piled upon another. Maggie herself died six months later at age 35 on February 12, 1888.

Thomas O’Hanlon, my maternal grandfather, was an orphan at age nine. My mother told me he may have been raised by an aunt, but no evidence of any sort is extant. His name next appears in civil documents when he married my grandmother, Mary Larity, in 1903. They raised ten children. [12]

This essay is dedicated to my wonderful granddaughter, Eileen Morrow, a student of the Civil War, and the great-great-great granddaughter of Patrick O’Hanlon.

[1] “January 20: This day in History –Mud March Begins,” History.Com. 13 November 2009.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Desertion was a difficult problem for both sides. “Official figures showed slightly over 103,000 Confederate soldiers and over 200,000 Union soldiers deserted” (Mark A. Weitz, “Desertion, Cowardice, and Punishment,” Essential Civil War Curriculum). The Confederate army numbered between 800,000 and 1,200,000 men. The Union army is estimated to have been slightly over 2,000,000 men. They deserted for a variety of reasons: unfamiliarity with the rigors and brutality of war, poor food, rampant disease, inadequate clothing and supplies, exposure to the elements, homesickness, concern for loved ones, battle fatigue.

[4] https:discovernorthernireland.

[5] Steve A. Hawkes, “63rd New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment: The Irish Brigade,” The Civil War in the East (2022).

[6] (“Who, What, Why: How many soldiers died in the US Civil War?” BBC News (4 April 2012).

[7] Kevin E. O’Brien, ed., My Life in the Irish Brigade: The Civil War Memoirs of Private William McCarter, 116th Pennsylvania Infantry. Savas Publishing Company, 1996.

[8] “The New York City Draft Riots of 1863,” https://history.com/topics/

[9] “The New York City Draft Riots of 1863,” https://history.com/topics/

[10] Bess Lovejoy. “Islands of the Undesirables: Randall’s Island and Wards Island,” Atlas Obscura, 2 June 2015.

[11] Ibid.

[12] All documents from family history are from searches in Ancestry,com.

* Originally published in Nov 2023, updated in May 2024.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments