The murder of an informer by a Donegal man, an American citizen, off the coast of South Africa on a steamship... "My name is Pat O'Donnell" is a local story recreated in an Irish folk ballad, with international dimensions.

It’s quite difficult for a young person nowadays to get any real sense of what life was like for people of their own age growing up in rural Ireland in the early 1960s and for many it would seem extraordinarily quaint. The Donegal Gaeltacht, the Irish-speaking region in the northwest of Ireland, in my formative years would now appear to have been a truly strange and weird world.

Electricity was a recent arrival and the modernization associated with it was a luxury to be respected, even prized. It would be some time yet before the wonders of television would penetrate into that closely knit community and, when it did arrive, it would be of a dull black and white variety depending on a patchy signal from a chimney top aerial.

But, curiously, a social media did exist there, albeit very different from the modern world of Facebook or Instagram. Ballads or folksongs were the medium that carried the people’s stories of both major and minor events - not just throughout the community but down through the generations as well.

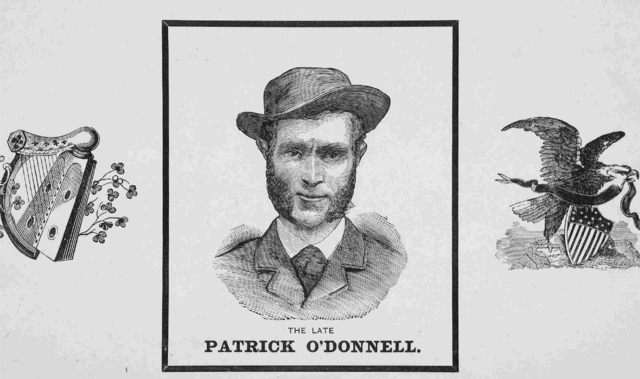

I recall as a child my late mother signing one such ballad, passed down over scores of years; ‘My name is Pat O’Donnell’. It told the intriguing story of a man from our neighboring parish, Gweedore, who became a national hero when he was hanged for murder in London in 1883. His heroism stemmed not from the act of killing itself but from the infamy of the Irishman he shot – an informer whose evidence saw five of his erstwhile colleagues hanged.

To add to the mystery, Patrick O’Donnell had spent much of his life in America and was a US citizen but the shooting happened in an exotic location, on a steamship on the high seas off the coast of South Africa – this really was a local story with international dimensions.

The lyrics of that ballad had remained locked away in my mind for much more than half a century when a television producer colleague was seeking a subject for a feature-length drama-documentary.

While ‘My name is Pat O’Donnell’ pointed me to a story of murder mystery, courtroom drama and political intrigue, I discovered very quickly, that not unlike modern social media, the folk ballads of yesteryear had their own substantial veneer of half-truths and hidden agendas.

Researching the life of Patrick O’Donnell brought me on a fascinating mystery tour of court transcripts, official records in archives in Ireland, Britain, South Africa and America, old newspapers of all kinds as well as many other sources to compile material, not just for a TV drama-documentary - "The Queen v Patrick O'Donnell" - but for a book of the same name.

And in the course of that research, in an archives file in London kept secret for over 100 years, I found what is generally termed a ‘smocking gun’ – shocking evidence that the Donegal man had been hanged as a result of the judge’s determination to find him guilty despite the jury’s belief that his crime was ‘without malice’.

Patrick O’Donnell (45), a laborer with no formal education, had been charged with the murder of James Carey, the leader of a violent Irish nationalist grouping called ‘The Invincibles’, who were responsible for the savage murder of two of the most senior political figures in Ireland; Thomas Burke and Lord Cavendish were viciously stabbed to death in May 1882 in what became known as the Phoenix Park murders. When arrested and in order to avoid conviction Carey turned informer and gave evidence that brought his former colleagues to the gallows. He was seen as one of the most reviled and despised figures in Ireland at the time and his evidence against colleagues was seen as treachery.

Patrick O’Donnell had spent much of his life in America. He left the US in 1883 with the hope of making his fortune in the diamond mines in South Africa. He unknowingly befriended Carey during the three-week sea voyage from London to Cape Town as the informer and his family attempted to flee into hiding under an assumed name.

When Carey’s was unwittingly unmasked and his true identity became known in Cape Town, Patrick O’Donnell was furious that had been misled by what he perceived as his ‘new best friend’. A skirmish between them escalated and O’Donnell shot and killed the informer on board a ship on the high seas. As the killing happened on a British-registered vessel in international waters, O’Donnell was subsequently extradited to London and charged in the Old Bailey, England’s most famous courtroom.

Patrick O’Donnell, had become accustomed to carrying a gun during his years in America, admitted to shooting Carey in front of witnesses but his stance was that the killing was in self-defense.

The presiding judge, Mr Justice Denman, told the court that the jury, as they concluded their deliberations having heard all the evidence during the two-day trial, had submitted a written question to him in which they had sought a definition of ‘malice aforethought'. His reply was widely reported by the media who attended the high-profile case.

However, the actual question posed by the jury which was not read to the court is included in a file on the O’Donnell case in the British National Archive which was ordered to be ‘Closed until 1985’. The handwritten note of the jury’s question in blue pencil was attached by Mr Justice Denman to 61 pages of meticulous notes made by him during the course of the two-day trial.

The question suggests that the jury had no problem in understanding the concept of ‘malice aforethought’ but rather sought to ascertain if they reached a verdict of ‘murder without malice aforethought’ would the judge accept that verdict.

The text of the question was: “If we find prisoner guilty of murder without malice aforethought can you take that verdict”.

Since a killing without malice equated to manslaughter it would attract a short prison sentence of a few years at that time. However, murder with malice aforethought carried a mandatory sentence of hanging. It was clearly a matter of life or death for Patrick O’Donnell that the judge misrepresented the jury’s question, withheld it in court and replaced it with an unasked question of his own. It was a critical deflection by him that left the defense team in the dark and paved the way to a guilty verdict.

O’Donnell was lauded as a hero for killing the informer whose death was celebrated throughout Ireland and in the Irish-American communities where he had spent half his life.

An ‘O’Donnell Defense Fund’ established in America accumulated $55,000 (c. €1.5 million now) to employ a high-powered legal team to defend him. Since O’Donnell had been granted American citizenship during his years there, the US President pleaded that the sentence of death be postponed pending efforts to mount an appeal. The iconic French writer Victor Hugo also took up his case and contacted Queen Victoria directly with an urgent request to spare the Donegal man’s life.

Such appeals were rejected and O’Donnell was hanged at Newgate Prison on 17th December 1883. His death secured his immediate status as a national hero at home and abroad and he was celebrated as an Irishman who had died for Ireland. Two large Celtic crosses were erected to commemorate him, one in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, the second in his native Gweedore, where a public event in his honor is still celebrated annually.

And the social media ballad of my youth is still recalled by my generation. The interest it sparked in me as a boy was the seed from which grew both the film and book entitled ‘The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell’.

This article was originally published in the September / October 2021 issue of Ireland of the Welcomes. Subscribe here.

Comments