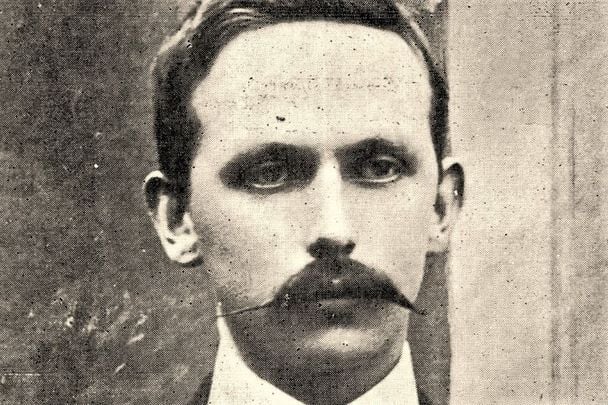

Born in Glenamaddy, County Galway in 1881, Éamonn Ceannt would grow up to be a pivotal figure in Ireland’s fight for independence. Raised in Dublin and steeped in republican ideals, he became one of the seven signatories of the 1916 Proclamation and a leader in the Easter Rising. Writer and historian Dermot McEvoy profiles the rebel leader, telling his individual story.

Éamonn Ceannt was born Edward Thomas Kent (not to be confused with Thomas Kent, another rebel who was shot in Cork) in County Galway in 1881, but was raised in Dublin. He is probably the least well-known of the seven signatories of the Proclamation.

He was educated at the Christian Brothers’ School in North Richmond Street which must have been a hotbed of Fenianism because both Seán Heuston and Con Colbert also went there.

He has been described as hard to get along with, but admitted his “cold exterior was but a mask.” His letters to his wife show a different, gentler, side of Ceannt. When he was romancing his wife, Áine, he wrote: “No news to tell at all little girl but to remind you that in a few months’ time, with the help of God, you will have become my prisoner forevermore . . . a new little wife you’ll be that first day, owned by a man, bossed by a man, loved by a man.”

Ceannt immersed himself in Irish culture joining the Gaelic League and had a special love of music, mastering the Irish uilleann pipes, which he played for Pope Saint Pius X at the Vatican in 1911. He was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood by Seán MacDiarmada that same year and was a member of the Irish Volunteers from its inception. Soon he was the Commandant of A Company, Fourth Battalion.

On the way out on Easter Monday, Áine recalled the final conversation between father and son: “Turning to Ronan, who was watching us, he kissed him and said to him in Irish: ‘Goodbye Ronan.’ ‘Goodbye Dad.’ ‘And won’t you take care of your mother?’ ‘I will, Daddy.’ ”

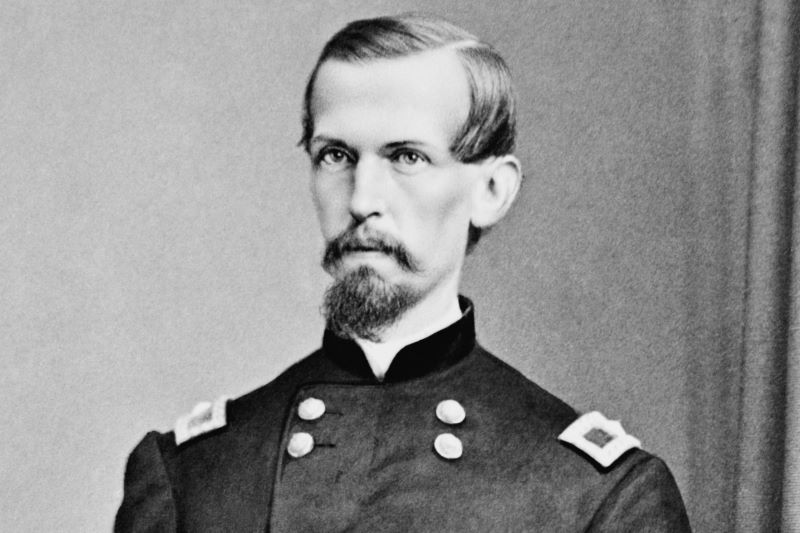

Éamonn Ceannt was stationed at the South Dublin Union when the Easter Rising began

His objective on Easter Monday was the South Dublin Union. Perhaps the best description of this sprawling complex is by Mick O’Farrell in his terrific book, 'A Walk through Rebel Dublin 1916': “…[T]he South Dublin Union [was] strategically important because of its position near not only the Royal Hospital, but also two barracks, and the main Dublin railway station. The Union, now the site of St. James’s Hospital, was a huge area of buildings and open fields. With halls, wards, sheds, dormitories, streets, courtyards, and two churches, it was a complex bigger than a lot of Irish towns at the time. Its walls also enclosed about 52 acres of fields and lawns. And housed within the sprawl were 3,282 inmates.”

Ceannt’s second-in-command was the fearless Cathal Brugha, who ended up being badly wounded but who would survive to become a member of the First Dáil and the nation’s first Minister of Defence. From the outset there were problems.

Rebel leader Éamonn Ceannt had problems from the outset

First, Ceannt didn’t have enough men and those men were being consistently harassed by snipers. The battle for the South Dublin Union was one of the bloodiest battle scenes of Easter Week.

After his surrender, Ceannt told a British officer, “It would surprise him to see the small number who held the place.” And he later wrote proudly of the “magnificent gallantry and fearless, calm determination of the men.”

Ceannt marched his men to St. Patrick’s Garden and surrendered. At Richmond Barracks he was quickly picked out by detectives of the G-Division of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (who would soon be terrorized by Michael Collins’ famous Squad).

Éamonn Ceannt's trial post-surrender was full of inaccuracies

His trial was a travesty with witnesses saying Ceannt was over at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory. He called John MacBride in his defense and wanted to call Thomas MacDonagh, Jacob’s commandant, but was told MacDonagh was “not available” – he had been executed that morning.

He wrote down advice for future battles: “I leave for the guidance of other Irish Revolutionaries who may tread the path which I have trod this advice: Never to treat with the enemy, never to surrender at his mercy, but to fight to a finish. I see nothing gained but grave disaster caused by the surrender, which has marked the end of the Irish insurrection of 1916…the enemy has not cherished one generous thought for those who withstood his forces for one glorious week.”

“My dearest wife Áine,” he began his last letter, “not wife but widow before these lines reach you. I am here without hope of this world, without fear, calmly awaiting the end . . . What can I say? I die a noble death for Ireland’s freedom. Men and women will vie with one another to shake your dear hand. Be proud of me as I am and ever was of you.”

Just before he was marched out to the Breaker’s Yard Father Augustine said to him: “When you fall, I will run out and anoint you”

“Oh,” replied Ceannt, “that will be a grand consolation, Father.”

Éamonn Ceannt was shot between 3:45 and 4:05 a.m.

The British did not have the courtesy to tell Ceannt’s wife that he had been executed. She traveled to the Church Street Priory to find out what had happened to her husband. “He is gone to heaven,” she was told.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his Facebook page.

*Originally published in 2016. Last updated in 2025.

Comments