By the end of World War One in 1918, 200,000 Irishmen were involved in the conflict, proportionately the greatest deployment of armed manpower in the history of Irish militarism.

Irishmen had been awarded the Victoria Cross, awarded for valor in the presence of the enemy, since its creation in January 1856 by Queen Victoria.

30 Irish VCs were awarded in the Crimean War, 59 Irish VCs in the Indian Mutiny, 46 Irish VCs in numerous other British Empire campaigns between 1857 and 1914, 37 Irish VCs in World War I, and eight Irish VCs in World War II.

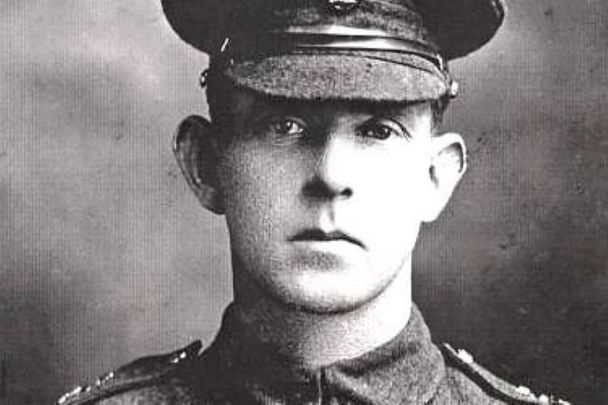

James Duffy, a native of Gweedore in Donegal, became one of the Irish recipients of the VC, the highest level of gallantry available to a soldier serving in the British Army. This is his story.

Duffy was born on the 17th of November 1889 in the parish of Gaoth Dobhair in Donegal to his mother Catherine Doogan and father Peter Duffy.

Peter was working in Bonagee, Letterkenny, and the family joined him when James was just a few months old. James attended a local primary school in Drumlodge, near Letterkenny.

His father was employed on a seasonal basis in the agricultural and fishing industries, picking up work wherever and whenever he could. James would go on to try his hand at fishing but like so many of the young men in Ireland at that time it was not long before he crossed the water to Scotland to Glasgow. He quickly found work in the massive shipyards that lined the River Clyde working in the famous John Brown Shipyard in Clydebank.

When war broke out, James was still working in the shipyards, but along with thousands of other young men swept up in the jingoistic fever of the time, he quickly enlisted. He did so on the 1st of December 1914, joining the 6th (Service) Battalion, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, which had been raised in Omagh, Co. Tyrone, in August.

The battalion was part of the 31st Brigade, 10th (Irish) Division, the first complete Irish division to serve with the Army. The constituent member regiments were drawn from Ireland’s four provinces and its early training took place in the Dublin area.

The Division moved to Basingstoke, Hampshire in May 1915 and was earmarked to participate in the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign which had stalled and descended into the static trench warfare that had blighted the western front.

In July, Duffy and his regiment embarked for the Gallipoli Peninsula, arriving on Mudros on the 7th of August. The 10th (Irish) Division later landed on “C” Beach, south of Suvla Bay, and Duffy was soon busy as the battalion went into action.

While the landing was successful, heavy fighting continued throughout August as the Allies attempted to expand the beachhead they had created and move inland.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

However, the offensive failed. During the summer months the hot conditions, and a constant struggle by the allies to supply enough fresh drinking water to its troops, meant that conditions at Gallipoli were awful. Large numbers of troops, on both sides, succumbed to a dysentery epidemic that spread across the peninsula in the late summer.

The cost of Gallipoli was enormous in terms of human life, with an estimated 130,000 men losing their life in action or from diseases contracted while on the peninsula. In that total are approximately 4,000 Irish men who never returned home.

The 6th Royal Inniskilling’s were later transferred to the Salonika front on the 24th of October and were involved in the fighting of the 7th and 8th December, at Kosturino and then Karajakois, and remained in the theatre of operations until September 1917, when they were posted to Alexandria, to prepare for the forthcoming invasion of Palestine.

On the 1st of November, the battalion captured Abu Irgeig and took part in the successful operations in the Third Battle of Gaza when the British forces under the command of General Edmund Allenby successfully broke the Turkish defensive Gaza-Beersheba line. The critical moment of the battle was the capture of the town of Beersheba on the first day by Australian light horsemen.

Throughout his time in Palestine, Duffy was kept busy in his role as stretcher-bearer, and on the 27th of December, he performed the following act which was to lead to the award of the VC:

"While his company was holding an exposed position, Private Duffy (a stretcher-bearer) and another stretcher-bearer went out to bring in a seriously wounded comrade; when the other stretcher-bearer was wounded, he returned to get another man, when again going forward the relief stretcher-bearer was killed.

"Private Duffy then went forward alone, and under heavy fire succeeded in getting both wounded men undercover and attended to their injuries. His gallantry undoubtedly saved both men's lives, and he showed throughout an utter disregard of danger under very heavy fire”.

Six months after the fighting in which Duffy performed his heroic deeds, the battalion was sent to France and landed at Marseilles on the 1st of June 1918.

James Duffy was presented with his Victoria Cross by King George IV in the quadrangle of Buckingham Palace on the 25th of July 1918, and later returned home to Bonagee, Donegal where he was given a rousing reception.

Later that year, James married Maggie Hegarty, and the couple went on to have seven children and twenty-four grandchildren. Duffy was demobilized in 1919, little knowing that he was never to enjoy the luxury of regular employment again.

If he did find work, it was usually as a casual laborer on the roads or on farms when the harvest was due in, but ill health and the situation in Ireland during the 1920s conspired against him, which included being kidnapped by the IRA in 1921, because he had served in the British Army and was of a higher profile than many others because of the VC.

It appears that Duffy missed out on several VC events, including the VC Garden Party of 1920 and the service for the Unknown Warrior, due to the non-arrival of the invitations which were incorrectly addressed. The matter was resolved in time for the 1929 House of Lords VC Dinner and Duffy attended the event.

In 1934, he took part in the Armistice Parade in Derry, but his ill health continued to cause problems for him, and he was living off a disability pension for malaria and rheumatism of 13 shillings and 6 pence a week, out of which he had to pay 2 shillings and 6 pence for the rent of his cottage in Bonagee.

When he was ill, Duffy was sent to Leopardstown Hospital, Dublin, where he received a much-needed boost to his income with a weekly grant of 25 shillings from a fund set up by a wealthy American businessman for distressed VC recipients and the Royal British Legion assisted when they could.

Duffy’s misery continued when his wife passed away in 1944, and it is reported that pressure from within the family to sell the VC to the highest bidder may have caused some friction, but Duffy bequeathed his medals, in the event of his death, to his former regiment in 1949.

In 1956, he attended the Dublin Festival of Remembrance, where he joined three other VC recipients, Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart VC, KBE, CB, CMG, DSO (1916), Joseph Woodhall VC (1918), and John Moyney VC (1917), and later the VC Centenary celebrations in London. Two years later, he was invited to a dinner held in Dublin to commemorate the six Irish regiments that were disbanded in 1922.

Duffy was, like many other VC recipients, reluctant to speak of his actions that led to the VC and would often play down the award, but the medal attracted attention and on at least one occasion Duffy was visited by Earl Mountbatten during one of his regular summer holidays to Ireland.

In 1966, Duffy met the Queen when she attended the 50th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme at the Balmoral Showgrounds, Belfast.

On the 7th of April 1969, following a long illness, Duffy passed away at Drumany, Co. Donegal, and was buried in Conwal Cemetery, Letterkenny, Co. Donegal.

He was afforded a full military funeral which was arranged by Major George Shields, Chairman of the Belfast branch of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers Regimental Association, and who had served with Duffy in 1917, and by Archdeacon Louis Crooks, who had become a good friend of Duffy’s.

The funeral began at Duffy’s cottage and his coffin had to be passed through the sitting room window and was carried by eight members of the Royal Irish Rangers, led by CSM William O’Neill and the cortege was led by Piper Major James Creggan who played the lament “Flowers of the Forest”.

A Requiem Mass was held at St. Eunan’s Cathedral in Letterkenny and then moved onto the cemetery passing through the town.

The shops and offices closed, lorries, cars, and buses were parked up on the side of the road and their drivers stood along with the majority of the population in silence as the cortege passed, and it was reported that the only sound to be heard was the clink of the medals of the old soldiers.

Duffy was laid to rest beside his wife and several wreaths were laid before Lance-Corporal J. Maxwell, played The Last Post and then Reveille at the graveside.

Duffy left five sons and one daughter and in 1997, one of the sons, Hugh, was buried with his parents. Ten years later, a stone bench was unveiled in Letterkenny Town Park on the 10th of July 2007 to honor Duffy. His daughter Nellie was present when former Letterkenny Mayor Ciaran Brogan unveiled the bench in one of his final duties in the office.

Private Duffy was again honored when Chaplain to the Irish army's Finner Camp, Bundoran, Fr Alan Ward celebrated a Mass in his memory at Donegal County Museum. Private Duffy's Victoria Cross was brought from the Inniskilling Museum for the service.

In November 2017, the Ulster History Circle unveiled a blue plaque at Castle Street, Letterkenny in his honor.

* Originally published in 2021, updated in Aug 2024.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments