“To come out of this crisis better,” wrote Pope Francis mid pandemic last November, “we have to recover the knowledge that as a people we have a shared destination. "The pandemic has reminded us that no one is saved alone.”

No one is saved alone. No one ever makes it on their own. Because the smallest indivisible number is two, not one, despite what they teach you in school.

Last year the pandemic stopped us in our tracks, just like the experience of a sudden unexpected illness had once stopped Pope Francis when he was 21, almost killing him. He survived, he writes because two experienced nurses had the sense to double the doses of penicillin and streptomycin his doctor had prescribed.

“What ties us to one another is what we commonly call solidarity,” Francis wrote in his remarkable article published in The New York Times. “Solidarity is more than acts of generosity, important as they are; it is the call to embrace the reality that we are bound by bonds of reciprocity. On this solid foundation, we can build a better, different, human future.”

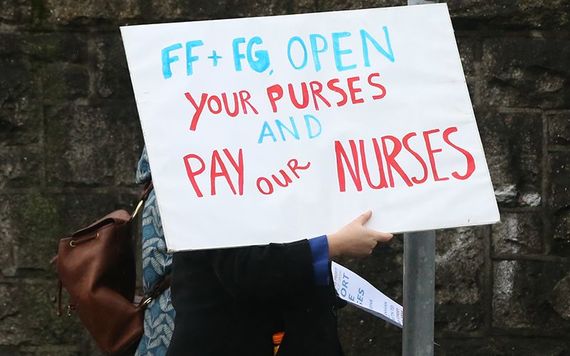

Well, we saw it over and over. Solidarity and reciprocity blossoming internationally. Health care workers, nurses, and doctors, risking their own lives in service to the greater good. It was the most perfect illustration of global solidarity and reciprocity that I have ever seen.

Right now the whole rented world, or at least the vaccinated western half, is trying to start up the old grinder of casual, short-term exploitation as though the pandemic were a blip instead of a rubicon. Old reflexes are anxious to reestablish the world just as it was as if that were still a thing that could happen now that we have seen just how precarious and transient the whole business of living actually is.

Politicians and pundits are already thronging to gaslight us into believing that what we lived through was a modulation rather than a metamorphosis. Get back in your box, put your head down, move along, there was nothing to see here, they insist.

In America, we now have one party under President Biden that wants to enact a program of ambitious and in some cases unprecedented national reforms. The other party, still under the spell of their exiled Florida-based leader, is increasingly the party of angry internet trolls, a sort of animate Yahoo comments section whose main goal now, it seems, is to inspire and drink liberal tears, to exult over the fellow American citizens they hate, because it can feel like a sort of victory.

So the stakes have never been starker or higher for the nation, in other words, and it is not at all clear to me which of our angels will prevail. Will we embrace the easy politics of hostility and division, or will our experience finally teach us the hard wisdom of E Pluribus Unum (out of the many, one)?

Is our destination shared now? Was it before the pandemic? Do we have an opportunity to change our course now? Do we have the courage to do it? Are we all in this together? Shouldn't we be?

And some of us, like Pope Francis, are a little further ahead on the profound implications of this realization. His own proximity to death once taught him that the business of living is so much more urgent than he had ever imagined – and that it was everywhere and always shared. It will be interesting to see how this nation grapples with what it has just learned from the same lesson.

Comments