It's fascinating how long it can take people to recognize and make modest reparations for a wrong performed either by themselves or their ancestors.

Take the descendants of 19th-century British aristocrat Sir Charles Trevelyan. In Ireland, his reputation has long preceded him as the subject of "The Fields Of Athenry," the famous ballad about a destitute Irish man who's prosecuted for stealing “Trevelyan's corn,” a reference to the abundant foodstuff exported from Ireland whilst millions were starving to death there in the Great Hunger.

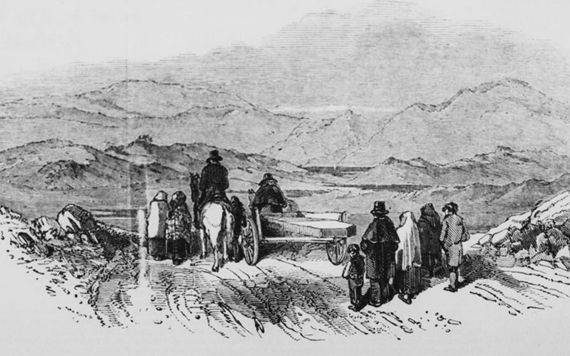

A funeral cortege at Shepperton Lakes, West Cork, Ireland during the Great Famine (aka the Irish potato Famine), 1847. Sketch by James Mahony. Original publication - Illustrated London News pub 13th February 1847. (Getty Images)

Trevelyan's well-to-do descendants made the news recently when they were “shocked” to learn of their ancestors' prominent role in the slave trade of captured Africans in the Caribbean.

It seems incredible to me that one can amass both fabulous wealth and aristocratic titles without wondering about the rough work that preceded them, but I may not be the most sympathetic observer. Often, prominent people tell themselves it was due to their merit, or to being favored by God, or both, I suppose.

But there was less thought of personal merit and more thought of personal gain during the Trevelyan family's deep involvement in slavery in the 18 and 19th centuries, an involvement that “amounts to crimes against humanity” according to John Dower, a current family member.

The Guardian reported that Dower was working on the family history alongside his relative Humphry Trevelyan when they found the Trevelyan name repeatedly appearing in the University College London slavery database.

“What I read shocked me as it listed the ownership of 1,004 slaves over six estates shared by six of my ancestors,” Dower told the press.

“I had no idea,” he continued. “It became apparent that no one living in the family knew about it. It had been expunged from the family history. I was more than shocked, I was badly shaken,” he added. “I was under the impression that I came from a benevolent, public service-facing family.”

The benevolent, public service-facing Trevelyans? Try not to laugh. That last sentence tells us just how little our Irish history or indeed our current affairs, actually matter to the British.

Normally we are beneath their notice until a sitting US President like Joe Biden makes us ground zero of his re-election campaign as well as a deeply personal family pilgrimage site. Then suddenly we are depicted as drunken leprechauns in the British press, dehumanizing reminders of just how low we still rank in their chauvinistic Who's Who.

It takes a special kind of pathology, I have written, to export food from a starving people as they literally drop from hunger in the streets, but 19th-century colonial administrator and civil servant Charles Trevelyan possessed it.

“The real evil with which we have to contend,” Trevelyan famously wrote, “is not the physical evil of the Famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people.”

It wasn't enough that the English had stolen our land, our liberty, and livelihoods, Trevelyan then blamed us for the theft.

This week, it seems his fabulously wealthy descendants, who have donated an underwhelming £100,000 to the Caribbean island of Grenada to compensate for their ancestors' historic role in the slave trade, may finally have Ireland in their sights.

“If the Irish government said the Trevelyan family are liable for what Sir Charles Edward did, then of course that would have to be considered,” Laura Trevelyan, who is now a slavery reparations campaigner, having worked for the BBC as a correspondent in the United States, told the press.

Working for the BBC brought the “unsuspecting” Trevelyan into contact with outraged republicans, who could not believe her lack of awareness of her own history was genuine.

“And I remember so clearly being in Crossmaglen in south Armagh and speaking to a member of Republican Sinn Féin who looked at me in horror and said, 'How can you be driving around south Armagh with the blood of the Irish on your hands?'

"And to my embarrassment, I didn't even really understand what either of them were talking about. When I got back to Britain, I began to read up on Sir Charles.”

People who profit from others' misfortune rarely ask themselves where that fortune came from or if it was deserved, so this is a commendable decision on her part.

But like a lot of British aristocrats, she has other murky storylines to consider. One of her ancestors invented the Winchester repeating rifle, which was used to annihilate the Great Plains buffalo and slaughter tens of thousands of Native Americans in the brutal expansion of the American frontier. That's a lot of killing to come to terms with. She has her work cut out.

Comments