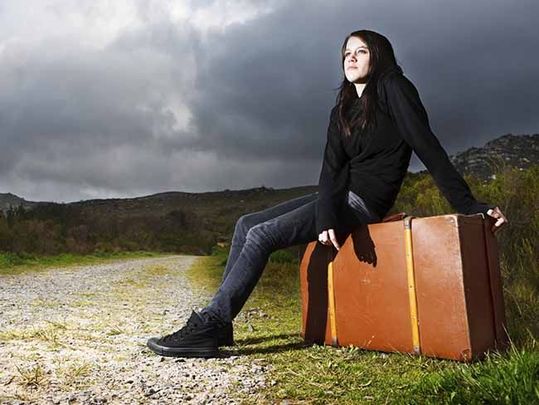

In Ireland, it has so become the norm, over the centuries and decades, for young Irish people to leave that making Ireland your home is almost an act of rebellion.

The summer I finished my Leaving Cert in the late 1980s, everyone, my age vanished, literally overnight, as though an A-bomb had dropped that only vaporized 18-year-olds.

They disappeared to college or training schools or abroad as new emigrants to England, America or Australia. After seeing them almost every day for most of my life I never saw many of them again, even for the week of Christmas. It was as though they had vanished into the air.

You can't really grow up if your story is uprooted. You can't develop a dispassionate response to your home place if the manner of your leaving still feels raw and unresolved.

Think of it, how many times have you sat at a barstool or in a kitchen somewhere listening to another young Irish person unburden themselves about the pain of that final severance?

Only later on did it occur to me that part of the reason why our young, our most unruly citizens, are dispassionately stamped for export year after year goes far beyond mere questions of economics, it's a political policy too. It's a terrifically handy way of consciously and subconsciously neutralizing their challenge to the status quo.

When you leave your home nation at 18 or just after college at 21 or 22 you still haven't had time to fully grasp the nature and character of the place that you grew up in. You're still too young for that.

Instead, you can carry an image of Eden superimposed over an image of austerity or economic collapse. That's a hard image to reconcile, and most people don't. Usually, they just airbrush the image until it becomes one or the other. Paradise lost or an escape from limbo. It rarely occurs that neither image is true.

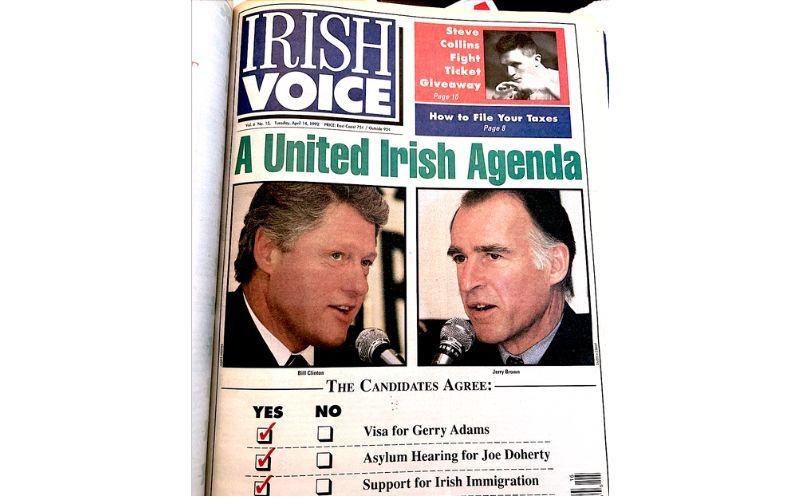

But it occurred to me before I even stepped on board Aer Lingus 105 to New York in 1996 that I have always been an immigrant, even at home. Let me explain what I mean.

Growing up discreetly closeted in Donegal in the 1980s I used to watch my friends heading out to discos or GAA matches or parish hall dances or fleadh ceoil's or summer festivals in search of a bit of craic, which they invariably found. They looked like they were having the time of their lives to me. Donegal, I used to think, looks like a wonderful place. I wonder if I'll ever be allowed to live in it?

I'm not joking about that. I grew up in a time when to be gay was a crime. You could be arrested for it. So I often felt like I was living under an occupation, on both sides of the border, because like every other gay person I knew at the time I was always waiting for a knock at the door, which would mean some form of public exposure, which would, in turn, mean social rejection and ruination, which turned out to be fatal for some.

Don't get me wrong, I wasn't hiding in my attic like Anne Frank. I wasn't threatened with transportation to Bergen-Belsen. Instead I, like every other unwelcome blow in, was simply marked for purdah, that particularly silent place at the edge of every Irish town or village where we banish the misfits, the socially threatening, the men and women who at face value don't seem to have an immediately reassuring role in the life of the place.

The message was always the same: you're here on sufferance, you don't really belong here, we can revoke your passport and your freedom anytime we like.

We are very good at making our problems vanish in Ireland. What were Magdalene Laundries and Industrial Schools and Mother and Baby Homes and all those other hells on earth but a way to legislate unwelcome people out of existence, after all?

We all walked quickly past those gloomy old holes for a century and a half, sometimes shivering with dread, but relieved it was happening to someone else and not us. Every Irish person understands that ruthless social contract, we knew in our bones what happened to the people in those places.

We are also ruthless about who gets a speaking part and who doesn't in Irish society. We can police each other with the kind of attentiveness that actually does suggest military guards. We do this to prevent politically and socially threatening conversations from happening. Because those conversations threaten the status quo. So we escort them off the premises and even off our shores.

That's why when I am asked to describe myself now the first word that comes to mind is immigrant. I once was an immigrant in my own country (people from Donegal were considered neither here nor there, gay people were even worse) and now I'm an immigrant here in America.

Making yourself at home is the most radical act you ever can perform as an Irish person. It's a radical act because we have not always been assured of a welcome, even in our own nation.

It's literally a mini-rebellion. And in Ireland itself now, where property and rent prices are through the roof and hardworking young people increasingly have no chance of securing a mortgage or making a home purchase, it looks like it's only getting started.

Comments