To "disrupt the morale of the English Secret Service, to a point at which its efficiency ceased to be the proud thing that it always had been.”

In 1935, only 14 years after the Irish War of Independence had ended, Hollywood turned Liam O’Flaherty’s novel, “The Informer,” into a motion picture. John Ford directed Victor McLaglen, who played a British tout named Gypo Nolan, who betrays Irish Republican Army gunman, Frankie McPhillip.

The film was a tremendous success winning four Oscars: Ford as Best Director; McLaglen as Best Actor; Best Screenplay for Dudley Nichols; and Best Musical Score.

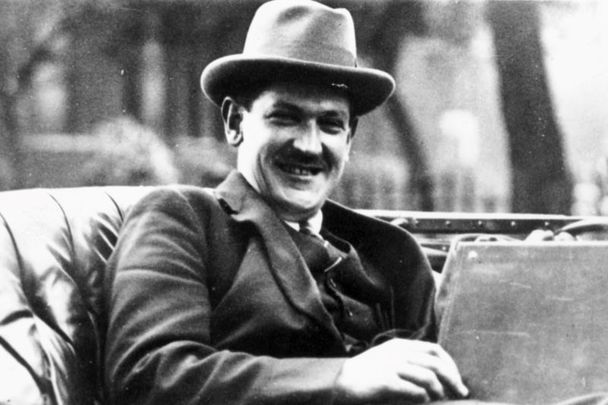

One of the worst things one Irishman can accuse another Irishman of is being an “informer.” It is a term that has become rancid after nearly 800 years of British occupation on the Irish island. One man who felt the same way was Michael Collins, Director of Intelligence (DOI) of the IRA.

Michael Collins targets informers

Collins is known for a lot of things—breaking de Valera out of Lincoln Gaol in England, as Minister for Finance floating the National Loan that helped the infant Irish nation survive financially, being head of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and being a Commandant-General of the IRA. It was a pretty full portfolio.

But according to Collins himself, the two things that bedeviled him the most as DOI was his twofold mission of besting the British Secret Service and their long-line of touts and spies, most of whom were ordinary Irishmen willing to sell their country out for British silver.

We know this because of “Michael Collins Own Story” by Hayden Talbot. This book was supposed to be Collins’ autobiography, but he died before it was finished. In it, he tells Talbot about his plans for Ireland and, of course, his most complicated job, the elimination of the British Secret Service—the eyes and ears of the British in Ireland—, particularly in Dublin.

In 1919 Collins set up a two-headed operation to handle the British Secret Service. First, he opened an intelligence office at #3 Crow Street, just off Dame Street, and just two blocks from Dublin Castle itself. He put Liam Tobin in charge of this office as Deputy DOI.

Michael Collins in uniform.

His second move was to establish an Active Service Unit (ASU) to handle touts, spies and British Secret Service. They were known as the Squad and more colorfully as Collins’ “Twelve Apostles.” Once a spy, a tout, or a member of the Dublin Castle intelligence “G”-Division had been identified the Squad would warn them. If they didn’t heed the warning they would be roughed up. If they still persisted, they would be eliminated.

Read more

Michael Collins besting the best secret service in the world

In Talbot’s book, Collins lays out his plans for both local informers and the British Secret Service. He is quick to note the damage the Secret Service did to Ireland over the centuries.

“The English Secret Service in Ireland,” Collins said, “with its unlimited supplies of money, had been unquestionably able to reach men of influence and position within our organization. Most of these traitors met their just desserts down through all the years.”

“Thus,” he continued, “every Irish youth for many generations had known in a general way of the English spy system, and how it had been always tremendously strengthened by the help of renegade Irishmen. But up to the end of 1918, we had done little to combat it.”

The size of the impending job did not frighten Collins.

“The English Secret Service in Ireland for centuries had broken every movement ever attempted by Irishmen to make Ireland an independent nation. The espionage staff of the British forces of control in Ireland, operating from their headquarters in Dublin Castle, was a body to which England had every right to point with pride. It was a costly organization to maintain, but it was maintained regardless of cost—the annual total in pre-war times having been approximately £250,000. This was the expenditure when there was little or no talk of an Irish revolutionary movement. Following the outbreak of the world war, even before the Easter Week rising, the cost of administrating the spy system has been reckoned to have totaled a million pounds a year.

“Now the time had come to turn our attention to the most important part of our job—the smashing of the English Secret Service. My final goal was not to be reached merely by beating it out of existence—I wanted to replace it with a better, and an Irish Secret Service. The way to do this was obvious, and it fell naturally into two main parts—making it unhealthy for Irishmen to betray their fellows, and making it deadly for Englishmen to exploit them.”

Then Collins said something amazing: “It took several months to accomplish the first job—actually the most important part—and hardly more than a month to disrupt the morale of the English Secret Service, to a point at which its efficiency ceased to be the proud thing that it always had been.”

In other words, handling the local informers had been a tougher job than disrupting the British Secret Service.

Spies beware!

Collins wrote about his “two most urgent problems”:

Number one “beating the English Secret Service until it was powerless.”

Number two“cleaning our own house until the last traitor Irishman had been identified and fittingly dealt with”

You would expect Collins to be focused on the British, but his focus was just as heavy on domestic informers, the local Gypo Nolans.

“It was a job of Herculean proportions,” Collins said, “and until and unless it was done thoroughly, freedom could never come to Ireland.

“Before we could turn our attention to the Black and Tans,” Collins continued, “we had to create our own organization and first use it to clean English spies out of the Irish Republican Army. This alone was no easy task, but before it was finished there were left within the Irish Republican Army only men who were whole-heartedly prepared to give their lives for Ireland.”

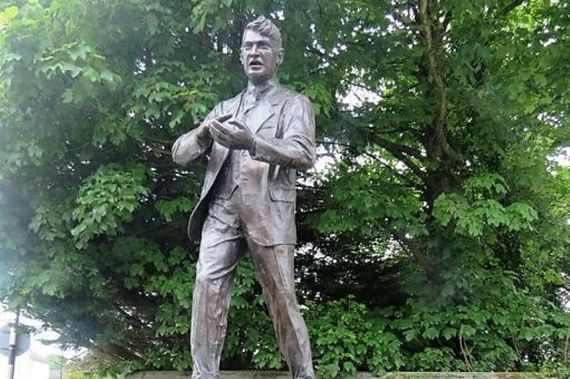

A statue of Michael Collins. (Ireland's Content Pool)

Many men in positions of power in the Republican movement thought Collins insane.

“Within the inner circle of the Irish Republican Army,” said Collins, “there was no unanimity of opinion that the new policy was wise—men like [Cathal] Brugha and [Austin] Stack, who cherished the delusion that we could by the use of force alone drive the English army out of Ireland, having no faith in Irishmen’s ability to outwit English brains. Perhaps, because I, more than anyone else, disputed this admission of inferiority, it was upon my shoulders that the heavy task of solving this twofold problem was laid.”

Bloody Sunday

With the banishment of the domestic spies and touts, Collins went for the big prize—the British Secret Service. On the morning of November 21, 1920, at exactly 9 a.m. Collins’ Squad, supplemented by members of the Dublin Brigade including future Taoiseach Seán Lemass, struck. The end result was the assassination of 14 British spies brought into Dublin from all over the Empire for the sole purpose of getting Michael Collins.

In essence, the war was over. Collins knew it and so did British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. It would take eight long months for the British to find a way to extradite themselves from their Irish quagmire. The truce of July 1921 would end the carnage and bloodshed and on December 6, 1921, Collins signed the Treaty that created the Irish Free State which would by 1949 morph into the Republic of Ireland.

After 700 years of British occupation, Collins had basically in little more than three years, between 1919 and 1921, brought freedom to most of Ireland. It took a draconian policy of terror on the part of Collins, but it, in the end, succeeded by eliminating spies, both domestic and foreign, from the streets of Dublin.

*Originally published in 2019, updated in August 2020.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising," and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," both now available in paperback, Kindle and audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He can be reached via email at [email protected] and on his website and Facebook page.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments