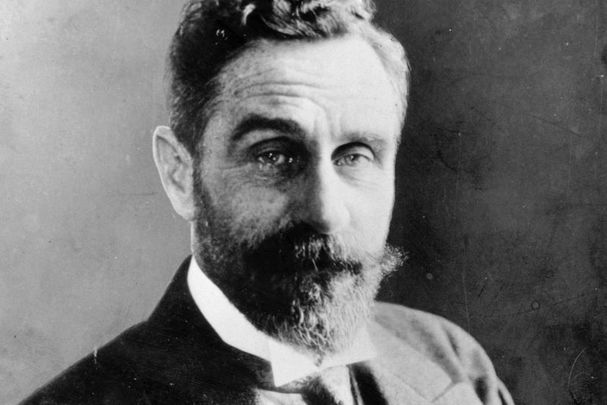

Sir Roger Casement had received a knighthood just five years before he was executed in Britain for his role in the 1916 Easter Rising on August 3, 1916.

Roger Casement was born into a Protestant family in Sandycove, Co Dublin, on September 1, 1864. Educated in Ballymena, Co Antrim, he left school at 16 and went to work for a shipping firm in Liverpool.

In 1884, Casement went to Africa to work for the African International Association, where he learned firsthand what European colonization was perpetuating on the inhabitants of the Dark Continent. He eventually went to work for the British Colonial Service before transferring to the British Foreign Office in 1901.

While in the consular service, he witnessed many atrocities connected with the rubber trade in the Congo Free State, a colony under the control of King Leopold II of Belgium. In 1904, he was commissioned to write a report on these human rights violations, including slave labor and mutilations of the limbs of some of the natives. The Congo Report caused a sensation and brought Casement into the public spotlight.

Casement’s next posting was to South America in 1906. There, he came upon even worse brutality against the natives in the Peru rubber trade, where such things as death sentences by starvation were carried out. For his findings on the two continents, he was awarded a knighthood in 1911.

His experiences soured him on imperialism and colonialism. The exploitation he found in Africa and South America, he believed, was not unlike what the British were propagating in Ireland. He decided it was time to burrow his way into the revitalized Irish national movement.

He began to contribute anonymously to "The Irish Review" edited by Joseph Mary Plunkett, and they became friends. Casement was thought of highly by the Plunkett family: “Casement was a fine, sincere and very intelligent man, remarkably kind and charitable,” Geraldine Plunkett Dillon wrote in her autobiography "All in the Blood."

“Casement called himself ‘the leprechaun of Irish politics,’….My father [Count Plunkett] and Joe admired him very much and we always heard him spoken of with respect and liking.”

Unfortunately, these salubrious feelings were not shared by most of the Fenian leadership, especially Thomas Clarke, the old Fenian jailbird who was putting the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) back on its feet in Dublin.

And that’s how Casement first got into trouble. He was not an IRB member. He was tolerated, certainly, but not trusted by Clarke and his confederates.

“Casement was not a member of the IRB,” Geraldine Plunkett wrote, “because of a scruple he had about oaths; having taken the oath of allegiance for the British diplomatic service, he did not think it right to take the IRB oath on top of that.”

This must have infuriated the hard-boiled Clarke, a man who had spent years in British dungeons.

Also, Clarke was wary of Casement’s two mentors, Bulmer Hobson and Professor Eoin MacNeill—two of the most pacifist revolutionaries in the history of Ireland. Clarke’s suspicions about MacNeill soon proved to be true. MacNeill arbitrarily countermanded the orders for Easter Sunday maneuvers which resulted in confusion and chaos. The revolution had to be moved to Easter Monday and MacNeill had robbed it of its full impact.

“Casement had come into things national,” Kathleen Clarke, Tom’s widow, recalled in her book "Revolutionary Woman," “and Tom knew very little about him. Naturally, he had no cause to place much confidence in him; and the fact that he had been knighted by England in recognition of services rendered made Tom suspicious of him. Casement was not long enough in nationalist things in this country to prove his genuineness.”

With the outbreak of the First World War, Casement ran off to America and then Germany (via Norway) trying to win the Germans over to the Irish cause. In New York John Devoy, the tough old Fenian—Pearse called him “the greatest of the Fenians”—and close friend of Clarke’s, cast a suspicious eye on Casement.

But unlike Clarke, Devoy actually took a liking to him. In his autobiography "Recollections of an Irish Rebel," Devoy saw his strengths and weaknesses.

“While a highly intellectual man, Casement was very emotional and as trustful as a child,” Devoy wrote.

“Practical politics he did not understand … He was an idealist, absolutely without personal ambition, ready to sacrifice his interests and his life for the cause he had at heart but was too sensitive about the consequences to others of his actions.”

Although Devoy had reservations about Casement’s political naïveté, he did supply him with money and shared his German contacts with him. Casement had grand plans for a German landing of troops to coincide with the Rising, but, according to Geraldine Plunkett, “The Germans had had doubts of Casement’s credentials and distrusted his temperament.”

It was during their time together in Germany that Joe Plunkett got to know Casement better. Plunkett was also in consultation with the Germans in Berlin, but he had no hope for Casement’s quixotic plans. It was during this period that Plunkett realized Casement entertained delusions of grandeur.

According to Geraldine, “Joe said that Casement thought he was to be the military leader in command of the Rising and that every one of these things would be a disaster—it was far too late to re-cast plans, Casement was no leader and he could not be concealed at all.”

While in Germany, Casement tried unsuccessfully to raise an Irish Brigade from Irish prisoners-of-war taken by the Germans. He also negotiated successfully the transfer of weapons that were to be used in the Rising.

Although initially against the Rising, he traveled to Ireland in a German U-boat and was captured as he landed on Banna Strand in County Kerry. His German arms, aboard the Aud Norge, were also intercepted by the Royal Navy forcing her captain to scuttle her. It was a double disaster and Casement was moved to London for trial.

His three-day trial took place at the Old Bailey between June 26 and 29. He was prosecuted by Edward Carson, the Orange bigot, who years earlier had hounded Oscar Wilde into prison. He was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death by rope.

From the dock Casement spoke: “Where all your rights become only an accumulated wrong; where men must beg with bated breath for leave to subsist in their own land, to think their own thoughts, to sing their own songs, to garner the fruit of their own labours—and even while they beg to see these things inexorably withdrawn from them—then surely it is a braver, a saner, and a truer thing to be a rebel in act and deed against such circumstances as this than tamely to accept it as the natural lot of men.”

Calls for mercy were heard from the likes of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, George Bernard Shaw, and W.B. Yeats. Conveniently, the British revealed that Casement had written what became known as “The Black Diaries.” Supposedly, they told of Casement’s homosexual romps on two continents. (John Devoy called them “…foul and slanderous propaganda….”)

This quieted the calls for leniency and Casement was hanged in Pentonville prison on August 3, 1916. On the last day of his life, he converted to Catholicism. He became the last of the 1916 rebels to be executed and only one to be executed outside of Ireland.

To this day, his Black Diaries remain controversial. Many believe that they are a forgery of the British Secret Service. Adding to the mystery, Michael Collins, in 1922, viewed them and claiming that he knew Casement’s handwriting—although they apparently never met—and authenticated them.

In 1965 his remains were removed from Pentonville Prison and returned to Ireland. He was given a state funeral, attended by the last surviving commandant of the Easter Rising, President Eamon de Valera, and was buried in front of the appropriately named Republican Plot in Glasnevin Cemetery, the resting place to some of Ireland’s most famous patriots.

He remains one of Ireland’s most enigmatic figures and controversy still swirls around the mere mention of his name. The poet Yeats perhaps said it best, that even today, “The ghost of Roger Casement/Is beating on the door.”

Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at [email protected]. You can follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook here.

*Originally published in August 2016, updated in August 2025.

Comments