An Irish emigrant's rags-to-riches tales and a memoir that provides insight into anti-colonial and anti-Anglo-Protestant sentiments shaped by his experiences.

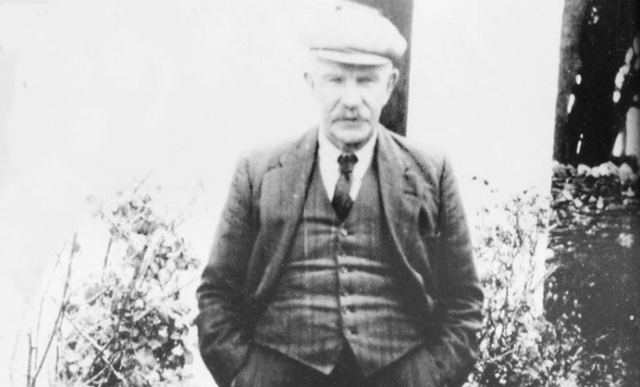

Micí Mac Gabhann was born in County Donegal, in 1865, to parents Thomas Mac Gabhann and Bridget Cannon. They were a primarily Gaeilge speaking family. At a young age, Mac Gabhann moved to Scotland to work on a potato farm before moving to the United States, in the 1880s.

In the United States, he worked in Montana's mines during the government's expansion in the American West. His work patterns resemble that of many Irish immigrants during the mid-to-late 19th century, who was prompted to move to the west due to their roles in the military, railroad companies, or their search for individual fortune.

The federal government's imperial ambition ensured that American forces and colonial settlers were involved in several bloody conflicts and wars with indigenous peoples. Irish Catholics were often the foot soldiers of this expansion, so they engaged in atrocities such as the Washita Massacre of 1868 and the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890.

Read more: How a Donegal "fighting" priest took on his parishioner's landlords

General Thomas Francis Meagher, the former Irish revolutionary, turned Acting Governor of Montana, called for a five-hundred-man militia to, "wipe out the rascally red skins" in 1866.

Moreover, Irishmen like Marcus Daly and Thomas C. Power made fortunes by extracting raw materials from indigenous lands to feed growing industrial metropoles on the East Coast.

After working in the mines, Mac Gabhann followed in the footsteps of over 100,000 prospectors by moving to Klondike during the gold rush. It was here where the Irishman struck enough gold to buy a farmhouse in Gortahork, County Donegal.

Yet, Mac Gabhann's story is not just a rags-to-riches tale of an Irish immigrant who made a fortune and moved back home. His story is unique because of his posthumously published memoir, Rotha Mór an tSaoil. This memoir offers insight into his anti-colonial and anti-Anglo-Protestant sentiments shaped by his lived experiences.

In Montana, Mac Gabhann found himself at the heart of the American eradication of indigenous populations. He witnessed the plight of bands of the Salish, Kootenai, and Siksikaitsitapi peoples firsthand.

Historians have often suggested it was hard to find sources of "westerners" or "pioneers" who were sympathetic to Native Americans. Still, Mac Gabhann's memoir demonstrates that some Irish immigrants saw connections between their experiences and those of the Indigenous nations. He argued that there was "no peace and comfort" for Indigenous peoples under American imperialism because their way of life was constantly uprooted.

Mac Gabhann believed that the forceful removal of Native Americans from their land mirrored the British's merciless eviction of Irish Catholics from their ancestral homes. He lamented that the government encouraged Native Americans to cultivate the earth, but then removed them from their farms. In his view, Native communities started, "work on the rough ground around them until they would turn it into a fine rich field," but their labor was often undone by "some greedy white man."

He expressed anger and frustration at this land displacement because "the same thing had happened to ourselves back home in Ireland." Thus, he believed the Trail of Tears and the continued brutality of the American government were similar to the Land War of 1870s Ireland. For Mac Gabhann, these policies were an extension of Anglophone imperialism.

Mac Gabhann regularly received the news of the hundreds of battles fought against Native Americans. He specifically remembered stories from old-timers about the Battle of Little Bighorn and George Armstrong Custer. Yet, the violence made him more sympathetic to the victims of Anglo imperialism. He stated, "the Indians that were left here... were in a bad way," and his fellow Irishmen "had a great deal of pity for them." He was aware that the Irish were playing a role in "interfering with them" and often linked their oppression with Ireland's colonial experiences. His memoir did not always condemn Native American violence or retaliation for white encroachment on their land. In fact, he suggested that "at least some of us sensed that if they were wild itself, it was not without cause." In other words, the Native Americans had a right to violent revolt because they were facing a foreign imperial power.

He further connected the cultural destruction of Ireland to that of Indigenous North America. He argued that Native Americans wanted to maintain their "attachment to the land of their ancestors" and "keep their customs and habits without interference from the white man."

Read more: Some Irish treasure discoveries that you didn’t know about

This mirrored his own experiences as a Gaeilge speaking Catholic whose dream was to make enough money to buy land in his native Donegal. Mac Gabhann, like many Native Americans, sought to maintain his culture, religion, and language against an Anglo-Saxon colonial onslaught.

Indeed, many historians have demonstrated that writers often narrate about others as a lens to focus on their own struggles.

In Rotha Mór an tSaoil, indigenous peoples welcome the Irish as if they were their "own neighbors." He portrays native women and houses as similar to Irish women and homes. His story is narrated in a way that allows Montana to become Donegal and the native plight to become the Irish struggle.

Yet, Mac Gabhann often makes fascinating points about their joint colonial struggle and a common enemy in the form of Anglo-Saxon "civilization." Many Irishmen suggested that "the Anglo-Saxon policy of dealing with dependent races was ever that of extermination" in Ireland and America.

They argued, "the Anglo-Saxon may have been a colonizer... [but] he was never a civilizer." This fear of cultural and physical destruction was grounded in reality. It was around this time that the London Times is said to have gleefully declared that a Celt, "will be as rare in Connemara as is the Red Indian on the shores of Manhattan."

In November 1948, Mac Gabhann died in his native Donegal, merely months after the passage of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948, which decreed 26 out of 32 Irish counties as an official republic and removed any remaining statutory role of the British monarchy.

His memoir was published in his native language ten years later by his folklorist son-in-law, Seán Ó hEochaidh. It was translated into English by Valentin Iremonger as The Hard Road to Klondike.

His life and works provide insight into the transatlantic feelings of solidarity that some Irishmen felt with Indigenous Americans. He demonstrates how the Irish played a role in the displacement of Native Americans but often felt a kinship between their struggles.

Undoubtedly, Mac Gabhann's vision for a Gaelic Ireland and his sympathy for Native American causes have still gone unfulfilled today.

Read more: Fall in love with the wild and wonderful County Donegal

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments