On December 10, 1791, the Hive, a ship carrying Irish convicts, ran aground just outside of Sydney, Australia.

The wreck of the convict transport Hive was found on the south coast of New South Wales, Australia in 1994. The vessel was transporting 250 Irish convicts to Australia when it was shipwrecked in Jervis Bay in 1835.

Babette Smith's "The Luck of the Irish: How a Shipload of Convicts Survived the Wreck of the Hive to Make a New Life in Australia" tells the story of the surviving Irish prisoners.

The Hive was built in 1820 in England at Deptford (now part of London) and first sailed to Australia in 1834 with 250 male prisoners.

On August 24, 1835, the Hive departed for Australia after picking up prisoners in Dublin and Cork. On December 10, 1835, the ship ran aground on a sandy beach just short of Sydney.

Local people, including Aboriginal people from Wreck Bay and Alexander Berry, helped to rescue over 300 of those on board, including passengers, soldiers, crew and 250 Irish convicts. When word of the wreck reached Sydney, rescue ships were sent to pick up the vessel’s passengers and cargo.

A boatswain drowned in the surf while trying to rescue a young crew member. It would be the only death that occurred during the event.

According to the New South Wales Government's Environment and Heritage website, the incident contributed to naming the bight Wreck Bay.

The Illawarra Mercury published an edited excerpt from Smith’s book describing the wreck and the rescue of the passengers and cargo: “After a voyage of 109 days, across 13,000 miles of ocean, with Sydney Town only a day's sail away, the convict ship Hive was beached.

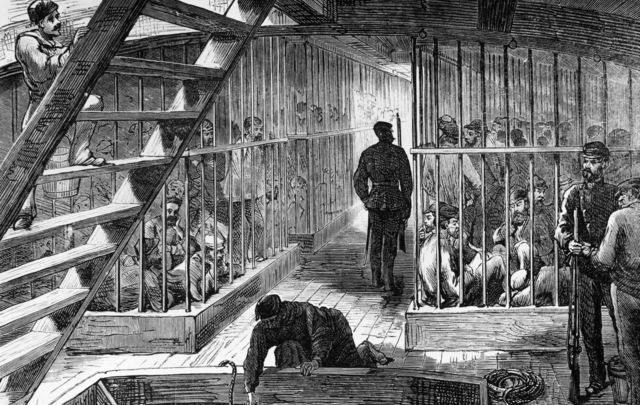

“To that point, it was just an ordinary night at sea. Two hundred and fifty Irishmen were locked, as usual, in their prison deck. Their guard, numbering 29 soldiers from the 28th Regiment, were mostly relaxing below, a lucky few with their wives and children. The commander of the guard, 25-year-old Lieutenant Edward Lugard, was in his cabin. The surgeon Dr. Anthony Donoghoe was busy updating documents he must hand to officials in Sydney. It had been an uneventful voyage: no extreme weather; no attempted mutinies; few people seeking medical attention and those just as likely to be soldiers as prisoners.

“The master, Captain John Thomas Nutting, was also below, indulging in some mysterious activity that later evidence suggests was linked to the contents of a bottle.

“In this relaxed atmosphere, the shock of running aground was magnified. "The confusion and terror that prevailed at this time is not to be described," wrote one of the passengers. Women screamed and kept screaming. Children wailed in fright.

“On the prison deck, men, at risk of death, yelled and swore mutiny if they were not released,” Smith writes of the night of December 10, 1835.

“Confusion below was matched by confusion and strife above. When land was sighted earlier in the day, chief officer Edward Canney had warned the captain that the course he was setting from Montagu Island might bring them too close in during the night.

“Captain Nutting, who had been out in his reckoning several times during the voyage, resented Canney's advice. "Mind your own business. One person is sufficient to navigate the ship," he snapped.

“When third mate Thomas Morgan took over for the night watch, Canney again expressed concern but the captain was insistent. After posting lookouts, he ordered the ship be kept under full sail, then retired to his stateroom.

“Canney too went below but he remained uneasy. Shortly before 10 pm, an alarmed Morgan hurried to Canney's cabin, blurting out dire news: "There's something white on the port bow. It looks like breakers."

“Canney rushed on deck yelling, "Hard-a-port!" On a vessel like the Hive, this would turn her to starboard, away to clear water. But it was too late to maneuver. Under full sail and carried forward by the swell, the Hive began running through sand. As she started to wedge, Canney's attempt to swing her round created a hard jolt that shocked everyone on board into realizing something was wrong.

“By the time Captain Nutting appeared on deck, Canney had ordered the topsail furled and the mainyards back. The master was furious. "Who the hell ordered the foretop clued-up?" he demanded. "I did, sir. I was trying to make her turn off," Canney replied. When Nutting countermanded what he had done, Canney forced the issue by asking formally for orders. But the master suddenly tired of the argument. "Do what you think best," he shrugged. Canney organized the crew to furl all sails fore and aft, heave the spars overboard and clear the longboat ready for hoisting.

“It was at first light that Canney reported to Nutting that the longboat was ready for launching. To his dismay the captain instead ordered the small jolly boat should be lowered from the starboard quarter, the side of the ship that was being lashed by surf. Canney had no choice but to obey. Unable to convince the captain to lower the longboat, Canney chose to join Ensign Kelly and one of the experienced hands on the jolly.

“Predictably, as soon as she touched water, she capsized and was smashed against the ship. Flung into the surf, Canney managed to grab hold of a rope thrown him. Simultaneously, however, he realized that Kelly, dressed in the heavy red uniform of the British army, was in danger of drowning. Canney somehow got the rope round Kelly and had him hauled on deck, saving his life.

“Meanwhile the third man had surfed to the beach by clinging to the upturned boat. Edward Canney then followed him ashore with the hawser line, which he made fast on land before returning to the Hive.

“Back on board, he found the captain intended that everyone make their way individually through the surf by clinging to the hawser. Again Canney remonstrated, proposing the longboat as a safer way to get them to the beach. One observer estimated that at least half the 300 people would have drowned if Nutting's plan had been allowed to stand.

“When the captain peremptorily refused to use the longboat, Dr Donoghoe intervened.

“With the formal support of Edward Lugard as commander of the guard, the surgeon deposed Captain Nutting and gave organizational control to Canney, who accepted.

“Near dawn, they finally got the longboat clear and hoisted out. Her first load was women and children accompanied by some of the guard. Just descending from the ship into the boat was a challenge for the passengers. Very likely some were slung over the shoulders of experienced seamen.

“Next they must successfully ride the surf to shore in conditions none had encountered before. Even with the bigger boat, there was a risk of capsizing. Determined to avoid a tragedy, it seems Canney personally escorted each boatload to the beach. On the deck of the Hive, Henry Lugard watched with admiration: "Thus with almost indescribable difficulties, up to his neck in water all the time, did Mr Edward Canney safely land and save the lives of 300 men, women and children without one single accident," he wrote.

Smith writes of the site that greeted the wrecked passengers as dawn approached: “As the first beams of the sun rose out of the ocean, the Hive's passengers could see they were in a wide bay. The ship had grounded "south of Jervis Bay in a deep bight between Cape St George (to the north) and Sussex Haven".

“Daylight also revealed that the Hive was no more than her own length—120 feet—from shore with about four to five feet depth around her. At low tide it would be possible to wade out.

“They had only the vaguest idea of where they were. "A day's sail from Sydney" was no help when confronted with a vast scrubby wilderness. What lay in between and how were they going to get there? The answer appeared, walking along the beach towards them.

“Emerging at sunrise from their settlement at the northern end of the bay, the indigenous people must have been shocked to find over 300 men, women and children milling around on their land. But over nearly 50 years, even in the remote Booderee bush, they had become used to Europeans and their strange habits.

“They approached in friendship, offering help.

“The Europeans would have been frightened when they first saw the Aborigines - as well as carrying their nets, they had spears for fishing. Soldiers reached for their muskets. Fortunately, Edward Lugard held his nerve until the goodwill of the indigenous people became obvious.

“By sign language and broken English they offered to guide someone to the nearest European who, their gestures indicated, was "up the hill." There was no way of estimating how far that meant. As the most junior officer, Ensign Waldron Kelly was again given the hard job.

“It was 8.30 am when Kelly set out. Approximately two hours later he was at Erowal, the farm of John Lamb Esquire, which spanned the ridge between St George's Basin and Jervis Bay.

“Captain Lamb took Kelly another 15 miles north to an estate named Coolangatta on the banks of the Shoalhaven River. It was owned by Alexander Berry, one of the most prominent settlers in the colony. Lamb and Kelly reached it at 8 pm, almost exactly 12 hours after Kelly set out.

“Berry knew the south coast well. He cross-examined the ensign until he was confident he understood exactly where the ship lay. While Kelly slept, Berry wrote to the colonial secretary, Alexander Macleay, giving more precise directions and warning that the Hive was "in a situation of great danger and most likely ... will go to pieces in the first southerly gale". He had been particularly alarmed to learn some previously secret information: the Hive was carrying treasure. £40,000 in coin was the figure Berry quoted, although official documents state it was £10,000. To Berry's horror, it seemed to have been overlooked and was still afloat in the hold of the Hive.

“News that the Hive was wrecked caused a sensation in Sydney. The press were competing for every last detail and anxious residents devoured everything the papers could tell them. On Monday morning, December 14, the Sydney Herald reported, "Orders were immediately given to despatch HM brig Zebra and the Revenue Cutter to the assistance of the unfortunate people on board. In the course of the afternoon yesterday, the Tamar steam-packet was sent on the same errand."

“Five days later the Tamar was back carrying four soldiers of the 28th, eight women, 11 children and 106 prisoners.

“On January 7, Alexander Berry's schooner Edward brought in the remainder of the stores, the ship's crew of 28 and Captain Nutting. Within days, Nutting had persuaded the enterprising local owner of a schooner called the Blackbird to help salvage what was left of the Hive.

“On January 25 the Herald reported the farce that ensued.

'The Blackbird's boats made 22 trips ferrying goods to the shore. Then the wind changed. That night a strong southerly turned into a violent gale. The Blackbird started to drift. Not even a second anchor would hold her as she began to drive towards the shore. Everything that had been carefully loaded during the day was now thrown overboard and full sails ordered up. After striking the sand several times, she 'carried up high on the beach,' out of danger.'"

For more information on "The Luck of the Irish," visit the Amazon page here

*Originally published in December 2022. Updated in November 2023.

Do you know of any stories of when Irish convicts were transported to Australia? Share in the comments

Comments