175 years ago, on July 29, 1848, the news in Ireland changed from famine to rebellion, albeit briefly. The short-lived Young Ireland rebellion saw rebels captured and imprisoned while others escaped to America.

The Young Ireland movement wanted "an Irish nation that appealed to both Catholics and Protestants, men and women, landlords and artisans," says Professor Christine Kinealy in her book "Repeal and Revolution, 1848 in Ireland."

They failed in their endeavors but successfully captured the world's attention when leaders were tried in court; their sentences were commuted from death to transportation due to a global outcry.

With the help of his aunt Bridget Kelly, John Blake Dillon was one of the men who evaded capture in 1848, making his way safely to America dressed as a priest. So good was Dillon's disguise that fellow Young Irelander, Pat Smyth, traveling with him on the same ship, wondered why this priest stared at him.

When Dillon's first cousin, Mary Anne Kelly, shared this story with Kevin Izod O'Doherty, their political and personal passions had long since merged.

Mary Anne was, by this time, an established poet. According to Kinealy, Charles Gavin Duffy, editor of The Nation, regarded her poetry, and those of Ellen Mary Downing from Cork, and Jane Francesca Elgee, Oscar Wilde's mother, as "some of the most original and popular," collectively calling these female poets, "The Three Graces."

Their poems were published under pseudonyms: Downing was Mary, Elgee was Speranza, and Mary Anne Kelly became Eva of The Nation. Together, they "mined Irish history for inspiration," says James Quinn, author of "Young Ireland and the Writing of Irish History."

Killeen House Courtesy of current owner, Haske Knippels Photographer Loretto Leary

The Kelly family were wealthy Catholic landowners in Killeen, County Galway, about four miles west of Portumna. The Kellys, it would seem, were a nationalistic family.

Mary Anne, born February 15, 1830, spent part of her youth with her grandparents, John and Mary O'Flaherty, in Caherlistrane's Lisdonagh House. The O'Flahertys supported Irish independence—their influence is evident in Mary Anne's poetry.

In 1845, at the urging of her mother and sister, 15-year-old Mary Anne sent her first poem, “The Banshee,” to The Nation, a nationalistic newspaper founded by Thomas Davis and Dillon.

"When the soft maiden of Killeen opened her mouth," says Thomas Keneally in his book, “The Great Shame,” "fire came forth."

Mary Anne visited Dublin with her aunt in 1848. Upon arrival, she discovered that the Young Irelanders, including her editor, Duffy, were either imprisoned or on the run for the failed rebellion at Ballingarry, County Tipperary. Having outmaneuvered the authorities, her cousin, Dillon, was already on his way across the country to Killeen while others awaited trial for sedition under the Treason/Felony Act.

Later, Mary Anne recounted Dillion's presence as a fugitive at the house in Killeen. "He had only gone off a short time when we were that night invaded by police and the magistrate. Our house was ransacked from top to bottom."

When Mary Anne Kelly met Kevin Izod O'Doherty for the first time, he was a prisoner. According to a prison ship's description, O'Doherty, a 24-year-old medical assistant and lawyer's son, was "nearly six feet tall, fresh complexioned, with brown hair and whiskers." Mary Anne, his match in height at 5 foot 11 inches, had, according to a later description by Smyth, "daydreamy eyes and wonderful black hair reaching to her knees." Eva of the Nation and Kevin Izod O'Doherty were a handsome couple.

O'Doherty's lawyer, Isacc Butt, argued during the trial that attending to the sick in fever sheds had shocked the young man's nerves. O'Doherty, looking ill, seemed to gain some sympathy from the jury. Despite an offer of a lessened sentence if he pleaded guilty, Mary Anne's promise of faithfulness convinced O'Doherty to stick to his principles. He pleaded not guilty. Upon being tried a third time, a verdict was reached. O'Doherty and John Martin were sentenced to 10 years in Tasmania, then known as Van Diemen's Land.

On the morning of June 16, 1849, after passing many notes between the imprisoned Young Irelanders, Mary Anne's frequent visits to her beloved O'Doherty, along with Martin and Duffy in Richmond Prison, ended abruptly.

Keneally paints a hastened, bleak departure. "O'Doherty and Martin were roused at five o'clock…given an hour to pack and say goodbye and without a chance for O'Doherty to scribble something to Eva, taken at the gallop across town attended 'by a nearly complete regiment of dragoons' and put aboard a warship, The Trident, for Cork."

From there, The Mount Stewart Elphinstone convict ship delivered him to Sydney, where he boarded the Emma, arriving in Hobart, Tasmania, on October 31, 1849, over ten thousand miles from Mary Anne.

Over the next six years, Mary Anne wrote to O'Doherty, Martin, and Thomas Francis Meagher with news from Ireland—she was, for some time, his only connection due to a divide between O'Doherty's political ideals and his family's. He informed William Smith O'Brien in May 1850 that he still had not heard from his family. O'Doherty remained true to Mary Anne, earning him the nickname Saint Kevin.

On August 23, 1855, having covertly entered Ireland and then England, O'Doherty and Mary Anne wed at Moorfield Chapel with her father, Edward Kelly, and O'Doherty's uncle George in attendance. From there, the newlyweds moved to Paris, which, according to Keneally, "was a shared exile" with John Martin, with whom she formed a lasting friendship.

The O'Dohertys moved back to Ireland, living clandestinely with Kevin's mother when their first child, William, was born in March 1857. Around this time, an unconditional pardon for O'Brien, long considered the leader of the Young Ireland Rebellion, Martin and O'Doherty, was announced.

The harsh reality of Victorian female existence hit Mary Anne in 1858 when, paradoxically, the O'Dohertys could live openly in Ireland, and her husband's star was rising. She was back in Killeen when a second son, Edward, was born on August 2, and O'Doherty was now practicing medicine in Dublin.

Writing to John Martin, Mary Anne confessed, "I have many tormenting troubles of the mean and earthy sort."

A third son was born in 1859, Vincent. She was pregnant with her fourth son, Kevin, when the family returned to Australia in 1860. By 1862, the family had settled in Brisbane.

Misfortune would plague the O'Dohertys concerning their offspring. Within two years, Mary Anne witnessed the death of two children, a baby boy in 1862 and a baby girl in 1864. In 1890, Vincent, the fourth-born son, died in a street accident, run down by a horse-drawn carriage, followed by the death of their 4-year-old granddaughter in 1892. In 1900, two sons died, Edward in an accident and Kevin of pneumonia. Only their daughter Gertrude survived.

The O'Dohertys were initially successful in Australia upon their return in 1860. Kevin O'Doherty was elected as the candidate for North Brisbane for the Queensland Legislate Assembly in 1867. He was already an esteemed and established leading surgeon, elected to the Brisbane Volunteer Rifle Corps, and, as per Keneally, "had no problem doing what Eva (Mary Anne) avoided: drinking the Loyal Toast."

Mary Anne continued to write poetry; her work appeared in The United Irishman, The Irish Felon, The Irish Man, and Sydney Freeman's Journal.

In 1877, when Kevin O'Doherty was promoting another Health Bill in the Queensland Parliament, she was in San Francisco, accompanied by her sons William, on his way to study dentistry in Philadelphia, and Edward, who would study medicine in Dublin. The San Francisco Chronicle announced the arrival of Eva of the Nation.

She dedicated her volume of poetry published in America that year, "To the memory of John Mitchel and John Martin, "felons" of 1848." This posthumous dedication came two years after both men died.

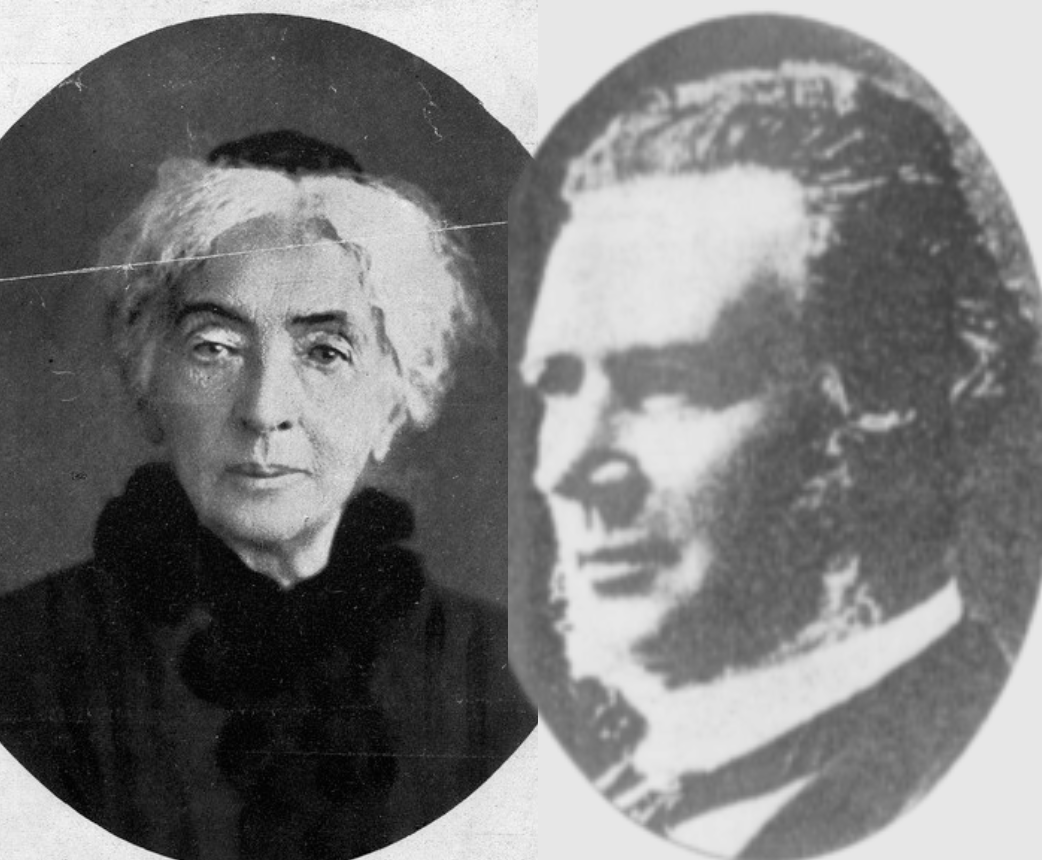

The O'Doherty's in later years John Oxley, State Library of Queensland Public Domain

In the words of Frederick Douglass, Mitchel "was a traitor to humanity" and remains one of Young Ireland's most controversial members—a racist who supported slavery with the argument that government should not interfere with private property ownership. In later years, Mary Anne recalled, "No rising. No plans or order – no leader," believing that when Mitchel was brought through the streets of Dublin as a convicted felon, "The people then ready were filled with rage and enthusiasm." Her support of Mitchel as the martyr hero remained unwavering even in later years, despite his flaws.

In 1879, the O'Dohertys were present in the House of Commons for the reading of Charles Stewart Parnell's Home Rule Bill, which was defeated—this, fueled by the irony that 37 years earlier, Queen Victoria granted the island province of Tasmania (Van Diemen's Land) a degree of self-governance, cemented Mary Anne's nationalism.

Timothy Egan, author of “The Immortal Irishman, The Irish Revolutionary Who Became an American Hero,” aptly captures the O'Dohertys’ indignation. "A paroled rapist, trailing sheep on a Tasmanian bluff, had more political rights than a law-abiding citizen of Erin."

In 1885, Kevin O'Doherty, now living in Ireland with Mary Anne, was elected as the Irish Parliamentary MP for North Meath in the House of Commons. The climate of Ireland did not suit him; he did not seek reelection, and the O'Dohertys left Ireland, returning to Brisbane, Australia.

Their connection with Parnell and Home Rule tarnished the couple's reputation. The Brisbane Courier scoffed, "Doctor O'Doherty is presently, 'starring it' in the Emerald Isle, … he is reaping not unpleasant remarks for the little indiscretions of his hot youth."

The persistent critiques of the Brisbane Courier and the Brisbane Telegraph would destroy O'Doherty's medical practice and leave the family financially strapped. Mary Anne said O'Doherty's support of Parnell "was a very losing game for a professional man, but the good doctor was not one to count the cost."

The couple was more than likely aware of the Woodford Evictions, just over seven miles from her homeplace in Killeen, where, according to the Illustrated London News on January 15, 1887, "tenants of Lord Clanricarde's estate there have been at war with his Lordship s agents and with the officers of the law since last August."

The Home Rule battles continued to rage until December 6, 1922, when the Irish Free State was created. Neither of the O'Dohertys would live to see it.

The O'Dohertys’ plain, wood-framed house on stilts in Queensland was far removed from the grand home in Killeen. Kevin became blind, but through the kindness of three young colleagues, he continued to receive payment for medical practice, although he didn't work.

When Kevin died in 1905, aged 81, the Brisbane Courier had changed its opinion of him. "Who knowing such a man as Doctor O'Doherty can link them with the darker crimes of great agitations?"

Five years later, on May 22, 1910, Mary Anne joined him, aged 80. Shortly before her death, in December 1908, her volume of poetry was published in Ireland. The dedication in this extended volume read, "To the Memory of Our Dead."

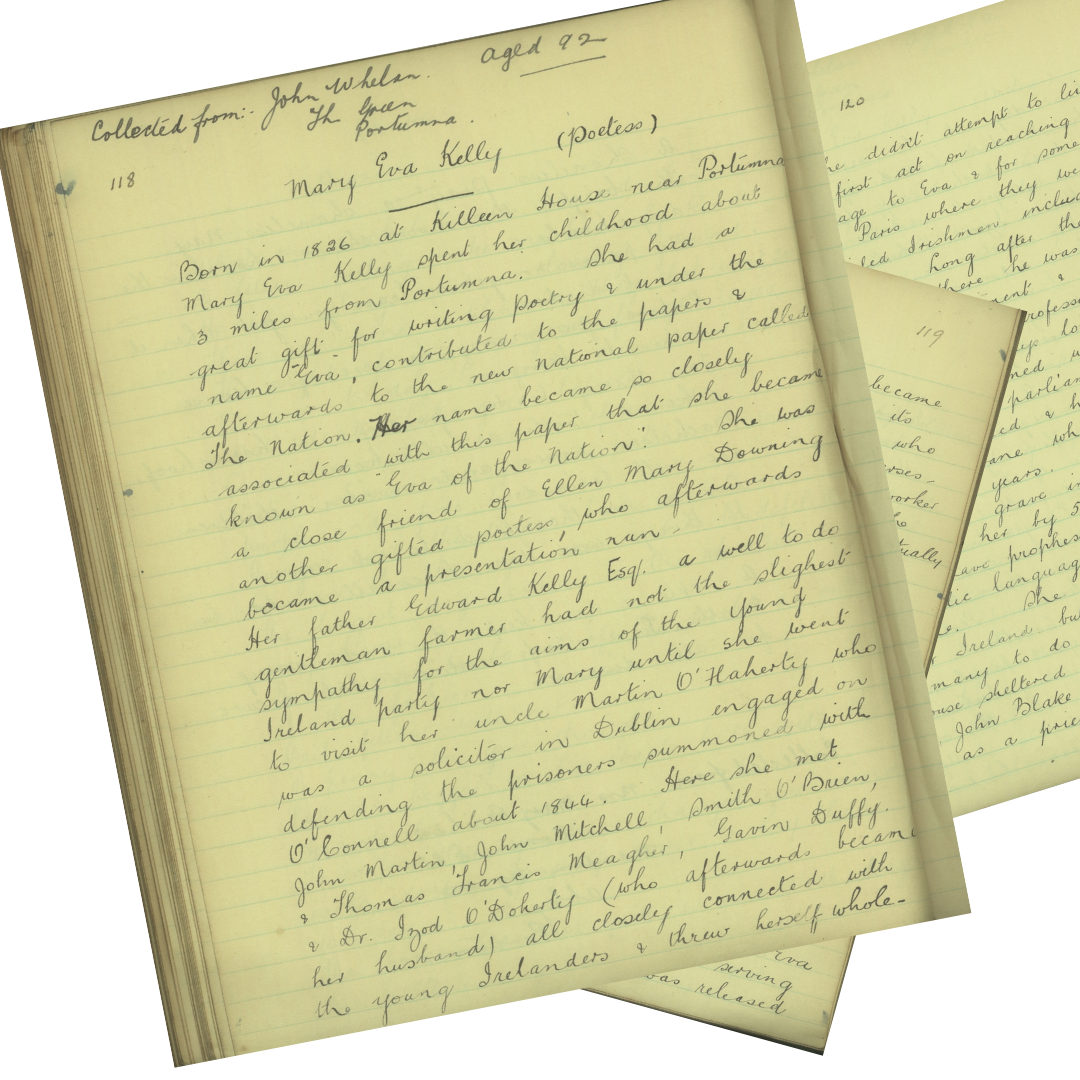

John Whelan, Portumna, Essay National Folklore Collection, The Schools' Collection 57:118-120.

In 1930, the Irish government asked volunteers to transcribe oral histories to prevent the loss of historical knowledge. The project is preserved in a digital archive called Dúchas, which means native.

We learn from a 92-year-old John Whelan of the Green in Portumna, County Galway, that Eva of the Nation's "father Edward Kelly Esq. a well-to-do gentleman farmer had not the slightest sympathy for the aims of the Young Ireland party."

Not all the Kellys shared Mary Anne's nationalistic ideals, and there may have been a rebellion at the house in Killeen.

Kelly's of Killeen Gravestone. Kilcorban Cemetery Photographer William Horrigan

It is now a three-story house, but it was two stories when Mary Anne Kelly sat and put pen to paper, writing poetry and corresponding with her Young Ireland companions. It is in this house that Dillon and O'Doherty took shelter as fugitives. Did a teenage Mary Anne look out her bedroom window, daydreaming and gazing across the fields towards Kilcorban, just a short distance away, where her parents would one day be buried?

Killeen is an Irish word. It means "little church," "burial ground," and "Cillín," a pet name for "O'Ceallach," —a descendant of Kelly. At Kilcorban Cemetery in County Galway, all three meanings come together. In the shade of a small church ruin is the final resting place of Edward and Bridget Kelly, owners of Killeen house.

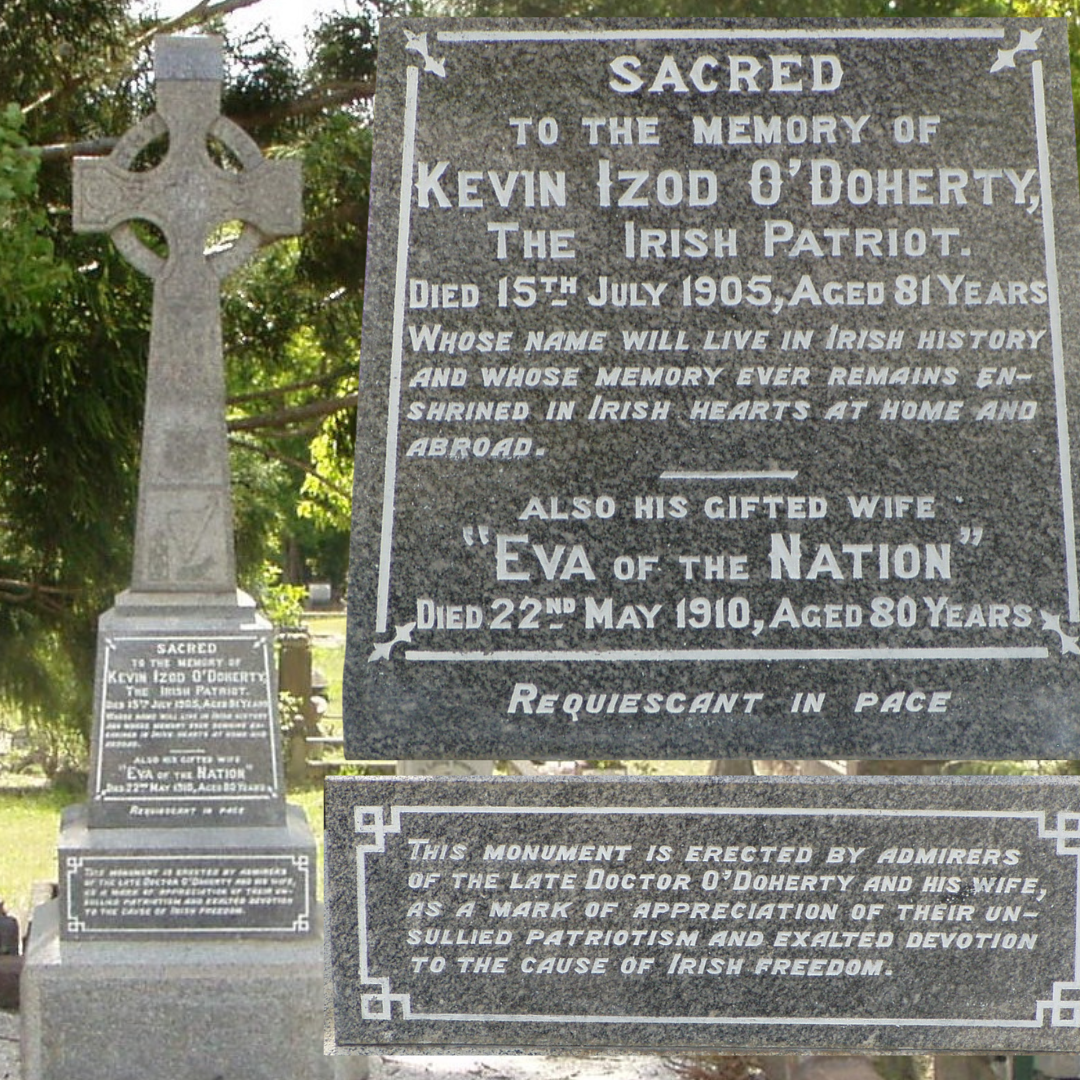

Over ten thousand miles away, their daughter, Mary Anne Kelly, and her husband, Kevin Izod O'Doherty, are buried in Brisbane, Australia, united in death by the symbol that connects both the graves in Kilcorban and Toowong Cemetery, a Celtic cross.

O'Doherty Headstone Monument Australia Photographer Diane Watson

The inscription on the base of the O'Dohertys' gravestone reads, "This monument is erected by the admirers of the late Doctor O'Doherty and his wife as a mark of appreciation for their unsullied patriotism and exalted devotion to the cause of Irish Freedom."

Above it, Mary Anne is memorialized as Kevin Izod O'Doherty's "gifted wife, Eva of The Nation.”

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments