Erne Go Bragh –“Erne Forever."

June 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of the defiant boat protest that launched The Erne Fishery Case, also known as 'The Kildoney Men's Case' (1925-1933), one of Ireland’s most historic legal victories for public fishing rights against the English landlord establishment and the British Empire.

Before Ireland was iconically known as “The Land of Saints and Scholars,” the Emerald Isle, since ancient times, was a fisherman’s paradise - an anglers Eden - “The Land of Farmers and Fishermen."

Indigenous Irish clans and native Gaelic tribes worshiped the holy trinity of the land, sky, and sea through their blessed Celtic spirituality–personified by the Irish land-goddess Ériu and by the sea-god Manannán Mac Lir.

Ériu and Manannán Mac Lir.

Farming and fishing perpetually remained the Irish way of life, even through the era of the saints and scholars, up until Irish farmers and fishermen lost their indigenous rights and freedoms to farm their native meadows and fish their native shores during the English invasion, colonisation, and plantation of Ireland.

While the Kildoney Men’s case officially began on February 15, 1927, the legal proceedings were initiated following the strategic act by six brave Kildoney fishermen on June 3, 1925, to challenge the Erne Fishery Company’s claim to exclusive fishing rights on the Erne Estuary.

One of the Kildoney fishermen’s descendants, Paddy Donagher, who is the proud grandson of Alex Duncan, wrote a history book in 2013 that poetically tells the story of what happened that fateful day:

“On a fine June morning in 1925” as Paddy expressed, the fishermen “pushed their small tar and canvas boat away from the bank of the River Erne.

"As they began to move out into the broad channel, their intention soon became clear. The six fishermen, all from Kildoney, were poachers, and their destination was the tidal estuary of the river, which teemed with salmon. The men were, in fact, doing nothing more than continuing a well-established local tradition.

"However, these fishermen were undoubtedly employing the strangest method of poaching ever seen upon the Erne. Instead of coming in the dead of night with only moonbeams and twinkling stars to guide them, they had launched their boat with the sun high in the sky.

"Rather than making anxious glances over their shoulders with ears tuned for the slightest sound, the men chatted and laughed loudly as they went about their task.

"They were fully aware that an Erne Fishery Company motorboat had recently been seen patrolling in the area, but did not seem in the least bit perturbed.

"Instead of seeking the safety of solitude for their illegal activities, they had brought a large audience along to watch them, an audience that actually included members of the Garda Síochána, Sergeant O’Connor and Garda Dan Linehan. The Mall Quay was lined with onlookers, men and women were seen on both sides of the shore, all seemingly in a very jolly mood.

"Unsurprisingly, this eccentric method of poaching was not to yield a single fish, as not long after the six fishermen had shot their net, the roar of the nearby conservator’s motorboat was heard descending on them.

"Before the fishermen had time to haul their net back in, the motorboat sped towards them and rammed their craft at full speed. The side of the small tar and canvas boat caved in immediately, and as it sank the conservators seized the empty net and hauled it in themselves.

"Having done this, their next task was to haul in the six Kildoney men whose boat was sinking fast, a task which was achieved in spite of the attempted heroics of the injured William Morrow who declined to leave the sinking boat, shouting 'I’ll go down with her.' He, however was hauled into the conservator’s boat.

"When the motorboat dropped the six would-be poachers off at the Mall Quay, the watching crowd descended on them and rewarded the Kildoney men for their strange performance with a rapturous round of applause and cheering."

The launch of this one tar-and-canvas boat launched more than just the boat into the water. The boat also launched a local revolution that turned the tide for fishermen’s rights and fishing freedoms in Ireland. The peaceful nature of the 1925 boat protest that sparked the Erne Fishery Case did not start in the Oireachtas (Ireland’s National Parliament), it began in a humble, whitewashed Kildoney cottage, where six fishermen under a thatched roof warmed their well-weathered, angler hands by a hearth, planning their strategic fight for public fishing rights.

From these six men, another 40 fishermen joined the cause for fishing freedom and were represented by their astute legal team of Frank Gallagher and James Mc Loone.

Eight years later, on July 21, 1933, the fishermen were ultimately victorious against the English landlord establishment and the British Empire. The peaceful boat protest was - literally and symbolically - the rising tide that lifted every fisherman’s boat in Ireland.

Great celebrations followed on the Mall Quay at twilight on August 5, 1933, and Gallagher spoke passionately of their struggle and victory: “By our magnificent fight, we have righted a grievous wrong, a wrong that has root three hundred years and more.

"No longer would native fishermen have to trawl the open ocean for fish in canvas boats while all the river-mouths around the coast were in the hands of foreigners with their spurious fishing rights.”

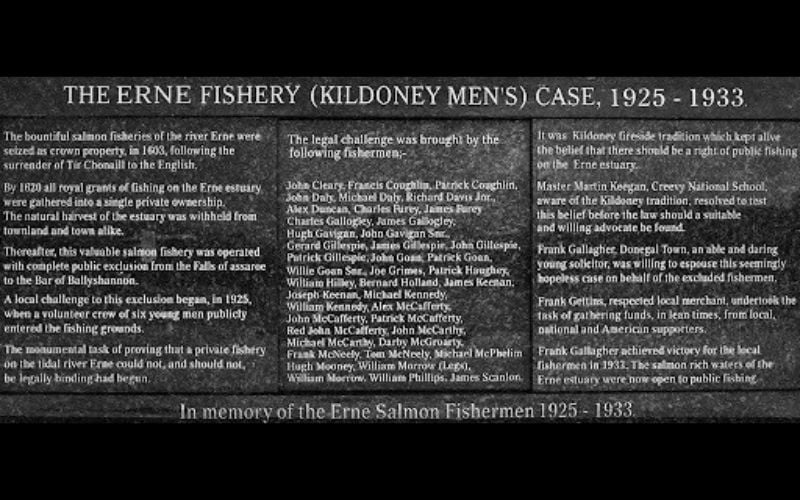

The fishermen are eternally commemorated on the Kildoney Fishermen Memorial at the Mall Quay in Ballyshannon. My own grandad P.J. Patton, a fishing bailiff and inspector of the fisheries, was related to two of those courageous Kildoney fishermen, Mickey McCarthy and John McCarthy.

Many descendants of these historic fishing families proudly live on in the community and are named in Paddy’s book and noted on Where Erne, Drowes, Duff meet the sea. Each family still has their own fishing story to tell of how their ancestors were a part of not just local history, not just Irish history, but world history–fighting for fishing freedom:

100 years later, Gallagher’s stirring speech is still a haunting echo for Irish fishermen. 20 years after Gallagher’s words, the Assaroe Falls, the famous salmon -leap and one of the natural scenic wonders of Ireland on the River Erne in Ballyshannon, was destroyed by the construction of the hydroelectric power station, which had a devastating impact on the salmon fisheries.

Pat McNeely is a proud descendant of two of those Kildoney fishermen. He is the grandson of Francis McNeely and nephew of Thomas McNeely, and expressed that his grandad and uncle "would be turning in their graves to see no fishing on the estuary.

"The Erne fisherman fought to keep the estuary open to local families, but when they built the power station, they made a huge mistake, the fish pass was designed so fish had to dive to find the entrance. Salmon would jump up the falls so they could not find the way up. Most of the Erne salmon ended going up the Moy estuary, and the Erne fishing dried up.

"We lost one of the greatest assets in this area due to so-called progress.”

What has also happened within the past quarter century or so is that those fishing rights that the Kildoney fishermen fought for and won for every Irish fisherman in Ireland have been tragically lost.

This time, it truly hits home for Irish fishermen because it is not an English landlord establishment or the British Empire that took away those indigenous Irish fishing rights–it is their own Irish government in Dublin, controlled by the European Union in Brussels.

I asked well-known Donegal fisherman Seanie Carty, from the proud historic fishing family from Fish Lane in Bundoran, to provide a firsthand perspective into the current state of Irish fishing.

Seanie’s vitally important insight should resonate for Irish fishermen at home and around the world: “The sad reality is that the victory of the Kildoney Men was short-lived.

"In my opinion, there could and should still be a small traditional fishery open there. Even if they could only keep a certain number of 'ranched' fish. The traditional and tourism value alone of this would be immeasurable. If managed correctly, it would still be sustainable. Likewise in the sea.

"It saddens me that my children will not know the thrill of moving along the drift net looking for 'missing floats and then seeing the flash of silver through the water and understanding the importance of this for the survival of previous generations.

"For me sitting here talking to you in 2025, I can say that salmon is ingrained into the DNA of the families that depended on them. My great-grandfather and his cousins ran the commercial salmon fishery on the Drowes back in the 1880s/90s.

"Ever since that, and probably before until the late 1990s, salmon has been an important component of life. Growing up in Fish Lane / in West End Bundoran, I remember during the summer months people coming and going for fish, and even the bath was taken up with salmon.

"After the salmon fishing was closed, there was a fierce sense of loss. It was the same for all the fishing families, and I'm sure Ballyshannon was no different.

"I don't think my father ever put out on the boat again after.”

Seanie then detailed the problems and offered reasonable, common-sense solutions that could be applied to Irish fishing communities: “I see massive potential in a small traditional inshore fishery.

"Fishing is by no means what it once was, but a model based on real sustainability and tourism could be great.

"Back in the 1980s, between Creevy, Bundoran, and Mullaghmore, there would have been around 40 families making a living directly from fishing, while today there are only around six.

"Once the salmon was closed, everyone was forced into fishing mackerel, pollock and crab, and lobster. The big tank boats have done serious harm to the stocks of mackerel and pollock, and to be honest, they are not really worth the effort anymore. That leaves just lobster and crabs.

"In recent years, from September to Januar,y boats have been allowed to "pair trawl in the inshore bays for 'sprat.' The problem here is 1: The mesh size for Spratt is tiny, and 2: The waters of Donegal Bay are shallow, so nothing escapes these nets.

"Between the big 'mostly foreign' boats cleaning the areas that replenish the bays, and the other boats fishing spratt, which by the way is mostly used for fish meal (dog food and the likes), it won't be long until it won't be worth anyone's while going out to sea.

"In recent years, Donegal Bay has been so blessed with huge amounts of bluefin tuna, humpback whales, and other fantastic wildlife. If their feed is allowed to be taken away, then they will leave too.

"The solution, in my opinion again, is a small artisan fishing fleet. Allowed to bring in a few salmon and indeed a few bluefin tuna as well as the lobster and crabs. If the offshore fleets could be better controlled, the mackerel would come back too.

"Fishing for 'fish meal' needs to be stopped. So many families have been spiritually starved by losing the connection to the sea.

"If this style of fishing-tourism model could be established, then many of them might see fit to reconnect, and at the same time, the tradition of making a living from the sea could be saved.

"Sometimes I wonder if the people with shirts and ties that sit around office tables in government buildings are actually trying to find ways to end the independence and freedom of the inshore fisherman and put an end to this way of life.

"If conservation is really the agenda, then surely the obvious place to start would be the boats from all around Europe and further afield that indiscriminately take in hundreds of tonnes at a time from 'Irish waters.'"

While fishermen’s indigenous Irish fishing rights have been tragically washed away by the political tides of time, a traditional musical commemoration organised by Paddy Donagher will be held on August 3 at the Mall Quay in Ballyshannon.

The commemoration celebrates the 100th anniversary of what was once fought for and once won by the Kildoney fishermen - many Irish fishermen still wonder as they cast out their ancient fishing lines from the shores of their imagination - could fishing freedom be caught at a Celtic twilight once more?

*Éamon Ó Caoineachán (Eddie Keenaghan) is a poet, writer and historian, originally from Bundoran, Co Donegal, but now living on the Gulf Coast of Texas. He is currently a PhD postgraduate in Arts at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick.

Comments