The family of Detective Eugene Casey, who was one of the investigators of an infamous 1957 mob murder, was stunned to see him in “The Irishman” movie.

My husband finds it odd, given our 30 years together, that I grew up with a photograph of a Mafia murder scene as part of family lore and family pride. The famous photo is a glossy black and white of a very bloody story, one frequently told by my father during family gatherings.

We have it still, somewhere, in a large envelope, a very tattered copy of the original photo by George Silk, later published in a 1957 LIFE magazine—One of the Century’s Greatest Mafia Hits, Barbershop Rubout of Mob Boss Albert Anastasia, Murder, Inc.’s #1 Killer.

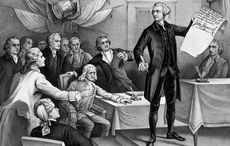

In it, Det. Eugene J. Casey, my very young, very slim father—he was still a smoker then—stands, keenly focused, over the dead body of the notorious Albert Anastasia—known as the “Lord High Executioner” because of the number of homicides he committed. “Da” is sketching the approximate position of Anastasia's bullet-riddled body lying dead on the floor.

Read more: Ed Sheeran related to mafia hitman portrayed in “The Irishman”?

The barbershop clock on the rear wall shows the time at 12:55 p.m. It was a Friday that Oct. 25, 1957, and on that morning, according to my father, the truly “monstrous” Albert Anastasia had been driven from his Fort Lee, New Jersey mansion into Manhattan for his customary appointment at the Grasso Barber Shop on West 55th Street. The barber was located just inside the lobby entrance of the Park Sheraton Hotel on Seventh Avenue. This was Anastasia's undoing, my father advised us, as my brothers and I passed around the photo, careful not to let our sticky fingers leave smudges. It was this very routine his assassins anticipated. As Anastasia settled into the barber's chair, his face wrapped in the soothing warmth of steamy towels in preparation for his shave, two men—their faces covered as well—rushed in, shoved the barber out of the way, and shot Anastasia. After the first round of bullets, Anastasia apparently flailed forward at his killers, mistaking their reflections in the mirror wall of the barbershop.

(My brothers and I loved that part of the story! Later on, we would play “Assassins”—I as Anastasia, reclining in the backyard chaise lounge, beach towels wrapped around my head, my brothers gleefully opening fire on me.)

My father always finished recounting the story the same way, because it always ends the same: the gunmen shooting until Anastasia falls dead on the floor, the hitmen running out the door. No one is ever arrested for the murder.

Whenever Da told the story, we were enthralled—our father had actually been there.

My brothers and I don't get together during the holidays anymore. Too far away is too often the excuse, but we live closer than that, really, and easily could. Perhaps it's so that after the final parent dies, in the case of my brothers and I, it was the second death, the mother, when we finally became what we probably always had been—a distant, yet loving, family. Sentimental but remote, disconnected but loyal.

Full of loss, tenderness, and yesterday's intentions. In a word: Irish.

But this weekend, one brother, the younger one, started a bit of a family reunion when 22 minutes and 44 seconds into watching ”The Irishman,” he was astonished to see our father on the screen, large as life, or as large as his TV screen. I received his first email late that night, Subject: Da's in The Irishman!

I don't often hear from this brother, and when I do, the exclamation points are not always happy ones. At first, I thought he meant that the essence of my father's life as an NYC detective in the 1950s had been captured in Scorsese's opus on violence and secrets. But a phone call soon after, from the older brother, along with the message, "Have you seen it?" confirmed the sighting. By the next morning, my daughter sent me a screenshot of the very screenshot she had seen while watching the movie with her boyfriend.

"Is that my grandfather?" she texted.

Yes.

By the end of the weekend, more family and friends had reached out, amazingly having recognized my father—now in the movies—from the famed family photo. Powerful and poignant tributes to his integrity, kindness and immense talent as an investigator. His determination to get to the truth of a case, his passion for his job. Accolades from his colleagues, in their nineties, most of them now in Florida, who had asked their kids to email us their memories of him.

The photograph, taken by Silk through the plate glass window of the barbershop—which like everything else in NYC is now a Starbucks—is readily available on the internet, no longer a fragile Casey family treasure. Looking at it now, twenty-five years after my father's death, I see it so differently than when I was young. I no longer see just the fat dead body of a terrible monster, a murdered murderer, sprawled lifeless on the bloody tile floor. I only see my Da, a young man, an innocent, really, dispassionately drawing the details of death as a basic part of his job. He is engrossed in his work, intent on the task at hand, seemingly solitary in the midst of an active crime scene.

On October 25, 1957, I was ten months old. I imagine my father early the next morning, exhausted, driving his brand new maroon Chevrolet Impala along the Belt Parkway, finally heading home to Long Island to his sleeping family—far from midtown, far from the barbershop, far from the very bloody mess he had spent the day and night investigating.

How did he square such days and so many others filled with violence and secrets, as he came in the door, setting his heavy ring of keys on the foyer desk, securing his loaded revolver in the far reaches of the hall closet, even though my brothers and I knew exactly where it hidden. Coming home later and later, days into nights, over the next twenty years "on the job." In time, sometimes, not coming home at all, to his beautiful but increasingly bewildered wife, to three complicated children ,the lunacy of mowing a suburban lawn, Little League losses, the need for a new roof, and the tyranny of being on time for Sunday Mass.

Read more: "The Irishman" is the best film of Martin Scorsese's career

Frank "The Irishman" Sheeran. Image: Getty.

All of this as the faraway sirens of violence and secrets sounded in his brain.

This weekend my family was together again, and I was with my family. My brothers and I laughed and cried, and drank as the Irish do, as in calls, and texts and emails we marveled at the gruesome photograph that once held such childhood reverence and awe. And we promised we’d stay in touch.

But the Irishman, my Da, is long gone, and with him, the violence and the secrets of a life spent in crime. Gone, too, and forever gone are his answers to the questions I would only now ask. But one second in a fine film brought him back to me.

For a moment, he was actually there.

Comments