In 1967, aged 11, I was sent to “the Brow," the Christian Brothers School in Derry, Northern Ireland.

The school was perched on the Brow O’ the Hill that overlooked the Bogside, and the gasyard to the rising housing estate of Creggan. It was next to St Columb’s College, the alma mater of such luminaries as Seamus Heaney, the Nobel Prize-winning poet, John Hume, a giant amongst Northern Irish politicians, Brian Friel, the playwright, the “Irish Chekhov," and Phil Coulter, a multi-awarded composer of popular music.

One of Coulter’s most popular songs, “The Town I Loved So Well” deals with the embattled city of our youth, filled with “that damned barbed wire” during the Troubles.

Coulter’s lyrics captured those school days:

In my memory, I will always see, In the early morn the shirt factory horn, But when I returned oh my eyes how they burned,

The town that I have loved so well.

Where our school played ball by the gas yard wall,

And we laughed through the smoke and the smell.

Called the women from Creggan, the Moor and the Bog.

While the men on the dole played a mother’s role.

Fed the children and then walked the dog.

And when times got rough there was just about enough,

But they saw it through without complaining.

To see how a town could be brought to its knees.

By the armoured cars and the bombed-out bars,

And the gas that hangs on to every breeze.

Now the army’s installed by the old gas yard wall,

And the damned barbed wire gets higher and higher,

With their tanks and their guns.

The Troubles were an ever-present backdrop to my life during the late 1960s and the 1970s. A complex conflict from 1968 to 1998 with multiple armed and political actors that included an armed insurgency, principally waged by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), whose aim was the creation of a united independent Ireland. They were confronted by over 30,000+ members of the British Army and the local police force.

Northern Ireland was always seen as a “cold house” for Catholics, in the form of systematic discrimination, in housing, employment, and police enforcement.

The Troubles ignited while I was attending secondary school. The catalyzing event probably occurred on October 5, 1968, in the city where a march had been organized by civil rights campaigners, protesting about discrimination and gerrymandering in Northern Ireland. The marchers were met with a brutal force from the local police, using batons and water cannons.

Coverage of the violence achieved more in terms of highlighting the plight of Northern Ireland’s Catholic minority than decades of dogged, but unproductive, campaigning by nationalist politicians. Derry suddenly became synonymous with Selma and the US Black civil rights struggle, led by the murdered Martin Luther King, on April 4, 1968.

In 1971, after almost a hundred years on the same site, the Christian Brothers moved to a brand new purpose-built school, on Foyle Hill, high above the city in Creggan and the River Foyle, where the school had commanding views of the natural beauty of the place, the river flowing from Strabane, all the way to the North Atlantic sea.

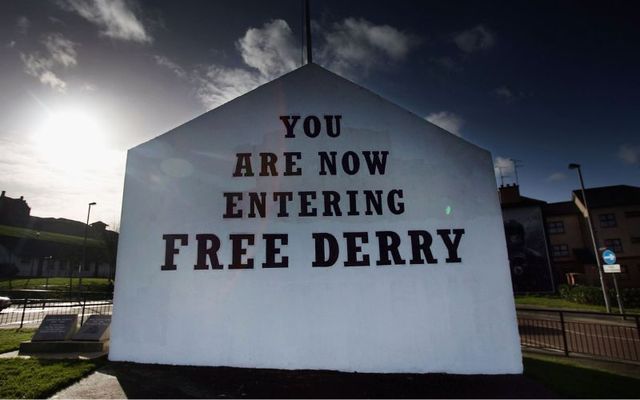

The Creggan and the Bogside were part of “Free Derry," an enclave of the UK that was not policed by the British forces of law and order. A fleet of Ford Cortinas carried the masked and unmasked IRA men, known as “the Boys,” around the streets, including Martin McGuinness, the chief. Locals, tradesmen, students, and teachers passed through checkpoints set up by them. Target practice by the Boys was a regular event in a field overlooked by our school.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

It was mid-1972, maybe it was a Tuesday. “Did you see the soccer last night?”, teacher, Phil McLaughlin asked. The class knew to keep him talking as long as possible to prevent the study of the little red book, the prescribed text for his subject, Business Studies. It was a relaxed class. While we read the next 20 or so pages of the textbook, Phil consumed his latest thriller, a Peter Carey, perhaps. He also consumed Polo mints. A discussion of the text followed.

Outside, in the field, down below we saw “the Boys" having their usual target practice. Big Phil signaled to me to come up to his desk and asked if I could go to the nearby shop to get him some fresh baps, a local name for muffins, for his lunch. I was not the usual local errand boy as he was absent. Phil was my brother-in-law’s brother, such was Derry, being a small town, really.

He handed me a pound note. “Don’t lose me change!” he added as I made my way to the door. Even though I was going on an errand for a teacher, the unwritten law was to avoid the principal, Br Egan or Br Burns, a retired brother, who patrolled the corridors for malingers.

Having got my purchases, I carefully counted the change and placed it in my empty left trouser pocket. Keeping the bap and cream finger in purchased condition was essential. I held the white paper bag containing his lunch very carefully.

Waiting to cross the road to the school, a familiar body wrapped in a large duffle coat stood beside me. From within its huge hood came a grunting salutation. I did not reply. Was that John from my class? The person hid his hands in his pockets.

However, something about the flop of the elbows did not look right. He scurried away towards the school and disappeared up the lane beside the gates. As he ran, I looked at the sleeves of the coat and saw that the sleeves were tucked into his pockets. His arms were not inside the sleeves. Underneath the long coat were two thin rifle barrels poking out, just above his ankles. This was the purpose of his oversized coat.

“What kept you?” The sarcastic question bawled at every boy tasked to get the baps. I never mentioned the boy in the duffle coat. There is a saying in Northern Ireland, “Whatever you say, say nothing.” The ritual was completed with me getting a Polo mint as payment. Leaving class for a short period was the better reward, although seeing a familiar-shaped gunman who seemed to know me had been unnerving,

As I returned to my desk, I looked through the windows. There, down below, a group of men, the Boys, had gathered under the hedge. The penny dropped - that duffle coat was moving weapons for their target practice session.

Big Phil had seen them too, and asked us to continue reading our little red books and ignore the dozen men and boys milling around the edge of the field below. It was difficult to do. A couple of them placed targets in the center of the field, a round target and a dummy.

As they shot at the targets, this unreal shooting gallery, through the dirt-smeared windows, captured our full attention. The staccato blasts of their shooting echoed through the sunny morning, indicating that something was amiss. After what seemed quite some time, Big Phil drew us back to his discussion of how business, in a parallel world, could make a profit.

Suddenly, all heads turned to look through the windows to determine the source of a great rumbling outside. It was the whoop-whoop of a helicopter’s blades, flying outside the school’s windows. After hovering over the fields, it rose swiftly, the pilot realizing what was occurring below. The helicopter dipped again, flew at speed over the field, and headed towards us, leaving the windows vibrating in its aftermath.

Big Phil sighed deeply. “Ah, boys! Where were we? Write down your answers and then we’ll start.”

Minutes later, the thundering whirring of three Wessex helicopters came into focus, shattering any pretense of normality. They hovered over the fields, next to the school until, one by one, they disappeared beyond the hedges and rose sharply again. British soldiers had been dropped into the field above. We could see their green garb moving along the upper hedges.

The Boys collected in a bunch by the lower hedge. A stream of shots rang out. A sniper had climbed a tree and let off a volley towards the newly arrived troops, who returned fire, scattering the top leaves of the trees where the Boys positioned themselves.

Two fields and a hedge separated the warring parties. We had a grandstand view of the battle below, all of us now standing and watching through the windows.

Further rattles erupted beneath us, as the British attempted to move forward but the gunmen held their defensive positions. Given our strategic view, we could advise both parties on how to advance.

“Jeeze, boys I guess we better make a move, leave your books," said Big Phil. Just then, a blond-headed and bearded new teacher, Seamas Bray, stuck his head into the room, shouting, “We will evacuate to the Quad, NOW!” Seamas, another brother-in-law!

The evacuation bell rang too, and hundreds of boys filled the corridors and stairs leading down to the Quad, a sanctuary from the gun battle above. It was below the main part of the school. Windows above us shattered as bullets ripped through them.

The Quad housed the metalwork room on one side and the woodwork room on the other. A pond had been sculptured with various plants. As the boys streamed into the safety of the Quad, they trounced everything in sight, the garden pounded by hundreds of tiny feet. The metalwork teacher stood astride, attempting to save the contents of the Quad’s garden. Eventually, we escaped the battle through a side gate that led into a square of houses and down the winding Foyle Hill, to safety.

As hundreds of pupils arrived in the little square outside the school grounds, we found everyone going about their daily business, ignoring the life-and-death battle, five minutes away. This was typical of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

As we walked off, we realized our time was our own for the rest of the day. I went to my mate Liam’s house for a late lunch on the other side of town to plan what to do with our unexpected freedom.

*Hugh Vaughan has written several books with Irish themes. "Borderland," "An Analytic Pub Crawl," "Wanderings and Observations," "Cillefoyle Park," and "A Bump on the Road." Visit his website HMVaughan.com for further details.

*Originally published in November 2023. Updated in May 2025.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments