Anyone who grew up in Ireland in the late 70s has seen David Rooney’s work.

In 1986, his illustrations first appeared in Hot Press Magazine, then The Irish Times, and many other newspapers, delivering a sharp, intelligent, fresh perspective on the turbulent changes in Irish society.

The art came relatively easy to Rooney. Music is a different experience.

“It’s the zone you get into when you are a child," Rooney says. "The person who draws the pictures is the 4-year-old who didn’t know it was getting dark. That’s where the art comes from. Whereas with the music, I have to be more present."

As a child, Rooney preferred staying home painting with his mother to attending an all-boys school.

“I pretended I was in a Japanese prisoner of war camp,” he says, recalling a coping mechanism used to help him deal with the violence he witnessed among students and daily dished out by the Brothers. While attending the Christian Brother’s school in Cork, Rooney recognized he feared the living more than the dead.

During visits to his maternal grandparents in Tuam, Co Galway, Rooney would “sit with the bones” in old tombs in a graveyard near his grandparents’ home and experience calm.

“I had no fear of the skeleton in the tomb,” Rooney says, “but I was terrified of the brother in the school.”

Rooney’s father was a sergeant in the Gardai. The family moved around the country numerous times and, in 1976, ended up in Eyrecourt, Co Galway.

13-year-old Rooney was one of ten other boys, day students, at an all-girls boarding school in Banagher, run by the La Sainte Union nuns—school was now “bliss.” Hobbies came and went, birdwatching and then model making, all pursued “at a near-adult level, but once I arrived in the convent, music, and art took over,” Rooney says.

However, this was Ireland in the late 70s and early 80s, an era Rooney describes as “dark.”

On visits to his father’s homeplace in rural Fermanagh, while kicking a ball along the road, Rooney encountered soldiers “in full camouflage with blackened faces” in the ditches. It was exciting to an innocent child, but Rooney now realizes, “All over rural Ireland, there were soldiers or skeletons in the ditch at some stage.”

David Rooney, his father Joe Rooney, and author/singer/songwriter Declan O'Rourke at the launch of Rooney's Famine Artwork exhibition when it found a permanent home at the Irish Workhouse Center in Portumna, County Galway in August 2022. (Suzanne Bach)

Rooney found a new “obsession” in his teens: music. Hot Press Magazine launched in 1977. Remembering his excitement seeing the magazine for the first time, “Wow, there are other people like me,” Rooney says. Ten years later, his illustrations would feature in it.

Doing editorial work for Hot Press Magazine, The Irish Times, and eventually, his scraperboard work for the BBC documentary, "The Story of Ireland," Rooney had to learn to work quickly.

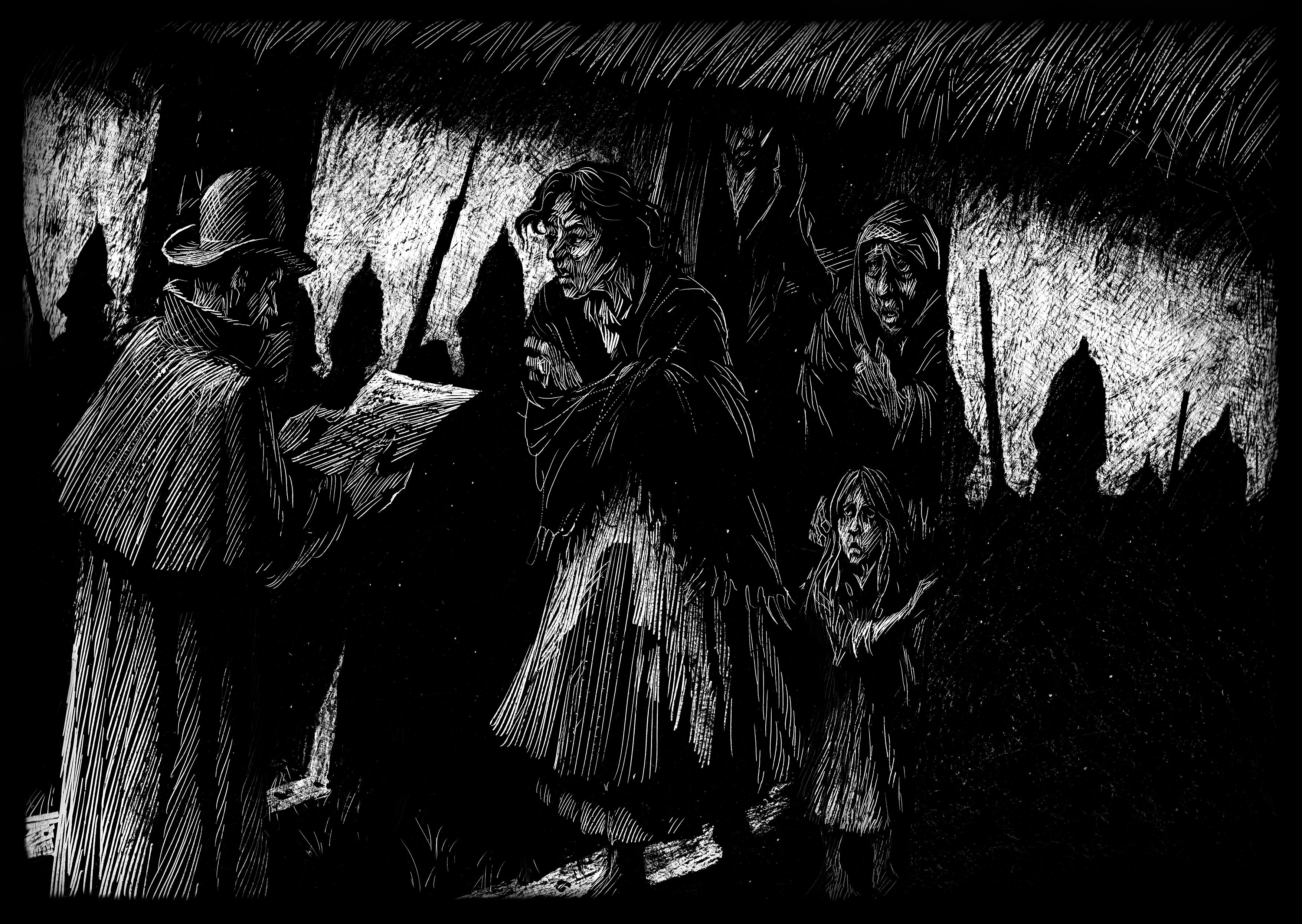

Rooney’s scraperboard technique sounds almost surgical - a scalpel on scraperboard as he scrapes away black to reveal white.

“For every scraperboard piece I’ve done, there is a pencil drawing. Everything is exactly where it is in the final piece,” Rooney says.

However, “The final pieces have a few subtle surprises. There’s still an element of chance, allowing luck to determine how it might turn out.”

Rooney attributes his mother’s love of old black-and-white films to his keen sense of dark and light in his scraperboard art. As a 4-year-old watching those films with his mother, Rooney recalls, “The thrill of the point of view of the camera and the lighting. Now everything I do is lit like that.”

Rooney’s connection to the past and scraperboard art lends itself superbly to showing the simple truth, in black-and-white, of the Irish Famine.

“I’m lucky in that the artwork doesn’t take that much out of me; I just channel it,” Rooney says, recognizing that he has been “massively fortunate” with his art career.

The ease with which he created the famine scraperboard pieces for the BBC documentary surprised Rooney. Maybe it was the snowed-in Wicklow Mountain setting, a sense of isolation, a throwback to Black ‘47, but Rooney says he created those pieces almost in a dream.

“I had one hundred engravings to do for the BBC series 'The Story of Ireland' in three months, that’s one per day. I waded through the episodes of history.

"However, when it came to the Famine, something just clicked with me. They were real people. I was able to summon them from the past. I felt I knew who they were,” Rooney says, adding, “It’s like I am a reporter on TV, I’m here, the war is happening behind me, I’m sharing something that needs to be shared.”

Rooney's "Eviction Notice," one of 100 scraperboard artworks in the BBC series "The Story of Ireland."

The music, however, is a different story; Rooney is often filled with self-doubt. “Is it any good? Does it sound right?”

With the encouragement of co-producer on the project Declan O’Rourke, Rooney released his debut album of songs, "Bound Together," in 2015.

Following the help of Torsten Kinsella of the Irish post-rock group God is an Astronaut, Rooney created his musical soundscape, Echotal. This is the space where Rooney’s artistic and musical skills meet. Echotal means “a kind of sound valley.” Kinsella helped Rooney “feel the music, and connect it to the art like a soundtrack does in a film,” and their first digital EP, "Fire at Full Moon," was released in February 2023, including collaborations with London-based cellist Jo Quail, and the guidance of Kinsella as producer.

Anyone who has not seen Rooney’s illustrations set to Echotal’s music in “Famine” on YouTube will be hard-pressed not to get emotional while watching and listening.

Declan O’Rourke described Rooney’s Famine artwork best during his launch speech last year when the nine pieces found a permanent home in the Irish Workhouse Center in Portumna, Co Galway.

“Something extraordinary did happen when David executed the nine [Famine] scenes,” O’Rourke said. “All of his gifts and skills came together to forge what one can only call a mastery of his craft.”

Rooney has kindly expressed his support for Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum of Fairfield and is donating a limited edition print, Famine Ship, to future fundraising efforts.

Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum of Fairfield is the future custodian of the Great Hunger Collection —over 170 pieces of art and sculptures that tell the story of the Irish potato famine, one of the darkest periods in Irish history. Quinnipiac University picked the Fairfield location because of its vibrant Irish community and its perspective to display the art to a larger audience. The current IGHMF board meets twice monthly with Quinnipiac officials to ensure best practices are adhered to in transferring the collection to the new space in Fairfield.

Rooney’s website now has limited edition prints for sale, including a selection of the Famine Artworks. Click here to see more: Limited Editions | David Rooney

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments