This should have been the week when politicians of all stripes march out to the pitching mound, prove they never played baseball growing up, and people cheer just the same. But not this year, with coronavirus shutting down baseball.

So, Randy Roberts -- Purdue University professor, frequent visitor to Ireland, baseball fan -- has this suggestion.

“Read any number of great baseball books,” he told the Irish Voice. “It’s always been a game of the mind and the tongue. It’s a game that provides time to think and talk.”

Roberts own latest book is timely to an almost unsettling degree, from its nostalgic memories of baseball, to its tracking of a deadly disease that shut down cities and paralyzed the U.S.

Read more: The Irishman behind New York Yankee’s Babe Ruth

First, the baseball. Boston Mayor Andrew Peters “recognized the political opportunities of throwing out the ceremonial first pitch” at Fenway Park, writes Roberts in War Fever: Boston, Baseball, and America in the Shadow of the Great War (written with Johnny Smith).

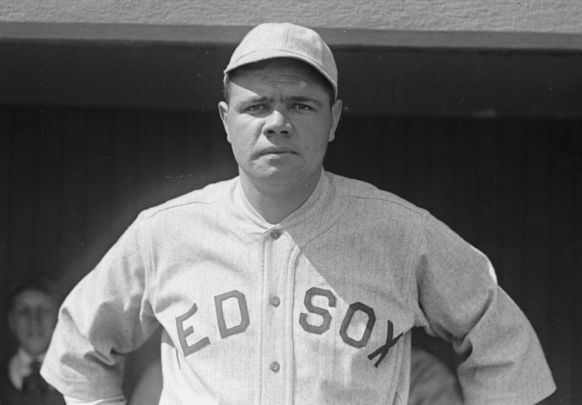

It was the start of what would become the magical season of 1918 for the Boston Red Sox, led by a fireballing pitcher who could also hit a bit -- Babe Ruth.

Mayor Peters emerged victorious following a bruising contest against James Michael Curley, whose “support of Irish nationalists and German-Americans” outraged Boston’s WASP establishment. Peters, Roberts writes, “promised to sweep the Irish out of office and clean up City Hall.”

“A vote for Peters,” opined one Irish Bostonian, “is a vote for the anti-Catholic, anti-Irish combination.”

As Roberts makes clear, this was a time of intense conflict -- ethnic, religious, political.

At the center of the rage was World War I. Americans had remained above the fray for years, but by late 1917, American “doughboys” were off to Europe, to assist the British, in their fight against the Kaiser.

That transformed cities like Boston into battlefields of their own, as War Fever notes. Irish and German immigrants had long been viewed with suspicion. Now, because many of them also held anti-war views, native-born Americans openly questioned their loyalty.

Roberts notes that one reason Boston’s star was known as “Babe” is because his birth name, George Herman, sounded so German.

In the summer of 1918, baseball temporarily brought Boston’s warring factions together. Babe Ruth and the Red Sox won what would turn out to be their only World Series of the 20th century. And they may not have even done that if the World Series were played -- as it is these days -- in October.

“Spanish influenza now has reached epidemic proportions in practically every state in the country,” The New York Times reported on October 16.

The Sox, however, had beaten the Chicago Cubs by early September.

By October, the pervasive virus had killed 3,500 Bostonians. And yet, as Roberts notes, ”on October 20, Boston officials announced that the worst had passed.” And so, “after being confined to their homes for three weeks…(Bostonians) flocked to the theaters and movie houses...celebrating the end of the closure order with suds and spirits.”

Another 1,300 Bostonians were killed by the pandemic.

Having researched Boston’s response to the Spanish flu, Roberts told the Irish Voice, “Don’t be quick to declare victory. Viruses are not games. Quick victories can translate into significant losses.”

Over the years, Roberts’ sports research has taken him to Ireland nearly two dozen times.

“I’ve done research on sports and Irish nationalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” he says. “I love the west coast, Dingle, Connemara, Donegal, but also Kilkenny, Armagh, Dublin, and Belfast.”

Indeed, Roberts has managed to balance business and pleasure.

“I’ve played most of the great golf courses in Ireland, as well as some off-the-beaten-track ones.”

When he will do so again -- when baseball will resume again -- is anybody’s guess.

Read more: Oral history archive celebrates 50 years of the Irish language in Boston

Comments