On January 15, 2009, US Airways Flight 1549, on a flight from New York City's LaGuardia Airport to North Carolina, struck a flock of wild geese moments after takeoff, losing all engine power.

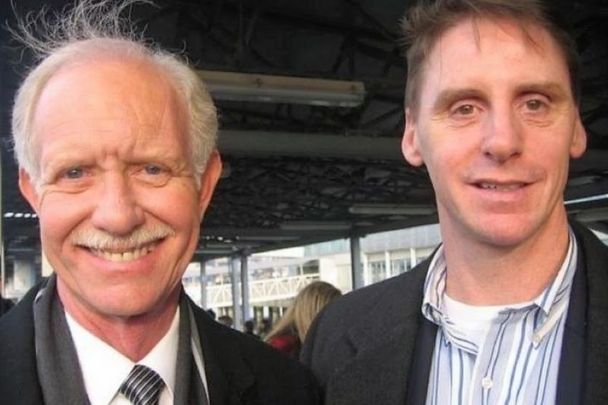

That landing of the suddenly powerless aircraft by Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, with miraculously no deaths, became known as the Miracle on the Hudson, the most successful plane ditching in aviation history. But what did it feel like for passengers who were there?

Irish American husband and father Steve O'Brien, now 57, whose policeman father hailed from Milton Malbay in Co Clare and whose mother came from Malin Head in Co Donegal, was on the flight in row C-15 that day.

A father and businessman (he works as a senior consultant in financial services), his mind was on the business ahead when he boarded what he thought would be an uneventful flight.

“We were supposed to take off from LaGuardia at 2:30 pm in the afternoon, but we ended up taking off at 3:20. It was a normal ascent until we reached about 3,200 feet and the plane collided with a huge flock of geese.”

You may be imagining a small impact, but you would be wrong O'Brien says. “It was a very violent hit. The plane actually shuddered in mid-air and then it just kind of stopped,” he told the Irish Voice, sister publication to IrishCentral, during a recent interview.

Then it started dropping. The cabin quickly filled up with a light haze, as if a lot of people had suddenly started smoking, but it had a very nasty electrical, burnt hair smell, and when it started everything became very quiet.

At this point, some people figured out the level of danger they were in and started screaming, he recalls.

“I remember Captain Sullenberger made a very sharp, almost like an unnatural left. He basically turned the plane into a glider. We just kept going lower and lower but nothing was being communicated to us. It was a very surreal experience, you know?”

Then he corrects himself. “But it is also the most real feeling I've ever had, you know?” he says. “Looking out the window I saw Pearl River. I grew up there so I knew where we were. I knew at that point we were not going to make it toward Newark, that we were kind of going south instead.”

O'Brien is 6'3 standing up, so he likes to sit on the aisle seat. Looking out the window to his right he could the George Washington Bridge. Then a voice near him said both of the engines were on fire.

“I had just got onto a plane and I thought holy hell, now I'm gonna die,” he thought.

In this same moment, the captain lined up the aircraft as they passed over the bridge. Then he finally picked up the microphone and said three words: "brace for impact.' They were crashing. It was really happening.

Sullenberger's plan was to land the plane on the Hudson River and hopefully survive the hit, then deal with the evacuation and rescue plan afterwards.

“We kept going and lower and lower,” O'Brien says. “I looked out the left window and I could see the West Side of Manhattan. A lot of people disconnect in a moment like this but I couldn't believe it was happening. I always say that it's like the opposite of a dream. You know, when you have a bad dream you can wake up. There was no waking up from this.”

When they hit the water, the plane bounced and bounced again. O'Brien could see water coming up to the window. Outside it was a bright sunny day.

The plane bounced again and the left engine tore off as it skidded. That's why the plane's nose is always facing Manhattan in all of the famous pictures, O'Brien explains.

“You could literally feel the nose go under the water then kind of pop back up again. Then there was just this feeling in the plane like we're in the water.”

He remembers some strangely beautiful sunlight coming into the plane. “I also remember that there was this kind of calm, peaceful feeling that something special had just happened. Everybody just kind of looked at themselves, sitting in the chairs, the seats, and it was like, we're all still here.”

Then all hell broke loose. In the back of the plane a hole opened up and water started coming in.

“I was seated in the middle of the plane, so I stood up to put my Blackberry – that's the phone I was using at the time – back in my pocket.”

The people behind him were already surging forward. Some were yelling, “Go, go, go.”

“I somehow ended up getting to the door of plane and there I saw that some people were in the water already. I said to myself, ‘Geez, that looks good compared to what was gonna happen five minutes ago,’ so I grabbed a floating seat cushion, stepped out onto the wing, and jumped in too.”

O'Brien's guiding thought – his only thought – was if he could get out of the plane before it sank he could see his kids again. The children were just eight and 10 years old when the plane crashed.

“When we were going down, I remember thinking about some kids I knew whose dads had died early. And that was hard. I thought, ‘God I can't believe this, I'm going to be like that. I can't believe I'm not gonna be here for my kids.’ It was immensely sad to think about.”

He pauses for a moment. “We all had a 10-year reunion a few years ago, the crash survivors, and I am still friendly with the woman I jumped into the water beside, as well as with some other people from the flight. I mean, it's a shared experience. There's only 150 people around that that's happened to.”

Does he still have post-traumatic stress from the crash, I ask?

“I went to counseling for it. You would notice yourself get angrier and things would set you off. I'd be in the car with my kids say and say, ‘Get out of the plane, come on.’ I'd use the word plane instead of car, you know, there were things like that, or I'd just get angry quicker.”

It wasn't pleasant but it subsided as the years went by, he confesses. O'Brien remembers going to his therapist and saying, “We were right there, we were all about to die. And then we somehow got yanked back up the cliff toward life.”

“My therapist told me there's an Irish term for what they call the thin places. Like, it could be the birth of a child or the death of a loved one, where there's a very thin veil between yourself and the other side – and God.”

“It does make you appreciate – and it takes time sometimes – but just the mundane things in your life. Like, I remember clearly, and I know this sounds ridiculous, but I remember thinking on the way down, ‘Who's gonna clean the garage at my house now?’ And then I just thought about the driveway, my own driveway, where I used to play basketball with the kids when they were little.”

It's not oh gosh I didn't do this big thing with my life, O'Brien explains. It's not I didn't climb this mountain or accomplish this or that. It's the little things that you're doing every day that you might even complain about that actually make up your life and they're all about to get yanked away.

O'Brien puts his bouncing back in the years that followed down to good old-fashioned Irish stoicism – and the unexpectedly happy ending. Everybody lived.

“I have good Irish resilience, right? We're resilient. You gotta be resilient. My parents always said don't complain. Somebody else always has it worse than you. So like I said, could I have done without it? Yeah, I definitely could have, but the experience is what it is and you have to make the best of it and take everything that comes with it, you know?”

*This column first appeared in the March 16 edition of the weekly Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral.

Comments