Poverty and lack of opportunity create social isolation, which leads to social alienation, and in the North, we have learned, or we should have learned, where that kind of dangerous alienation can lead.

Northern Ireland is in the midst of a suicide crisis. The problem is being compounded by overstretched mental health organizations finding themselves unable to cope with the demand for their services.

Another key factor is social conditioning. Many men still consider admitting to mental and emotional health issues a kind of weakness, something to be ashamed of that prevents them from seeking the help they need.

But studies show that social isolation is the last thing most people need in times of crisis, although for many their first instinct is to shut down and self-isolate. The North has also traditionally placed value on the 'hard man' image, and nothing seems to upend that image like a problem some men find they can't fix themselves.

Add to that the legacy of a bitterly divided society, where any kind of weakness can be seen as a problem, and you have a toxic stew that can make accessing services and finding help next to impossible.

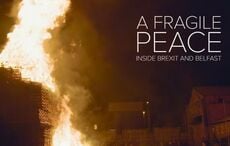

Another layer is the dysfunctional politics of the North itself. Where a society is in permanent conflict, where it has only achieved a tense truce, it cannot really develop and grow normally, and in consequence neither can many of the people who live there.

With its politics in a decades-long stalemate, this time due to the DUP's refusal to take its seats in the Assembly at Stormont, it can be hard not to despair of Northern Ireland or its prospects and even now after decades of violence and trauma not enough attention is being paid to the mental health toll the Troubles took on the general public in all communities.

After the Good Friday Agreement, we were promised a significant Peace Dividend, where the benefits of the peace would help to restart the long-dormant economy and bring needed inward investment and paying jobs to unemployment blackspots.

The investment came but it didn't lift all boats. In fact, the crisis has actually been compounded in working-class areas like the predominantly Republican Creggan estate in Derry and in predominantly loyalist Shankill Road, long-forgotten communities where social issues are only discussed after the latest sectarian attack.

We have failed to pay attention to the long legacy of violence, the social and often secret traumas that have never been discussed, we have seen that the violence itself canteen be overlooked or avoided by government campaigns to move beyond the Troubles.

But what kind of message are we sending to our future selves and the future of the North if we won't or can't address our own past and what it has made of us?

I have often been struck by the sheer foolishness of overlooking the very communities that first challenged and reacted to Northern Ireland's once insanely unequal societies.

Forgetting the people that ignited the conflict, letting their communities falter and sink, seems to me to forget the hard lessons we learned during the conflict and could be setting the stage for a host of new troubles.

Stalemate is the top note of the current situation in the north and its reflecting a massive but not so hidden emotional and mental health crisis in the wider society.

Ignoring or underfunding the social services needed to tackle the post-traumatic stress of the legacy of conflict should have been one of the first factors baked into the original peace dividend, not an afterthought.

Poverty and a lack of opportunity create social isolation, which in turn leads to social alienation, and in the North, we have learned, or we should have learned, where that kind of social alienation can lead.

It's pointless to sit and wait for political parties who have already tacitly admitted they have no interest in making the politics of the region work. They have neither a plan for nor an inclination to make positive change. Instead, the British and Irish governments will have to step in to do the work that some of the elected parties seem incapable of.

Suicide happens to people of all ages, all walks of life, all points of view. There is help out there, but often not enough, or not alert to the particular needs and outlooks of the society it tries to serve.

It's time the two governments drafted a Marshall Plan to address the lack of opportunity, services, employment, and the massive social isolation and mental health issues they left off the page back in 1998.

Comments