On the eve of the Civil War, New York City was home to over 200,000 native born Irish, one in four of the total population then. Tens of thousands of them later went to war – a fact that still has yet to be fully appreciated in Ireland. In "The Forgotten Irish: Irish Emigrant Experiences in America," author Damian Shiels reminds us why we have only grasped half the story.

Growing up in Ireland, we barely hear a word about the Irish who had fought in the American Civil War. Instead we hear almost exclusively about our own conflicts.

We hear all about the Great Hunger too: the causes, the effects, the enforced emigration that followed as the destitute Irish took to their coffin ships to escape the disaster.

What happened to the Irish once they made landfall in the United States was, we seem to have decided with our odd insularity, entirely their own business.

Like Oisin when he rode off to Tir na nOg, out of sight was out of mind. Good luck to him. There were disasters enough to be going on with back home.

This lack of curiosity was partly geographic; America was an ocean away. But it was also psychological. It hurt to contemplate the physical severances that were unlikely to be mended.

In the 19th century the Irish actually waked intending immigrants as though they had died, because after they set off they effectively had.

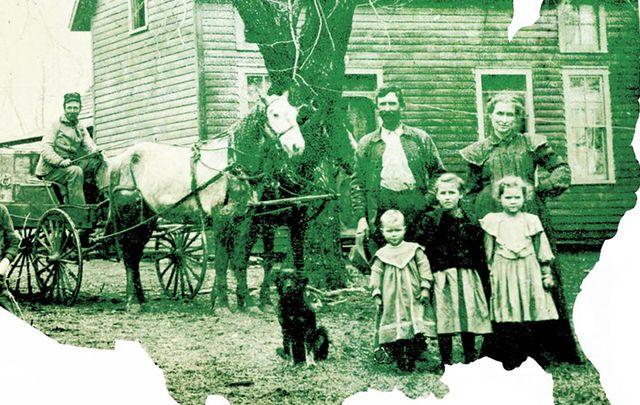

Immigrants arriving to Ellis Island, in New York.

So it falls to our historians to unite the story of the Irish. Uniting Ireland was never simply about borders or sovereignty it turns out. It is also about reuniting our broken story.

In "The Forgotten Irish," historian Damian Shiels conjures the 19th century experiences of the Irish in America with the skill of a dramatist. Assembling letters that let the long dead speak in their own words, he bridges a divide between their time and our own that does more than simply recite their history – it reconnects us to them.

In that regard we are living in a golden age. Reclaiming our lost or abandoned heritage and history has been the work of Irish artists and academics for almost 100 years, but the last three decades have been a particularly productive era.

Around 1.6 million native-born Irish people were living in the United States on the eve of the Civil War. That staggeringly large number was explained by British oppression and the Great Hunger. Exiles in their own country, they immigrated to the great industrial cities of America's north because they had no choice.

Once they made landfall they were someone else’s problem – not the Anglo Irish landlords who fleeced them, or the laws that exploited them so that they had no choice but to flee.

The journeys they made in that century are no longer possible. That’s because when they left they were taking their language, their few possessions and their entire futures with them; they were as lost to their mother country as if they were journeying to the moon.

By delving into the widows and dependent pension records of the Irish women who were widowed by the American Civil War, Sheils has opened a window into the intimate details of their lives, offering us private snapshots of their lives and experiences in Ireland and America. It makes for eye-opening reading.

The Irish brigade fighting in the American Civil War.

Sheils has a writer’s eye for the telling detail. Perusing the Civil War files in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., he examined the records of soldiers, their families and loved ones, tens of thousands of which happen to have been Irish-born.

As well as telling the stories of their involvement in the Civil War, these records follow their lives across decades, from their journey from Ireland to their new lives in America. Even the illiterate are given a hearing, since their hearers transcribe their experiences.

Just think of what so many of them went through. First there was the crisis of the Great Hunger and the voyage to America. Then the Civil War began, representing another great trauma in their lives.

By the time the war concluded, Sheils writes, some 200,000 Irish men had participated, the vast majority of them – as many as 180,000 – wearing Union blue.

There is no official record of how many native born Irish died in the Civil War, but it inarguably ran into the tens of thousands. Left behind were their widows, children and parents who would later seek pensions based on their service, in the process recording and leaving a record for us of how they had lived and died.

Despite the scale of the Irish involvement in the Civil War, the number of pension recipients in Ireland was small, a reminder of how rare it was for Irish emigrants to return to their home country in the 19th century.

From a list of thousands, Sheils’ book examines the lives and personal stories of just 35 Irish families, but in the process he tells the story of the Irish in that transformative and tumultuous century.

What unites these stories – the reason we have them – is loss. Each letter is written by the widows and dependents that were left behind.

There was, of course, much more to the full picture of the Irish in America, including much more happiness and success, but these are the stories of the bereaved, and the details that slip out of these letters makes them treasure stores of experience.

One elderly couple in Donegal is a particularly poignant example. In 1869 (corrected – Ed.) the Coyle family received an eviction letter from the Third Earl of Leitrim, William Sydney, a notorious landlord despised throughout Ireland.

Read more: Donegal in Pennsylvania - chain emigration and the American Civil War pension files

In their mid-seventies and infirm, the eviction could have left them destitute but for the service of their deceased son, who had died from mistreatment in captivity at the hands of the Confederate Army five years earlier. The Coyles’ application for a United States pension was successful, although it is not known if it was sufficient to save them from life on the road.

We do know what happened to the Third Earl of Leitrim, however. A decade after he sent the letter to the Donegal couple, a group of local Fanad men lay in wait for him along a road, killing him, his driver, and his clerk as they passed. To this day the men who killed him were never named or captured, but a monument was later erected to the “Fanad patriots” who sealed his fate.

By offering up the tales of these 35 families, it is possible to discern a fuller portrait of the century and the pictures that emerge are often immensely moving.

The great work ahead of our scholars and artists in this century will be to reunite our broken narrative. Sheils is alive to the implications of that undertaking, remarking that although the Irish experience of the Civil War is now well known and well recorded in the United States, it’s still largely a mystery in Ireland, where the sheer scale of the Irish involvement has yet to be fully appreciated. It’s time.

The Forgotten Irish: Irish Emigrant Experiences In America, The History Press $26.95

Comments