This week marks 100 years since the Government of Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain divided Ireland into two self-governing polities.

Stephen O’Neill’s Irish Culture and Partition 1920-1955 is forthcoming with Liverpool University Press. From 2019-2020 he was the National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow with the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Here he examines the culture and the centenary of the partition

Between Brexit and the calls for a border poll, the partition of Ireland has come under increasing scrutiny in the past five years. The renewed interest in how Ireland came to be divided in the middle of its revolutionary period has emerged alongside debates about the future of the island. As unionists and the British Government organize parties for the one-hundredth anniversary of ‘Northern Ireland’, questions remain over how many more years it might be there to celebrate. These questions have been cast into sharp relief by historians marking the centenary of the state in newspaper series, academic conferences, documentaries, and even discussion shows on RTÉ and the BBC. In short, the partition of Ireland is a hot topic right now.

This newfound interest in the division of Ireland is not before time. Since the 1920s, the process of establishing the Irish border has often been overshadowed by other major events of the period such as the War of Independence (1919-1921) and the Civil War (1922-23). In 1951 the journalist and historian Dennis Gwynn claimed of partition that ‘the complete story has never been published… there has been no coherent narrative even of the facts which are already available’. As Gwynn’s comments suggest, this lack of a story owes much to the chaos, secrecy, and confusion in which partition began, and even more to a general unwillingness to study how it came about afterwards. A century on from the implementation of partition, and seventy years after Gwynn’s lamentations, the full story of partition is yet to be told. As if to underline this fact, historians have only just settled upon a date for the ‘birth’ of the northern state, and the recent calls to open up the archives of the Ulster Special Constabulary have demonstrated how some facts are withheld even today.

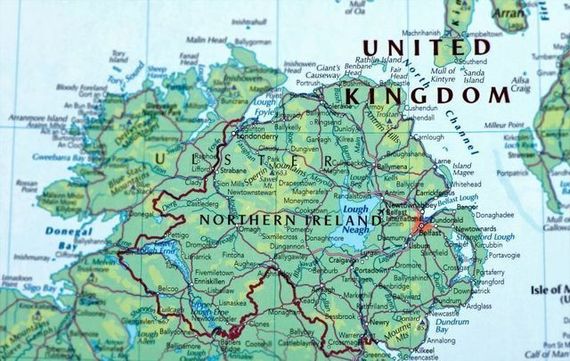

Map of Northern Ireland

The absence of an agreed story of Ireland’s division has had a significant impact on the culture of Ireland since 1920. This impact was most powerfully demonstrated in December 2020 when Tai Shan Schierenberg’s portrait of Seamus Heaney was adopted as an emblem for the blandly optimistic ‘Our Story in the Making: NI Beyond 100’ branding by the Northern Ireland Office. Its inclusion provoked anger about the tame narrative of partition that the British Government sought to promote, with little reference to the ways in which northern Catholics like Heaney had been treated by the northern state in the past century. As the Irish Times journalist Freya McClements summarized, the episode demonstrated a ‘great ability to create misery where there might otherwise be harmony’ when it came to the north of Ireland. But when Heaney was recently also described by a British race relations report as a writer ‘steeped in British cultural traditions’, some of the anxieties around his place in the divided cultural traditions of these islands seemed to be justified.

The difficulty of creating harmony on the island has also been caused by the ways in which cultural and social identities were enshrined by the act that divided Ireland in 1920, and the ways in which the ‘southern’ and ‘northern’ states have articulated new-fangled identities ever since. Partition was based on a British reading of the island as ‘tragically divided’ between two incompatible religious and political identities, and culture played an important role in promoting visions of ‘Ireland’ and ‘Ulster’ which simplified the complications of the 1920s. One way of explaining how these limited representations of Irish identity have lasted for so long is to return to the culture of the 1920s, and begin to understand how terms like ‘Ireland’, ‘Northern Ireland’, and ‘Ulster’ – which was reimagined as a six-county rather than a nine-county province – became so divided as to be almost opposites.

But in returning to this period we can also begin to see alternative ways of seeing Ireland which – however idealistic – undercut these exclusive visions. As the writer and TD Piaras Beaslaí said during the Treaty Debates of 1921 and 1922:

Ireland is the Irish people…. the old women by the fireside, the young men working in the fields and the girls in the shops, the Orange working-man of Sandy Row and the Molly Maguire of South Armagh, the men on city tram cars, all types and classes, good, bad or indifferent… Remember those people are Ireland. Ireland is not a formula but a fact.

As well as a chance to understand how the border came about, the centenary is a timely opportunity to trace how visions like Beaslaí’s were forsaken for the divisive and exclusive identities that were quickly adopted by both states on the island from the 1920s. Recovering these visions will allow us to understand the continuing importance of culture in Irish politics and society.

Trinity Long Room Hub Arts & Humanities Research Institute are hosting two online events with an array of excellent speakers on Friday, May 7, 2021. This special centenary joint symposium between Trinity College, Dublin and the Queen's University, Belfast will address the cultural, political and social legacies of the Irish partition in 1921.