The two people in the 20th century most connected with Dublin are James Joyce and Michael Collins. Joyce, through his books, brought the second city in the British Empire to life with his poignant stories about the city and its inhabitants. He knew the city inside and out and was a native.

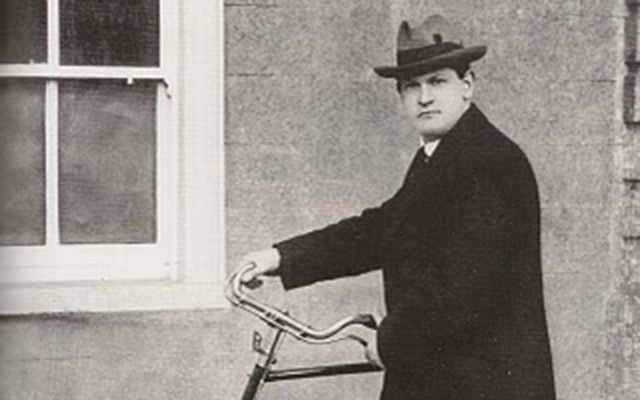

Collins, on the other hand, was a West Cork farm boy who spent ten years in London working in the British postal system. He moved to Dublin in late 1915 to get ready for the 1916 Easter Rising. After spending eight months in prison after the Rising he returned to Dublin where he would roam the streets freely and unmolested even though the British—courtesy of Winston Churchill—had placed a £10,000 bounty on his head.

How did Collins survive in Dublin? It’s simple. He was protected by Dubliners. He had no home, slept in a different bed every night, yet the British still could not catch him. It is often said that rebels in Collins’ situation were “on the run.” In Collins’ case, “on the run” meant business-as-usual.

The Munster, Vaughan’s and the Wicklow

Collins, being in the situation he was, had an affinity for hotels. Three of his favorites were the Munster at #44 Mountjoy Street, Vaughan’s not far away at #29 Parnell Square, and the Wicklow, at #4 Wicklow Street. What is amazing, is that all three buildings are still standing today, although no longer hotels.

The Munster Hotel was on a cul-de-sac under the shadow of the forbidding Black Church. It was a favorite of Irish revolutionaries. On the night before the Rising Seán MacDiarmada is said to have stayed here. It was also right across the street from #30, the home of Dilly Dicker, a one-time girlfriend of Collins and one of his trusted agents. By 1919 the British knew that the Munster was one of Collins’ haunts and he was forced to abandon it. Strangely enough, he still brought his laundry there and often picked it up himself.

Read more: Greatest quotes of Irish hero Michael Collins recalled

The the home of Dilly Dicker, a one-time girlfriend of Collins and one of his trusted agents. Image: Dermot McEvoy.

A few blocks away was Vaughan’s Hotel, his fabled “Joint Number One,” at the top of Parnell Square, overlooking what is today the Garden of Remembrance. It was a regular meeting place for Collins and his men and also a favorite for British touts looking to find Collins. It was at Vaughan’s the night before Bloody Sunday 1920 that Shankers Ryan, tout supreme, would trail Dick McKee, commandant of the Dublin brigades, and Peadar Clancy, McKee’s vice-commandant, back to their bunks in Nighttown and report them to the British. Arrested, they would be beaten to death the following day in Dublin Castle “trying to escape.” Two months later Collins’ Squad would track Ryan down and shoot him dead as he bellied up to the bar for his morning eye-opener.

Christy Harte, the mute guardian angel

The location of Vaughan's Hotel. Image: Dermot McEvoy.

Amazingly, Collins used Vaughan’s right up through the Truce. How did he get away with it? Well, he had a guardian angel by the name of Christopher (Christy) Harte, the night porter, who knew all and said nothing.

I recently stumbled across Christy’s witness statement at the Bureau of Military History. I was surprised that Christy had made a statement. I was even more surprised that the statement was but one page long. And Christy did not write it himself; his story was told to the Bureau of Military History and is thus transcribed in the third person. At the time Christy was working as a waiter in the officer’s mess at McKee Barracks. It appears that this job might have been an award from the National Army for his years of loyal service to Collins. Ironically, if he was working the night before Bloody Sunday he might have been one of the last people to see Dick McKee alive as he left Vaughan’s for the night. In the statement, dated 15 Eanáir [January], 1947, Harte tells his amazing story:

“He [Harte] was arrested shortly before midnight on the night of 31st December, 1920, and detained in Dublin Castle where he was ill-treated. The time was fixed in his memory by the fact that church bells were ringing in the ‘New Year’ as he was entering Dublin Castle under arrest. A few days later, the exact date he cannot remember, while still in custody in the Castle he was questioned in a dark room as to his knowledge of Collins. He denied all knowledge of him, but was confronted with the statement that he had frequently been seen carrying Michael Collins’ bicycle down the steps of Vaughan's Hotel from the hall into the street.

Read more: Michael Collins signs the Treaty and his death warrant 95 years ago today

“It was suggested to him by his unseen questioner that he was a poor man and that he would like to earn some money. He was informed that the authorities would be prepared to pay a large sum, perhaps up to even £10,000 for information leading to the capture of Collins.

“The scheme suggested to him was that on some occasion when Collins would be in Vaughan's Hotel, he, Christopher Harte, should ring up the Castle, Extension 28, and give the following message:

“Brennan: The portmanteau is now ready.

“The text was handed to Harte on a slip of paper. He was instructed to memorise it carefully and then destroy it. Needless to say, Harte did at any time, do as suggested.”

The statement goes on to say that Christy gave the note to a “Dr. Ahearne,” an officer in the National Army. I searched Tim Pat Coogan’s biography of Collins and came up with a Dr. Leo Aherne, who tended to Collins’ body after he was killed. It is probable, although the spelling is different, that this is the one and the same Aherne. The curiosity, of course, is why did Aherne want the note? Perhaps Collins was planning a trap for Dublin Castle?

Dermot McEvoy outside Vaughan's hotel. Image: Dermot McEvoy.

The late Willie Doran—the anti-Christy Harte

Of course, for every Dublin hero like Christy Harte there was always a British tout willing to turn Collins into a personal bounty. One such person was Willie Doran, the porter at the Wicklow Hotel at #4 Wicklow Street, which is just off Grafton Street and right next to Weir Jewelers, which has been at the same location for more than a century. In fact, Collins brought his engagement gift, a watch, for his fiancée Kitty Kiernan at Weir’s.

A member of Collins’ Twelve Apostles, Joe Dolan, tells what happened to British spies as soon as Collins found out:

“We used to go round to maids and, boots in the different hotels and get information from them,” Dolan wrote in his witness statement.

“Collins got information from Paddy O’Shea that Doran was giving information to the British. Collins used to dine in the Wicklow Hotel regularly and was satisfied that Doran was a British agent. There was a delay in executing this spy, we had been trying to get him for a fortnight, and [Liam] Tobin [Deputy Director of Intelligence] turned to me one day and asked me would I carry out the execution. I said I would if I got Dan McDonnell to go along with me, so the two of us were detailed to carry out the job. Dan McDonnell already knew Doran, and the two of us walked to the door of the hotel and asked for Paddy O’Shea. Just then Doran came out of one of the rooms, I think it was the dining room, and Dan McDonnell said, ‘That’s Doran.’ I produced my revolver and shot him through the head and the heart, and. McDonnell shot him through the stomach. We had a covering party and we had no difficulty in getting away.”

What is interesting about this story is that there is an ironic twist. Doran’s widow, destitute with children, thought her husband was killed by the British and came to Collins, looking for money. Collins gave her money out of Sinn Féin funds, saying, “The poor little devils need the money.”

This tale of two porters shows the loyalty of the Dublin people, their devotion Collins, the ruthlessness of Collins, but also shows Collins was a man with a heart. And he was also lucky that he had another Harte, Christy, in his corner.

Dermot McEvoy is the author of the "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising" and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village", both now available in paperback, Kindle and Audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached [email protected]. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/13thApostleMcEvoy/

Comments