It was led by Sir Cahir O'Doherty, the Gaelic lord of Inishowen, the rebellion was both a personal vendetta and a reflection of broader tensions between the English authorities and the Gaelic Irish nobility following the Nine Years' War (1593–1603).

Although short-lived, the rebellion marked a significant chapter in the decline of the traditional Gaelic order and the tightening grip of English rule in Ireland.

Background: From Loyalist to Rebel

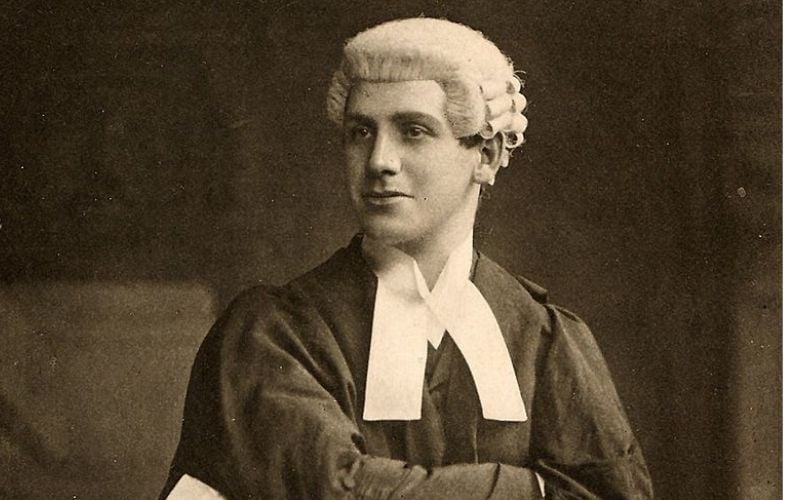

Sir Cahir O'Doherty, the young lord of Inishowen in County Donegal, initially supported the English Crown during the Nine Years' War, joining forces with Governor Sir Henry Docwra in 1600 at just fifteen. The Crown was fighting against a powerful Gaelic alliance led by Hugh O'Neill, the Earl of Tyrone, and Hugh Roe O'Donnell, the Earl of Tyrconnell. O'Doherty's support earned him praise and a knighthood, thanks to Docwra's recommendation.

Following the war, peace was brokered by the Treaty of Mellifont in 1603. Despite submitting to King James I, O'Neill and O'Donnell were still viewed with suspicion by English authorities. In 1607, the two earls fled Ireland in what became known as the Flight of the Earls, leaving a power vacuum in Ulster, which O’Doherty sought to fill.

However, O'Doherty's fortunes changed with the appointment of Sir George Paulet as the new governor of Derry. Paulet encouraged by King James of England took a hardline approach toward Gaelic lords, including loyalists like O'Doherty. Docwra, disillusioned with the government's broken promises of land grants to Irish allies, resigned. Although O'Doherty retained most of his lands, he lost Inch Island, a blow to his ambitions.

The Canmoyre Woods Incident and Rising Tensions

The atmosphere in Ulster remained tense. In this climate, Paulet became suspicious of any Gaelic gatherings. When O'Doherty and his followers were spotted near Canmoyre Woods in what was a wood-cutting expedition, Paulet assumed it was a rebellion in the making and marched out with troops. O'Doherty, angered by this assumption, travelled to Dublin to clear his name with the Lord Deputy Sir Arthur Chichester. However, his visit coincided with the escape of another noble, Lord Delvin, making O'Doherty appear guilty by association.

Rather than exonerate him, Chichester demanded a hefty bond of over £1,000 and forbade O'Doherty from leaving Ireland to petition the king directly. No solid evidence linked him to any conspiracy, but the government's treatment was pushing O'Doherty toward rebellion.

Read more

A Tipping Point: Personal Insults and Political Isolation

Despite the mistreatment, O'Doherty remained loyal to the Crown. He sat on the jury that attainted the Earl of Tyrconnell for treason in early 1608 and cultivated connections at court, seeking a position in the household of Henry, Prince of Wales. But Paulet's personal insult, striking O'Doherty in the face during a visit to Derry, was the final straw.

Spurred by humiliation and feeling betrayed, O'Doherty began plotting an uprising. He was reportedly encouraged by Sir Niall Garve O'Donnell, a neighbour with possible ambitions of seizing O'Doherty's lands. Still reluctant, O'Doherty even handed over his own relative, the fugitive Phelim MacDavitt, to prove his loyalty. Ironically, MacDavitt was released just in time to join the rebellion.

O'Doherty famously remarked that he would now "play the enemy" since the authorities would not accept him as a friend. On the eve of the uprising, he dined with his friend Captain Henry Hart, constable of Culmore Fort. O'Doherty unsuccessfully pleaded with Hart to surrender the fort. Ultimately, it was Hart's wife who tricked the garrison into an ambush, allowing O'Doherty to seize the fort and its weapons.

In a cruel twist of fate Unbeknownst to O'Doherty, orders had been sent from London the same day approving his requests, including the return of Inch Island but his rebellion had begun!

The Rebellion Erupts: The Burning of Derry

On April 19, 1608, armed with weapons from Culmore, O'Doherty led approximately 100 men in a surprise attack on Derry. The assault began at 2:00 AM. The lower fort fell without a fight, while the upper fort offered more resistance but was eventually overwhelmed.

The insurgents targeted officials they blamed for their grievances. Governor Paulet was killed by MacDavitt, as was Sheriff Hamilton. O'Doherty declared he did not intend to spill blood unnecessarily, releasing many prisoners while holding some key hostages. He then ordered the town of Derry burned, including homes and public buildings, reducing it to ashes.

The Rebellion Spreads

The successful capture and destruction of Derry temporarily boosted rebel morale. O'Doherty's forces, which grew to around 1,000 men, took control of Doe Castle and threatened Coleraine. The Scottish settlers of Strabane fled in panic. The town of Kinard was attacked, and its Crown-allied leader, Sir Henry Og O'Neill, and his son were killed.

While avoiding lands belonging to the exiled Earl of Tyrone, O'Doherty's supporters tried to frame their cause as part of a broader Catholic resistance. Some hoped the Earl of Tyrone would return with Spanish aid to lead a larger movement against Protestant English rule. O'Doherty declared that his actions were motivated by "zeal for the Catholic cause."

Still, it remained possible that the Crown might offer concessions to end the conflict peacefully. This strategy had worked in previous rebellions. However, with memories of the Nine Years' War fresh and suspicions high, the English response was swift and forceful.

Read more

The Tide Turns: Chichester's Counteroffensive

Lord Deputy Chichester, initially blamed for mishandling O'Doherty, responded decisively. He rallied available troops and local militias, dispatching a 700-strong force under Sir Richard Wingfield. These troops were ordered to conduct a "thick and short" campaign to crush the rebellion quickly.

Wingfield's army overran Inishowen, capturing Buncrana and recovering the ruins of Derry. They seized Burt Castle, capturing O'Doherty's wife and son and freeing English prisoners. These losses undermined rebel morale. O'Doherty's supporters pressured him into engaging Wingfield directly.

The Battle of Kilmacrennan: The Final Stand

On July 5th 1608, Sir Cahir O'Doherty led his remaining forces to meet Wingfield near Kilmacrennan in County Donegal. O'Doherty chose the battlefield carefully, favouring terrain unsuitable for cavalry. Despite this, the battle was short lasting less than an hour.

O'Doherty was fatally shot in the head during the skirmish. His death caused the immediate collapse of the rebel army. English troops pursued and dispersed the remaining fighters. O'Doherty's head was severed, displayed in Dublin, and earned a £500 reward for the soldier who took it.

With their leader gone, many rebels surrendered or were captured. Phelim MacDavitt, wounded and caught in woodland, was executed and his head displayed alongside O'Doherty's. Civil courts in Lifford tried and executed other captured rebels. Chichester's rapid suppression of the rebellion was praised in London.

Final Resistance: The Siege of Tory Island

Although most resistance collapsed after Kilmacrennan, one group led by Shane MacManus O'Donnell retreated to Tory Island off the Donegal coast. They fortified a castle but were soon besieged by Sir Henry Folliott from Ballyshannon.

In a desperate bid for pardon under "Pelham's Pardon," which required turning on one's comrades, the castle's commander, Sir Mulmory McSweeney, began killing fellow defenders to present their heads as proof of loyalty. He was killed by his own men, who then turned on each other. Those who survived the internal bloodshed were pardoned.

Historian Pádraig Lenihan described this grim finale as "a fitting epilogue to the disunity and duplicity of Gaelic Ireland."

Legacy of the Rebellion

O'Doherty's Rebellion, though brief, had lasting consequences. It extinguished the last flicker of organized Gaelic resistance in Ulster and provided the English Crown with justification to accelerate the Plantation of Ulster. The burning of Derry and the subsequent devastation reshaped the region, paving the way for a new political and cultural order dominated by Protestant English and Scottish settlers.

Sir Cahir O'Doherty's transformation from Crown loyalist to rebel leader exemplifies the complexities of Irish English relations during this period. His rebellion was not only a personal act of defiance but also a symptom of a larger, systemic alienation of the Gaelic nobility.

In the end, O'Doherty's revolt stands as a tragic but telling episode in the collapse of the old Gaelic world and the rise of a new colonial order in Ireland.

Read more

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments