Aviators John Alcock and Arthur Whitten-Brown were the first people in history to fly across the Atlantic Ocean on June 15, 1919.

Two of the unsung heroes of global aviation are being celebrated in a small Co. Galway town this week as the people of Clifden remember the men who created history when they crash-landed in a Connemara bog exactly 100 years ago.

British aviation heroes Sir John Alcock and Sir Arthur Whitten-Brown startled the locals when they landed in the bog at about 8.30 am on Sunday, June 15, 1919, becoming the first men in history to fly across the Atlantic Ocean.

The men’s brave, some would say reckless, feat changed the face of aviation, generated headlines all across the globe, and saw them collect a handsome £10,000 reward in London a few days later.

Alcock and Brown had endured an extremely uncomfortable and difficult journey over the previous 16 hours. They were hugely relieved to see two islands off the west coast of Ireland before skilfully landing their aircraft beside the Marconi Wireless transmission station, about 7km outside Clifden.

Galway-based historian Tom Kenny, whose grandfather Tom ‘Cork’ Kenny was the first journalist on the scene, recalled this week that the men had endured a harrowing and uncertain journey after leaving St John’s in Newfoundland.

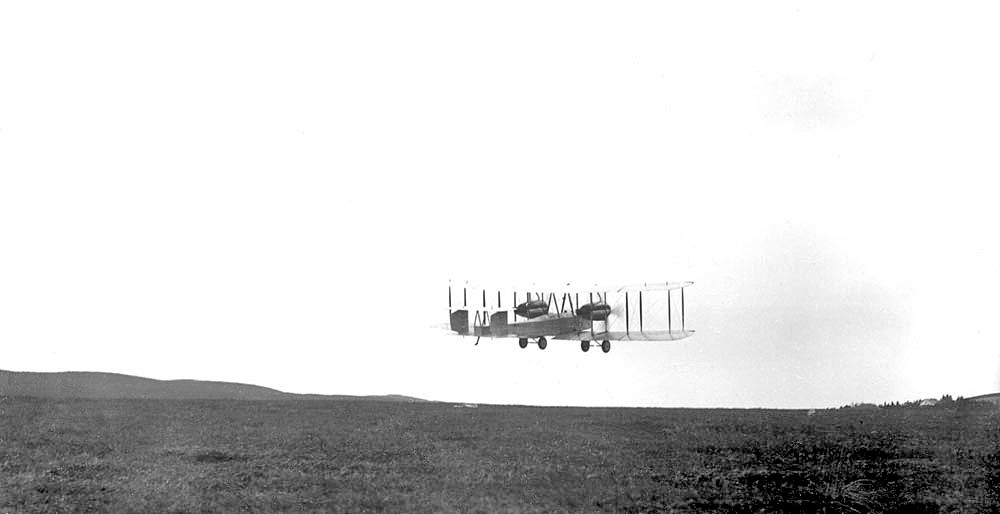

Vickers Vimy aircraft of Captain John Alcock and Lieut. A.W. Brown ready for trans-Atlantic flight, Lester's Field, 14 June 1919, St. John's, Newfoundland. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

They were chasing the £10,000 reward which had been offered by the owner of the London newspaper, the Daily Mail, to the first person to cross the Atlantic in an airplane. It was the equivalent of well over $1 million in today’s money.

“The journey was very difficult. They had some sort of a heating system built into their clothing, and that went. They had a radio, and that went. They could hear other people talking, but they couldn’t radio out to anybody,” said Mr. Kenny, of Kenny’s Bookshop in Galway, this week.

“They ran into sleet and snow, a lot of cloud and fog, and the journey was extremely bumpy. They were in an open-air cockpit. Holding onto the controls, which Alcock was doing, was described to me by an airline pilot as like trying to lift a bag of flour for 16 hours. It was that heavy. Equally, Brown had a very difficult time. They had no way of judging where they were. They only saw the stars once or twice very briefly through the clouds.”

It took them 15 hours and 57 minutes to cross the Atlantic.

Alcock and Brown takeoff. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Most of the good people of Clifden were either in bed or at Church when the plane began to circle over the town, although a seven-year-old boy, who had missed Mass because of illness; a farm laborer out in the fields; and an Australian soldier on his honeymoon were among those to see the first plane reach Ireland from North America.

The men had no navigational aids and twice saw their plane go into a spiral. After circling the town of Clifden, they decided to land near the radio station – mindful of the need to tell the world that they had managed to achieve their goal and to make sure they would receive their prize.

Viscount Northcliffe, the owner of the Daily Mail, had announced the £10,000 prize to the first person or persons who could fly non-stop across the ocean in 1913. It was deemed to be an impossible task at the time and competition to win the huge prize was suspended throughout the First World War.

When the British newspaper announced that the prize was up for grabs again after the Armistice was signed in November 1918, a race began. Four teams assembled in Newfoundland, the nearest land in North America to the continent of Europe.

A month before Alcock and Brown’s successful flight, a rival crew had flown for 14 hours only for their engine to die. Harry Hawker and Kenneth Mackenzie Grieve managed to land their plane on a shipping lane, where a Danish steamship carried them to safety.

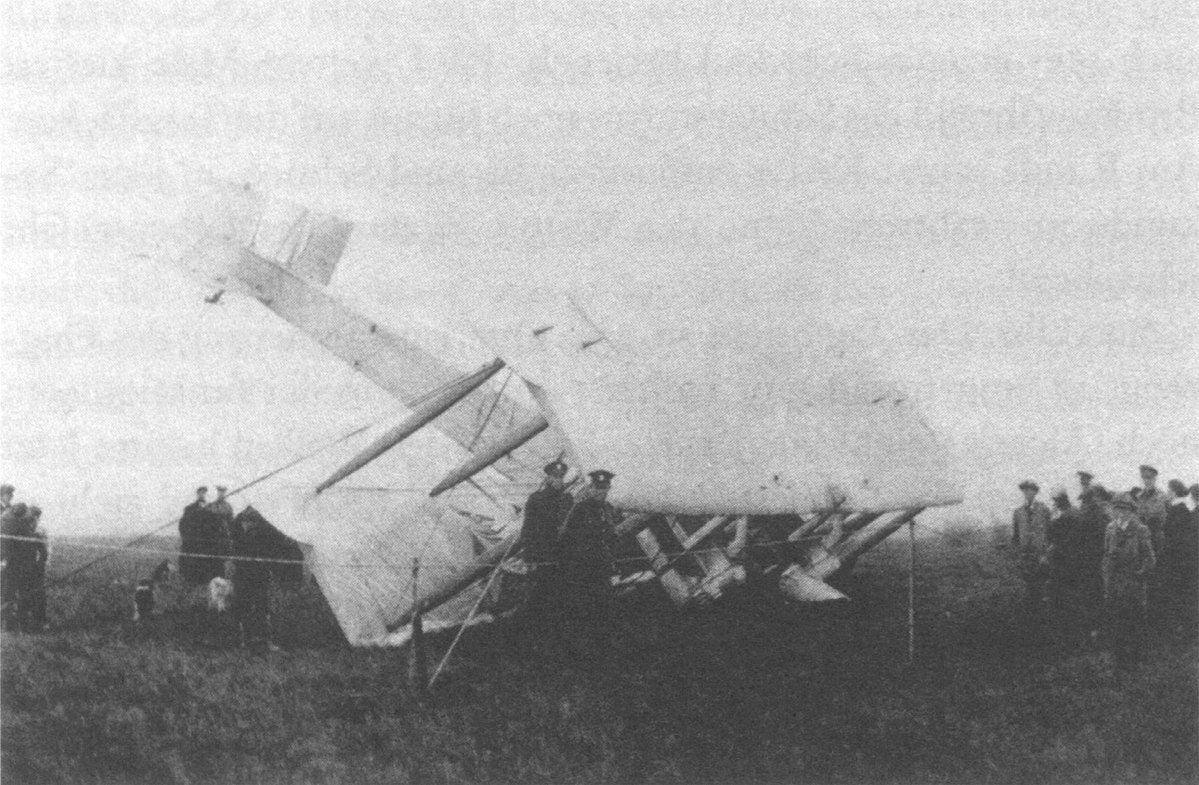

Alcock and Brown had never intended to land in Clifden on that June morning in 1919. They had aimed to get to London or Dublin, but necessity forced them to land in the West of Ireland. As soon as they landed, the nose of the plane began to sink into the bog.

The landing site. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A policeman in Clifden tipped off Tom ‘Cork’ Kenny, then editor of the Connacht Tribune newspaper in Galway, about the unusual arrival. Kenny raced to his Model T Ford car and made the 50-mile journey to Clifden, where he was delighted to get an exclusive interview.

The newspaper man’s grandson recalled that Brown was extremely shy, but Alcock enjoyed having fun with the local people and gave Kenny an exclusive interview. He said that they were “jolly pleased” when they saw land in Ireland after their grueling 16-hour journey.

“In those days, if you crashed your plane you didn’t walk away. They were composed and they pre-planned the landing. They thought it was a meadow, not a bog. They landed with a small bump. Eventually, the nose dipped down and the plane went over a bit on its side,” said Kenny.

Kenny’s grandfather brought the two men to Galway, where there was a superior radio system to the one in Clifden. The business community of the city held a reception in their honor. From Galway, Kenny was able to radio the story of the historic first transatlantic flight to newspapers all over the world.

“Sleet fell and our radiator shutters got frozen up,” said Alcock, in Kenny’s report for The Irish Times. “All our petrol gauges were covered over with ice. The weather was very rough and very bumpy and the wind was blowing hard right down to the water.”

As reporters from all over the world flocked to Galway, Tom ‘Cork’ Kenny brought them in the opposite direction. The three men boarded a train to Dublin and then hit for London, where Winston Churchill presented Alcock and Brown with the £10,000 prize before awarding them with knighthoods of the British Empire.

“By all accounts, Tom ‘Cork’ enjoyed the experience. He traveled with Alcock and Brown to Dun Laoghaire. All these journalists rushed past them on their way to Clifden. They didn’t recognize the two boys!”

Given that Alcock and Brown’s flight changed the face of aviation forever, it is perhaps surprising that their story is not better known by people all across the world.

Memorial to Alcock and Brown at the landing site in Derrygimlagh, Clifden. Photo: Dermot O/Flickr

Kenny believes the men never achieved the fame their exploits deserved because Alcock was killed in an accident on his way to the Paris Air Show in December 1919.

Brown, who was by far the shyer of the two men, never really recovered from the death of his companion. He was far more reluctant to seek the limelight and the story of how they crossed the Atlantic was almost forgotten following his death in 1948.

“The story hasn’t got the credit it deserves over the years,” said the younger Kenny. “My grandfather’s interview with Alcock was the equivalent of getting an exclusive with Niel Armstrong just after he had landed on the moon. It’s a great story.

“Thankfully, Clifden has been remembering them with a fantastic series of events and talks to mark the centenary this week and people across the world are starting to re-discover the story of these brave, unsung heroes.”

--

*Ciaran Tierney won the Irish Current Affairs and Politics Blog of the Year award at the Tramline, Dublin, in October 2018. Find him on Facebook or Twitter here. Visit his website here - CiaranTierney.com. A former newspaper journalist, he is seeking new opportunities in a digital world.

* Originally published in June 2019.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments