From relatively humble beginnings in Dublin, Thomas Moore became celebrated across Europe for his poetry, his prose, and most of all his Irish Melodies.

In his heyday, Thomas Moore became known as The Bard of Erin, with a prolific output of poetry. He also had a sensitive side, for when a literary critic castigated one of his poetic collections, which contained coy eroticism, he challenged him to a duel.

Fortunately, it never took place because police arrested both of them. However, the incident caused Moore to reflect on where his muse was taking him, so he took a new artistic direction, which resulted in musical compositions that radically transformed his reputation – The Irish Melodies.

The ten immensely popular collections of songs (1808 to 1834) contain such classical gems as The Last Rose of Summer, The Meeting of Waters, Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms, The Minstrel Boy, and Silent, O Moyle.

The publication was so successful that Moore was offered a contract of £500 a year (a huge sum in those days) for a further series, providing the 27-year-old author with his first regular income.

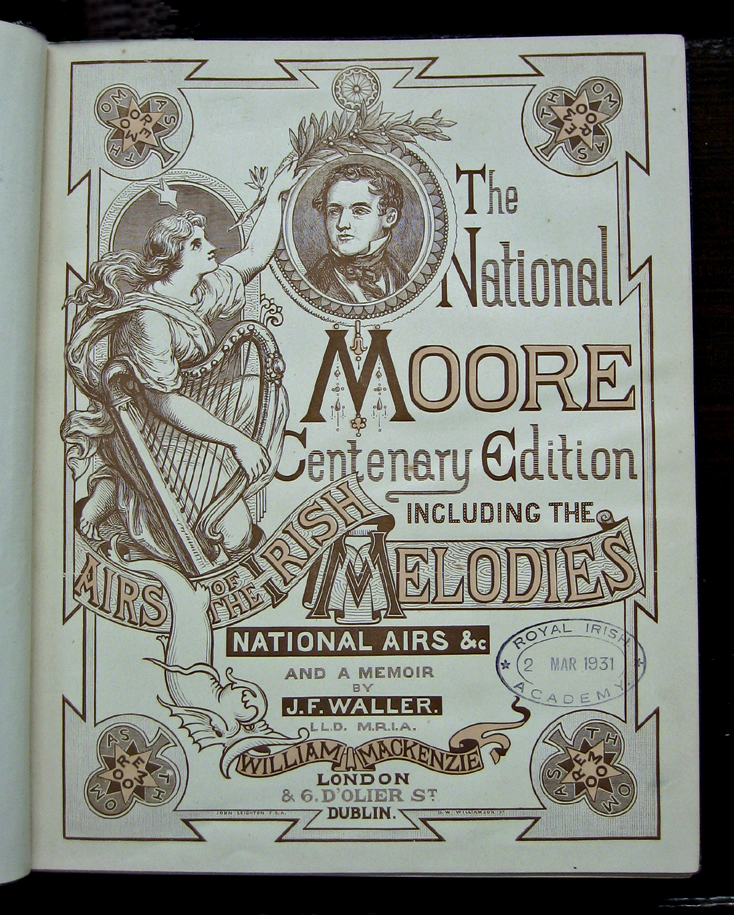

Cover of "The National Moore Centenary Edition including the Irish Melodies".

Despite their widespread popularity during the poet’s lifetime and right up into the 20th century, most of the 124 songs are unknown today. The unique effect of Melodies and Moore’s poetic genius can be attributed, in part, to the music he chose.

As well as popular appeal, Moore’s music and lyrics also captured the imagination of such august composers as Robert Schumann and Hector Berlioz.

From an ordinary Dublin upbringing, Moore moved to association with the 1798 Rebellion, patronage of his poetry by the Prince of Wales, friendship with Lord Byron, the leading English poet of the day, and flight to Europe over debts contracted in Bermuda. He also married and raised a family, but sadness walked in step with him on that front.

Moore was born in 1779 in Dublin’s Aungier Street, where his parents, John, a Kerryman, and Anastasia from Wexford, had a small grocery shop. A bright child, he entered Trinity College at age of 15, where he became friends with Robert Emmet. Because of this association, he was questioned by authorities at the outbreak of the United Irishmen’s uprising in 1798 but was allowed to graduate.

From there, he moved to London, where literary success came almost instantly. He dedicated his first book, a translation of odes by Greek poet Anacreon, to the Prince of Wales, and as he moved up in English society, he was granted a civil service post in 1803 in Bermuda by his patron Lord Moira.

This nearly proved Moore’s undoing, however, for he quickly became bored with his posting, and instead toured North America, where he met President Thomas Jefferson, before returning to London, leaving a deputy in his place. In 1811 Moore married Bessy Dyke, an actress he met in Kilkenny, and they had two daughters, both of whom died as infants. Then he learned his deputy in Bermuda had absconded, leaving a huge debt. Moore was responsible in law for it, but could not pay, so he fled to Europe to avoid jail.

He was helped financially by Lord Byron, and after several years spent mainly in Paris, was able to return to England. His pen was always active; as well as Melodies, he wrote biographies of playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan and United Irish rebel Lord Edward Fitzgerald.

To repay the kindness of Byron, he wrote a celebration of that poet’s life, and also classic historical fiction, Memoirs of Captain Rock, described as ‘a funny and scathing indictment of English misrule and Irish misdeeds’, which sold widely.

Sadly, personal tragedy continued in his life. His and Bessy’s third daughter died, and then their two young sons, both soldiers, also died; the effect apparently was to shorten Moore’s life, and he died at his home in Wiltshire in 1852.

His family grave is marked with a high Celtic cross, on which is inscribed Byron’s words: “The poet of all circles and idol of his own.”

Also inscribed on the cross are lines from one of Melodies:

Dear Harp of my country! In darkness I found thee,

The cold chains of silence had hung o’er thee long,

When proudly, my own island harp, I unbound thee,

And gave all thy chords to light, freedom and song.

As is well known and recorded, the harp was central to Moore’s work and muse. He was given a Royal Portable Harp, painted green with an interlaced decorative pattern of gold shamrocks, by renowned Irish harp-maker John Egan, which he played to accompany his singing.

In more recent times, Nana Simone and Nana Mouskouri both recorded The Last Rose of Summer in 1960s; Corrs released an instrumental version of The Minstrel Boy in 1995; song was performed by U2 on their 1997 tour; and Joe Strummer, formerly of Clash, did a version in 2001 and another version for hit movie Black Hawk Down same year. And there are those who believe that we have not heard the last of Moore’s melodies.

Comments