An Irish-language act should not be the cause for the collapse of talks in Northern Ireland.

Blaming the unionists for the last minute failure of the negotiations to re-establish the power-sharing administration in Northern Ireland (which collapsed over a year ago) is only telling half the story.

Yes, it was the unionist leader Arlene Foster who decided last week that the latest attempt had failed and ended the talks. But Sinn Féin is just as culpable, and probably more so. As we say over here, there's a pair of them in it.

For those of us on this side of the border, the very idea that a dispute about what we call "the cúpla focal" (Gaelic for "a couple of words,” which is all the Irish that most people here north or south can speak) would prevent the North having a government is absurd. It's particularly crazy right now because crunch time for Brexit is fast approaching, yet Northern Ireland, which will be badly hit and desperately needs an administration to speak up for its people, is voiceless.

Read more: 2018 is officially the year of the Irish language

#3Billboards #3Acts #HowComeArlene? 🅾️ pic.twitter.com/YhTS4h9RSv

— An Dream Dearg (@dreamdearg) February 20, 2018

Sinn Féin knows this is ridiculous which is why it was insisting last week that it's not just about the Irish language, but about "human rights" in general in the North, including unionist opposition to same-sex marriage and examining "legacy" issues from the conflict (which Sinn Féin intends will focus on state violence rather than its own crimes).

But it's the language that is the real sticking point, as Foster made clear last week. Sinn Féin wants a stand-alone Irish language act which would give Irish equal status with English in the North. It's about equality and parity of esteem for both traditions, they say.

Exactly what would be involved is unclear. A minimum probably would be dual language road signage in nationalist areas.

If it were applied on a general level, all state services would have to be accessible in Irish for those who want to use the language. Anyone who wanted to do their business in Irish rather than English in police stations, courts, post offices, public hospitals, etc., etc., would have to be accommodated.

Read more: Why the Irish language is not a political pawn and is important for Northern Ireland after Brexit

Ar an traen ar maidin in Iúr Cinn Trá. Jumping on the train this morning in Newry. Noticed local Bilingual signs. Hand on my heart, the English on these signs does not undermine my Irish identity. 👀 #SkyHasntFallenIn@dreamdearg #AchtAnois pic.twitter.com/nxJo4t1GGG

— Padaí Ó Tiarnaigh🅾️ (@ptierney89) February 22, 2018

How much this would cost is far from clear, with estimates ranging from £20 million to £100 million a year, or even more. What is clear is that it could involve state jobs for a small army of Irish speakers, most of whom would come from the nationalist community. The full cost would depend on how extensively state services through Irish would be made available.

Who would pay for this? It would be the long-suffering British taxpayer who already funds Northern Ireland with a transfer of £10 billion a year. But, of course, no one is asking British taxpayers whether they would be happy to do so.

There is some concern among unionists about this "waste of money,” as they see it, in a country where 100 percent of the people speak English. But it was not financial concerns that sank the talks last week. Instead, it was wider concerns among unionists that this was an attack on their Britishness and one that would be expanded and intensified in the future.

Knowing that many unionists, and particularly the majority in the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), had been concerned about this in recent months, DUP leader Foster had tried to fudge the issue in the negotiations with Sinn Féin.

The DUP did not directly oppose an Irish language act but insisted that if it did happen, equal status must also be given to the Ulster-Scots language and other customs that are part of the unionist tradition. To make this happen three acts would be introduced—an Irish language act, an Ulster-Scots act and a diversity act.

Read more: How North America will be celebrating the official year of the Irish language

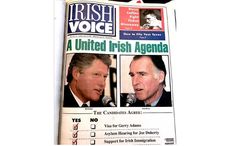

DUP leader Arlene Foster. Image: RollingNews.ie.

This fudge would have allowed Sinn Féin to say that they had got the standalone Irish language act they wanted, while the unionists could say they got three interlinked acts which also recognized and protected their culture and identity.

It seemed last week that a deal on that basis was almost done. But in the end, it collapsed, mainly because Foster could not sell it to the wider DUP party and its supporters.

Despite the acrimony after the collapse, neither side last week revealed the full details of how much had been agreed in the deal that was almost finalized. Foster has indicated that what was agreed in relation to the Irish language was limited. And in much of the media coverage that followed she was painted very much as the villain.

A fairer reading of what happened, however, would recognize that she had gone as far as she could, that she genuinely wanted the talks to succeed and the power-sharing administration to be re-established. Sinn Féin had pushed too far and the result was a collapse.

It should also be remembered that Foster has stated repeatedly that she accepts and respects the wishes of those who are supporters of Irish. She has visited Irish language schools and has taken the trouble to learn a few Irish phrases herself. But she is adamant that respect for Irish culture must also be matched by respect for unionist culture.

"We value the fact that there are Irish-language speakers living in Northern Ireland who want to speak in Irish and that’s fine, but they cannot impinge on the rights of those of us who do not speak the Irish language,” she said in an interview last week.

Reading some of the commentaries in the past week, one would be forgiven for thinking that Irish was being suppressed in the North and that there was no state support for the language when the opposite is the case. Around 40 all-Irish schools in the North and a few dozen more schools which have extra facilities for Irish are funded by the state.

Read more: Ian Paisley’s widow slams Arlene Foster and DUP over Stormont stalemate

Scaifte iontach i láthair ag agóid @dreamdearg - fanfaidh muid ar na sráideanna go dtí go bhfuil #AchtAnois

— An Dream Dearg (@dreamdearg) September 28, 2017

Still #DeargleFearg 9 months on pic.twitter.com/hN4ktChA9c

One might also get the impression from the commentary that there is a large number of active Irish speakers in the North who are clamoring to have their language rights vindicated. Again, the opposite is the case.

The most recent census in the North showed that just six percent of the population claimed to have "some knowledge" of Irish (which probably does not extend much further than “Tiocfaidh ar Lá”) and less than one percent (0.2 percent) saying they used Irish as their language at home.

It is because of this reality that unionists claim that Sinn Féin is cynically using Irish—" weaponizing the language" as they put it—to generate a bogus sense of grievance while at the same time undermining English and the unionist tradition. In vox pop TV interviews on the streets in the North last week, ordinary unionists said it was the start of a "culture war" which is out to destroy their British identity.

Several leading Sinn Féin figures last week sanctimoniously made the point that they are simply looking for the same rights that exist in Scotland and Wales where British legislation protects their minority languages. But it's a bogus comparison.

In Wales, many people genuinely do speak Welsh every day and those who speak English don't feel under any pressure. It's not comparable to the North, where language is seen as a badge of identity in a deeply divided society with a recent history of extreme violence.

Sinn Féin also drew attention to the fact that in the 2006 St. Andrews Agreement (which set the parameters for devolution in the North) there was a commitment by the British government to consider introducing an Irish language act in the North. This was part of the efforts to ensure equality under a Northern Ireland executive but it was never introduced, not least because the unionists said they had never agreed to it.

British and Irish Governments SIGNED this agreement 👇🏽 pic.twitter.com/gZtbZU5Uss

— An Dream Dearg (@dreamdearg) February 15, 2018

The reality is that Sinn Féin's elevation of the Irish language to the level of a critical demand is a recent happening. It was way down the Sinn Féin agenda during their years of power-sharing, despite pressure on them from the Irish language lobby in the North.

Given all this, it's hard not to be suspicious that Sinn Féin is using the language issue now because it suits them for political reasons. The reality is that, although there is an enthusiastic Irish language lobby in the North, it is a tiny fraction of the nationalist population. In this, the North is no different from the south where we have a vibrant but numerically small group of Irish enthusiasts who send their kids to all-Irish schools, etc.

Vast amounts of money have been spent on the attempt to resurrect the Irish language in the south over the decades, the Irish language TV station TG4 being just one example. But despite all this, our everyday language remains English and only a tiny section of the population can speak Irish with any fluency. (That does not stop people claiming on census forms to be Irish speakers but the reality is exposed whenever people are faced with holding a conversation in Irish and after the "cúpla focal" suddenly go dumb!)

Are Sinn Féin hypocrites if their leaders Michelle O'Neill and Mary Lou McDonald can't speak Irish? Image: RollingNews.ie.

And talking about going dumb, it was revealed last week when a reporter from the Irish language TV station TG4 asked Sinn Féin President Mary Lou McDonald and Sinn Féin leader in the North Michelle O’Neill a question in Irish at a press conference. Both of them froze like rabbits caught in headlights and could not answer. They had to be rescued by a senior Sinn Féiner who is fluent in Irish and spoke for them.

It's at such moments that the truth about all this is revealed. The truth is that, like in the south, the vast majority of the population is unlikely ever to have more than the "cúpla focal." And no Irish language act is going to change that.

One wonders how much the ordinary Sinn Féin supporters really care about the Irish language. So why, you might ask, is it being used to stop the North having the power-sharing administration it so desperately needs?

Do you think Northern Ireland needs an Irish-language act? Let us know your thoughts in the comments section, below.

Comments