175 years ago this month, my family took part in a time-honored tradition - for their first time ever.

On August 3, 1850, my third great-grandparents and their four children were counted in the US Census.

We all know that national undertaking. Taken every decade, it’s a source of pride for many, ensuring, among many things, representation in this self-governing experiment of ours now in its 250th year.

Not to mention the census as a foundation for discovering from whom and from where we come.

Back then, my family lived in a village called Willow Grove, 14 miles north of the Birthplace of America as a matter of fact.

It’s along the Old York Road, which ran all the way from Philly to the place they had arrived three years earlier—New York.

That’s when the Carolans had found the means to flee the greatest humanitarian disaster of that century—the colonization, occupation, starvation, and arguable genocide of an entire country: Ireland.

The same starvation and genocide that is being allowed to happen again, today, shamefully in Sudan and Gaza.

The difference being that today, many can’t escape.

When you escaped in the mid-19th century, though, you were allowed to land on our shores easily, softly—not always with arms to embrace you, but with no questions asked.

How lucky we were.

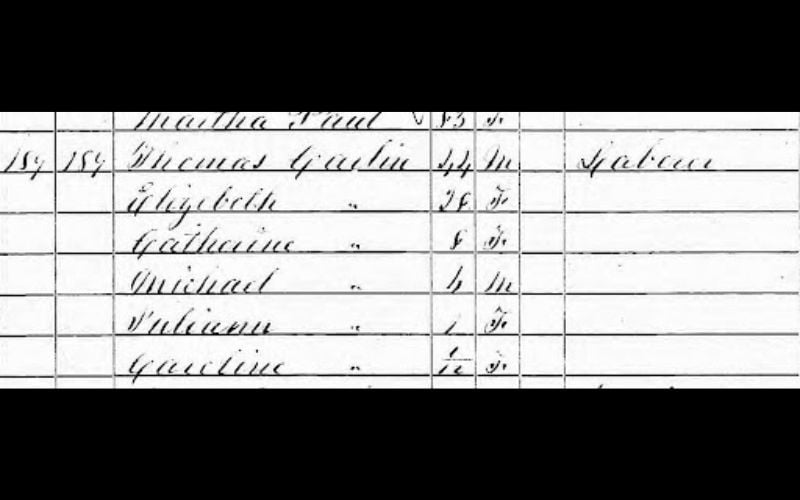

36 months after the Carolans arrived, almost to the day, Assistant Marshal Richard Eckroyd Yerkes did ask a few questions. But not about our citizenship status.

At dwelling number 189, the marshal, who was 41 years old, misspelled our surname as “Carlin” but correctly captured our first names, ages, and birthplaces.

And in perfectly-ordered cursive handwriting on a large paper roll that, 143years later, I would touch with my finger at the National Archives in Washington, DC:

Thomas, age 44, born Ireland

Elizabeth, 28, Ireland

Catherine, 8, Ireland

Michael, 4, Ireland

Juliann, 1, Penn.

Caroline, 1/12 or one month, Penn.

Michael is our great-great-grandfather.

As an ardent genealogist, I’ve connected with a descendant of his elder sister Catherine, who coincidentally lives near me in Western Massachusetts.

Fourth cousins: Joanne Pinatel and Michael Carolan. Joanne’s great-great-grandmother, Catherine Carolan, was the older sister of Michael’s great-great-grandfather and namesake. The two were young children, aged 4 and 2, when they arrived at the Burling Slip at 78 South St. in New York City on the Packet-ship Patrick Henry on July 27, 1847.

And a few years ago, I took my father to the approximate spot where our ancestors resided on the very day they were captured in print. We were excited to find anything there, much less two memorials, not to our great-grandparents, of course, but to the inn and manor that stood nearby. The markers were upon freshly-cut grass next to a very paved-over, bustling automobile intersection. The wonders of technology and assiduous sleuthing.

By the time the assistant marshal arrived at the intersection where our first home once stood, our family, like most, had experienced the joy—in our case, the births of Juliann and of Caroline—and the heartache . . . of displacement. Two children with whom Thomas and Elizabeth had arrived were no longer with them.

In 1847, the manifest of the Packet-ship Patrick Henry recorded 13-year-old Bessy and one-year-old Annie. So young, Annie may have been victim of disease caught on the voyage. Her oldest sister’s story was more complicated.

By all accounts, she was the product of a relationship her father had with a woman prior to his marriage. On her baptism record, immediately after noting the date, the priest of the parish of Kells, Co Meath, wrote, “illegitimate.”

On the streets of a new and strange country, the teenager may have died of illness or, more likely, left on her own. In the 1860 census, an Elizabeth (born in 1834) works as a servant in a private home in Hempstead, Queens, New York.

How her father and half-siblings made their way toward the Quaker City, and when, is anyone’s guess. Thanks to an altruistic network of the Religious Society of Friends, the family perhaps had connections as they went from Drogheda to Liverpool to New York, which meant all they had to do was make their way to Willow Grove.

The author and his father, William George Carolan, in August 2017, at the site of their ancestor’s first home in the U.S. circa 1850, in the center of Willow Grove, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, at the intersection of Easton Road, Park Avenue and the historic York Road.

What’s clear is that the man who visited my family three years after their arrival was himself a Quaker. According to local histories, the Yerkes had come from Germantown, leaving a generations-long footprint back to the 1600s.

Richard was the father of six children and the proprietor of a cotton mill with $8,000 in real estate value. We know because he enumerates himself as the final inhabitant on his census pages.

He lived two miles east of Willow Grove in the aptly named village of Yerkesville, at today’s Papermill and Terwood Roads. Several mills, houses, a store, a blacksmith shop, and a school stood at Yerkesville; today, a few still do, according to the Upper Moreland Historical Association.

As an assistant marshal of the Census Bureau, Richard Yerkes had taken an oath to be part of the country’s seventh effort to document its people since its founding. Required by law to visit every home personally to collect information directly from the inhabitants, the marshal was to act with courtesy and professionalism, and adapt his inquiries for clarity, “particularly for foreigners and those with limited education.”

At the time he visited house 189, Mr. Yerkes had been riding his horse between farmhouses and walking door to door in the more thickly-settled areas for a little over a week . His region was “Mooreland,” named after Nicholas More, the London physician who accompanied William Penn across the Atlantic and, in 1682, was granted nearly 10 acres here that grew to 10,000. (Today, it’s divided into two townships — Upper and Lower Moreland.)

In 1850, it was one 16 square-mile area that would take Assistant Marshal Yerkes precisely one month, from July 24 (my father’s calendar birthday) to August 24, to document, in 56 pages, the 410 houses in which were 2,352 free inhabitants— the document is available online today.

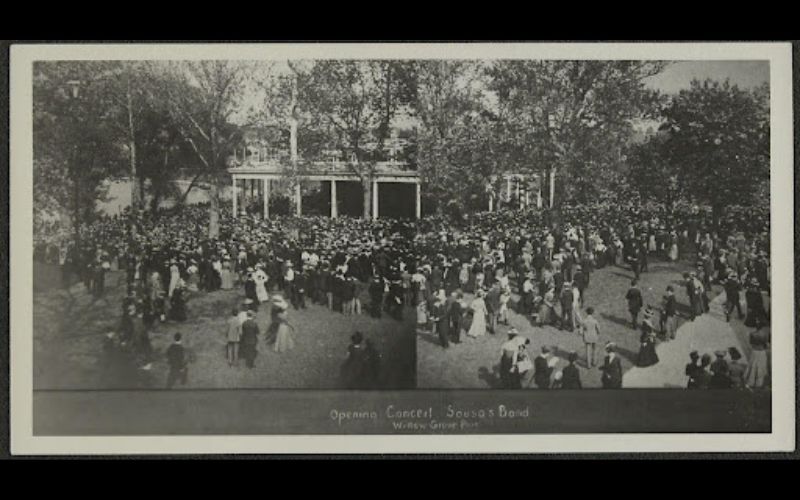

My ancestors’ unremarkable village would become, a half century on, a remarkable place indeed. Legendary for its amusement park and as the “Music Capital of the World,” thanks to the son of Portuguese immigrants, the composer and marching band conductor John Philip Sousa. He performed regularly for a quarter of a century, his iconic American march, "The Stars and Stripes Forever," first played here in 1897.

Opening Concert, Sousa’s Band. Photograph from early 20th century taken at Willow Grove Park near where the Carolan family lived a half century before. (Library of Congress)

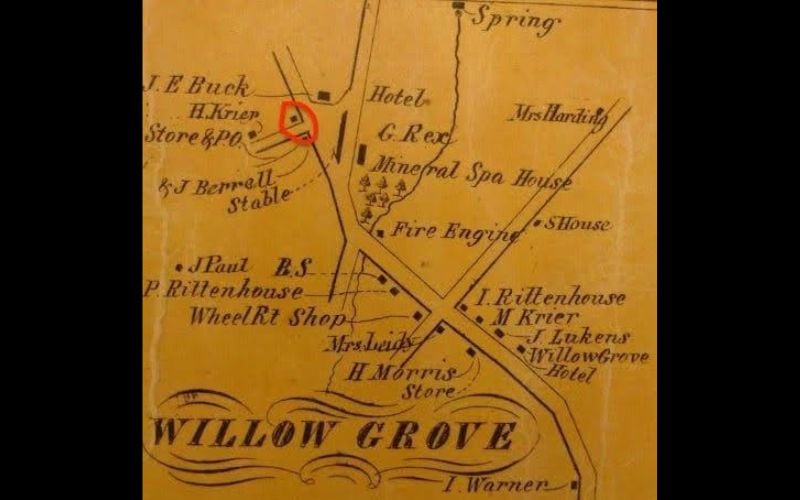

But on that Saturday a half-century before, there was a small dwelling-house between the historic Red Lion Inn, called the Jacob E. Buck Hotel, and the Manor of Moreland itself, the stone mansion for which the region was named.

The Carolans lived between the more noble places, in what was likely an original structure on the Manor property, built of logs and used for a time as a schoolhouse, according to Heather Greenleaf, an archivist with the Upper Moreland Historical Association. They may have rented from Henry Krier, a farmer who lived in the Manor house with his wife and mother-in-law, a descendant of the original settlers.

Assistant Marshal Yerkes asked a number of questions of Thomas and Elizabeth, who were marked as being able to “read and write.” Their older children Catherine and Michael “attended school.” What was their “profession, occupation or trade”? Nothing for Elizabeth. Thomas was noted, “laborer.”

The Carolans would have seen the Manor of Moreland (no longer standing) out their front door in the first place they lived in their new country. A historical marker stands on the spot today. (Photograph dated to 1950. Courtesy: Upper Moreland Historical Association.)

In 1992, on Anna Maria Isle, Florida, my grandfather’s sister, Ann Marie Carolan Moerk, told me that her grandfather, the Michael in our narrative, was a blacksmith and a horseshoer, as was her great-grandfather, Thomas—the “laborer” in Willow Grove. I would locate them all on the census at the National Archives the following year.

The Carolans chose the right spot to settle: The Old York Road was the I-95 of its day. With five daily stagecoach lines, it connected Philly with New York City. Work was plentiful. Just next door was that hotel, three-stories with 23 rooms and a long stone stable for up to a hundred horses. Nearby, the Mineral Springs Inn had similar capacity, and just around the corner was the forge of the noted village blacksmith, Isaac Rittenhouse.

Willow Grove was a day’s journey from Center City for a team of horses pulling stages or loaded wagons. The roads were bad, passengers weary, horses injured or slow, or needing rest or re-shoeing. The place was busy with foot, horse, and wheel traffic, in other words, a living wage for a blacksmith “laborer” like my third great-grandfather.

Circa 1857. By Shupe & Kuhn. The red circle is the approximate location of the Carolans’ first home, likely a vacant former schoolhouse constructed of logs. (Courtesy: Upper Moreland Historical Association)

I wonder whether Thomas and Elizabeth imagined that they would, over the next decade and a half, produce six more children who, all told, would produce some 31 grandchildren and multiply exponentially, like every other emigrating family across the ages, given the chance.

What’s as interesting to me as how we came to be ... is our Quaker connection.

As people, Quakers and the Irish were related: William Penn himself, exiled to Ireland in 1666, converted there. And in that very hour of my family’s first enumeration, the Society of Friends was supplying what would today be millions of dollars in direct aid to the refugees of the Great Hunger.

And not even two years later, another Quaker, an elderly man named George Spencer and his wife Mary, would play an even more significant role in our origin story.

By 1860, the couple had taken in a 19-year-old African American woman— undoubtedly saved on the Underground Railroad — named Elizabeth Moore as well as two Carolan children, Michael, age 15, and Martha, age eight, to live alongside them in their farmhouse a mile to the northeast of Willow Grove.

This would alter our family’s course for generations to come, which is another story altogether. Their farmhouse—featured on an episode of the "Ghost Hunters" television series—is another story as well.

Note: This is among a series of forthcoming articles about the Carolan family.

Michael Carolan was born in Kansas City, Missouri. Today he lives in Dwight, Massachusetts, with his wife and cat. He has two children, three siblings, and eleven nieces and nephews. He writes for the 200-year-old Massachusetts daily, The Springfield Republican. You can see more of his work on his website, Substack, and Medium pages.

Special thanks to researchers, including Heather Greenleaf, of the Upper Moreland Historical Association.

See also: Éireann’s exiles — reconciling generations of secrets and separations, and On This Day: A Famine ship carrying my Irish ancestors arrives in New York City in 1847.

Sources:

- Ireland, Catholic Parish Registers, 1655-1915, National Library of Ireland, ancestry.com

- New York, US Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, ancestry.com

- Momorella, Edward. A Brief History of Willow Grove.

- Thomas, Joe. A Synopsis of the History of Moreland Township and Willow Grove. 2000.

- Philadelphia Area Early Landowners Resources

- Upper Moreland Historical Association: Trail of History.

- US Census, Moreland Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. 1850 and 1860.

- US Census, Hampstead, Queens, New York, 1860.

Comments