On May 22, 1998, in the first all-island vote in Ireland since before partition, the people overwhelmingly supported the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement’s framework for peace, equality, tolerance and mutual respect.

At the “20 Years of Peace” Conference hosted earlier this year in New York by Co-operation Ireland and IrishCentral, Irish Tanaiste Simon Coveney said that was the day “the political agreement became the people’s agreement.”

Over ninety-four per cent of the voters in the Republic of Ireland endorsed the Agreement. In doing so, they approved the Irish government’s plans to amend Articles II and III of the Irish Constitution and renounce constitutional claims to Northern Ireland.

20 Years of Peace Celebration Event - Keynote SpeechPosted by IrishCentral.com on Thursday, February 22, 2018

Eighty-one percent of the electorate turned out to vote in Northern Ireland, and seventy-one percent of those voters endorsed the Agreement. Support for the Agreement in the nationalist community, however, nearly doubled the support it received in the unionist community. The Agreement recognized “the right to self-determination,” but stipulated it could only be exercised “on the basis of consent, freely and voluntarily given, North and South.”

The principal of consent gives the people of Northern Ireland the right to control their destiny and determine their future. For those who aspire to unification with the Republic, the Agreement makes it possible by providing a democratic roadmap for gaining a united Ireland.

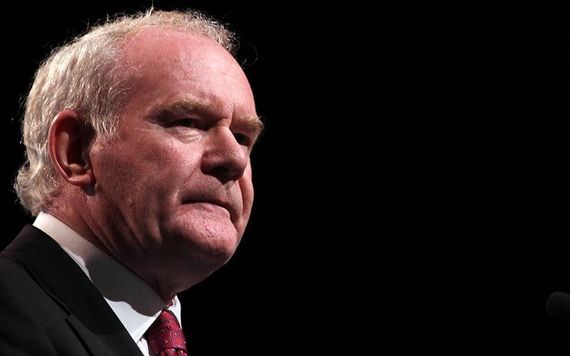

When the late Martin McGuinness referred to “the nation-building stage of the struggle,” he was speaking about creating a new, inclusive, pluralistic and prosperous Northern Ireland. A society in which the identities and traditions of nationalists and unionists are forged into a diverse and shared identity, grounded in equality and a genuine partnership between communities. Until this happens, a border poll will be a divisive exercise.

Identity is fundamental to how people view themselves as individuals and as members of a group. Identity is a particularly powerful factor during conflict in determining how groups relate to each other. The death of nearly 3,600 people during the Troubles impacted all levels of society. It left Northern Ireland deeply scarred. Generally, nationalists maintain one narrative about what occurred and who is to blame, and unionists hold another. These separate narratives reflect an identity conflict that continues to haunt Northern Ireland, as demonstrated by governmental dysfunctional and political polarization.

One way identity issues are being resolved today is through grassroots cross-community work. Elizabeth Elliott, who was a restorative justice teacher and author, noted that “healing harms is inextricably linked to relationships.” The bridges connecting communities being built by community workers make a significant positive contribution to Northern Ireland’s future.

Another way to transform society is to implement an honest, searching and human rights compliant truth recovery process. Essential elements would include investigating legacy cases, allowing individual stories of loss and suffering to be presented in an official forum, and providing answers about what happened and why. The Agreement did not explicitly call for that. But the Agreement did call for the promotion of mutual understanding of the hurt suffered by both communities and development of “respect between and within communities and traditions.” A process aimed at capturing and preserving the truth will enhance that.

Story-telling and dialogue conjoined with empathy and acknowledgement will build relationships and heal societal wounds, even in the face of the grievous harm, tragic loss and severe pain suffered by both communities.

When individual stories are collected and shared, people gain insight and begin to appreciate that others may have had experiences similar to theirs and suffered in the same way they did. This fosters a shared understanding of the truth and what is needed to recover. It nurtures greater respect among and between communities. When people see they have a common bond with members of another group, it changes the mindset of “us against them” to one of “we are in this together,” which is the mindset required for a society that seeks a shared identity and shared vision of the future.

In his second Inaugural Address, delivered a month before the end of the U.S. Civil War and his assassination, President Abraham Lincoln highlighted the formula he would employ for healing the nation with these immortal words: “With malice toward none, with charity for all.” Lincoln’s generosity of spirit “to bind-up the nation’s wounds” was not followed. As a result, more than 150 years after his death, the U.S. is still dealing with unresolved issues related to that war.

To avoid a similar fate, Northern Ireland must address its past before the passage of time ruins any effort to do so. That makes it especially important for the government’s recently announced public consultation process on proposals for dealing with the legacy of the Troubles to achieve a meaningful outcome.

Addressing the legacy of the past is indispensable to constructing the shared identity envisioned twenty years ago when the framework for peace, equality, tolerance and mutual respect in the people’s Agreement was overwhelmingly affirmed.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments