Americans with parents or grandparents from Ireland apply for citizenship to honor their ancestors and show their love for Ireland. To end this would damage the strong bond between Ireland and the United States.

Editor's Note: The following opinion piece was submitted to IrishCentral by genealogists Kate and Mike Lancor who live in New Hampshire. The Lancors have previously contributed a number of articles to IrishCentral about researching Irish roots and ancestry.

Ronan McRea’s editorial in the Irish Times on July 14 states, “Irish citizenship practice was designed at a time when it was inconceivable that a larger number of U.K. and U.S. citizens would ever want to take up the option of Irish citizenship in order to come and live in Ireland.”

McRea is referring to the current practice of allowing individuals who had a grandparent born in Ireland to apply for Irish citizenship by descent. To do so, an applicant needs to provide to Dublin officials the baptism, marriage, and death certificates for the grandparent who was born in Ireland; the birth, marriage, and death certificates for the applicant’s parent, and then the applicant’s birth and marriage certificate if appropriate. In other words, the direct line of descent needs to be confirmed with original certified copies of all the records mentioned above.

Ronan McRea goes on to suggest that, “The Irish authorities may want to reconsider if there is a fairer, more targeted and more cautious means of nurturing links with the diaspora than granting full citizenship on the basis of tenuous blood links.”

Interestingly, he also states that is not likely to see large numbers of U.S and U.K. citizens apply for Irish citizenship in the immediate future and move to Ireland.

A bronze dramatic sculpture at the foot of Croagh Patrick in Murrisk on Clew Bay in Co. Mayo depicts a “Coffin Ship” with skeleton bodies in the rigging.

The two of us are genealogy researchers and have a business called Old Friends Genealogy. As a result, we have helped numerous members of the Irish diaspora in the U.S. go through the process of applying for Irish citizenship based on descent. We cannot speak for U.K. citizens, but our experience with Americans is that they apply for Irish citizenship so they can proudly display their love for Ireland and in honor of their grandparent who was born in Ireland. They do not apply for Irish citizenship with the intent of moving to Ireland.

Ronan believes that Irish authorities should change their citizenship process to avoid a potential situation that he himself says is not an immediate problem. The latest census taken in Ireland was in 2016 at which time Ireland’s Central Statistics Office (CSO) stated that there were over 4.4 million persons living in Ireland. Of that number, the CSO says there were 17,552 Irish Americans holding dual-citizenship living in Ireland.

In other words, Irish Americans holding dual-citizenship made up 0.37% of Ireland’s population in 2016 with non-Irish Americans making up 99.63% of Ireland’s population!

It is clear t us that the current citizenship by descent practice in Ireland is not posing a threat to Ireland’s democracy or sovereignty. Ronan states that given Ireland’s relatively small size compared to Britain and America, the consequences of continuing to grant citizenship by descent could be significant. He ends his editorial by stating, “After all, if 1 percent of the Irish population moved to America, few in the U.S. would notice. But if 1 percent of the U.S. population moved to Ireland, the newcomers would be almost half the population of the State.”

This Famine Graveyard is near the edge of Donegal Town in Co. Donegal. A memorial plaque reads, “In loving memory of those who died of hunger and disease in the Great Famine of 1845-1848 and were buried in this cemetery.” Millions of Irish American diaspora are descendants of Great Famine emigrants and do not qualify for Irish citizenship.

We are two of at least 36 million Americans who claim Irish as their primary ethnicity. Ronan leaps to the conclusion that 1 percent (3.6 million) Irish Americans could apply for Irish citizenship with the intent of moving to Ireland. That conclusion is nothing short of absurd. Like many, many of those 36 million Americans, we are descendants of Irish men, women, and children who emigrated to the U.S. during the Irish Potato Famine or the Great Hunger. Our Irish ancestors were our great grandparents, not our grandparents. Like so many Americans of Irish descent, we do not qualify to apply for Irish citizenship.

Furthermore, let's take a look at the mathematics involved in order for one to apply for Irish citizenship based on having a grandparent born in Ireland. One’s parent would have to have been born in the U.S. to a grandparent born in Ireland. Most Americans who apply for Irish citizenship by descent are 60 years of age or older with a grandparent born in Ireland in the late 1800s or early 1900s. To speculate that millions of Americans who are part of the Irish diaspora will soon be applying for Irish citizenship so they can move to Ireland is not remotely realistic.

We have written articles for IrishCentral promoting the very strong bond between Irish Americans and Ireland. That bond has been forged and strengthened by both Irish Americans and the people of Ireland. Changing Ireland’s process for citizenship of Irish Americans by descent at this point in time is certainly not necessary and could only serve to weaken the very close bond shared between the two countries.

Read more: The Great Hunger and Ireland’s lasting bond with the US

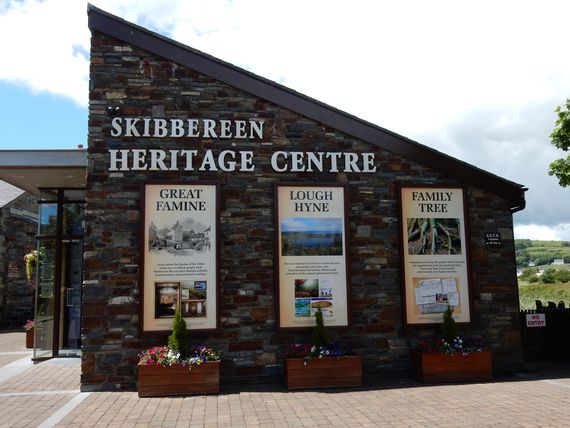

The Skibbereen Heritage Center in Co. Cork houses the Great Famine, or Great Hunger, Commemorative Exhibition. Skibbereen and surrounding areas were very badly affected losing up to a third of their population to hunger, disease and emigration. In the words of Johnny Cash, “We miss the river Shannon and the folks at Skibbereen.”

Like many Americans, we had planned to once again travel to Ireland this summer to spend time taking in Ireland’s most fantastic scenery and visiting again with long-lost cousins and friends we have spent time with over the past decade. We will greatly miss spending time in Ireland in 2020, but have secured our plane vouchers with hopes of making our next trip in 2021.

In the words of Johnny Cash, “I (we) close my (our) eyes and picture the emerald of the sea, From the fishing boats at Dingle to the shores of Dunardee, I (we) miss the river Shannon and the folks at Skibbereen, The moorlands and the midlands with their forty shades of green.”

*Kate and Mike Lancor live in Moultonborough, NH, U.S. and have traveled to Ireland numerous times. They run a genealogy search business and can be reached on their website or by emailing [email protected]. You can also visit their Old Friends Genealogy Facebook page. If you have “hit a brick wall” or simply don’t have time to “chase” your ancestors, then send them an email to see if they can help!

Read more: Unwanted American tourists being treated like lepers abroad

Comments