Among the many Irish and Irish American military heroes of U.S. history whose exploits have become lost to most Americans in modern times, we now add the name of War of 1812 hero George Croghan.

It's not surprising that George chose a military career. His father, William, born in Dublin in 1752, had been a major in the 8th Virginia Regiment during the American Revolution. He fought at the battles of Brandywine, Monmouth, and Germantown, lived through the horror of Valley Forge while serving on the staff of Baron von Steuben, and took part in the crossing of the Delaware and the victory at Trenton. He was present at the surrender at Yorktown. George's famous maternal uncles were Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Revolutionary War hero General George Rogers Clark.

George was born at Locust Grove farm in Louisville, KY on November 15, 1791. Shortly after he graduated from William & Mary College in 1810, George gave up his law studies and enlisted in the army.

In November 1811, he fought against the Indian forces of Tecumseh with William Henry Harrison's army at the Battle of Tippecanoe. Though he served there as a private on Harrison's staff, he managed to impress Harrison so much with his bravery that he was promoted to captain.

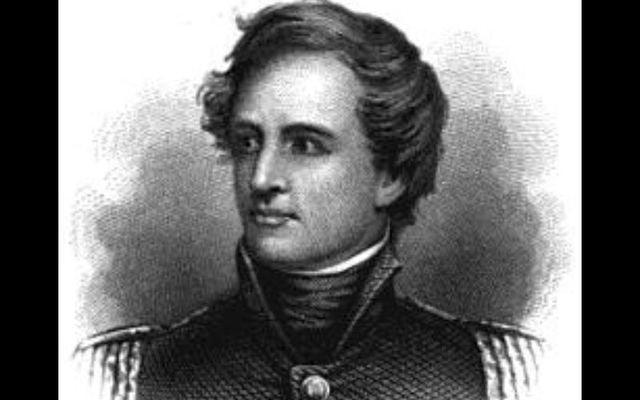

(Right: Lt. Col. George Croghan, painted in 1816, by John Wesley Jarvis.)

Read more

When the War of 1812 began, Croghan was in position to help defend the American Northwest in Ohio. In May 1813, Croghan was part of the U.S. Army forces in Fort Meigs near present-day Perrysburg, Ohio, during a failed siege by the British under General Henry Proctor and their Native American allies under Tecumseh. Once again, George's bravery in combat was on display as he led a raiding party out of the fort against a British battery. He was rewarded with yet another promotion to major.

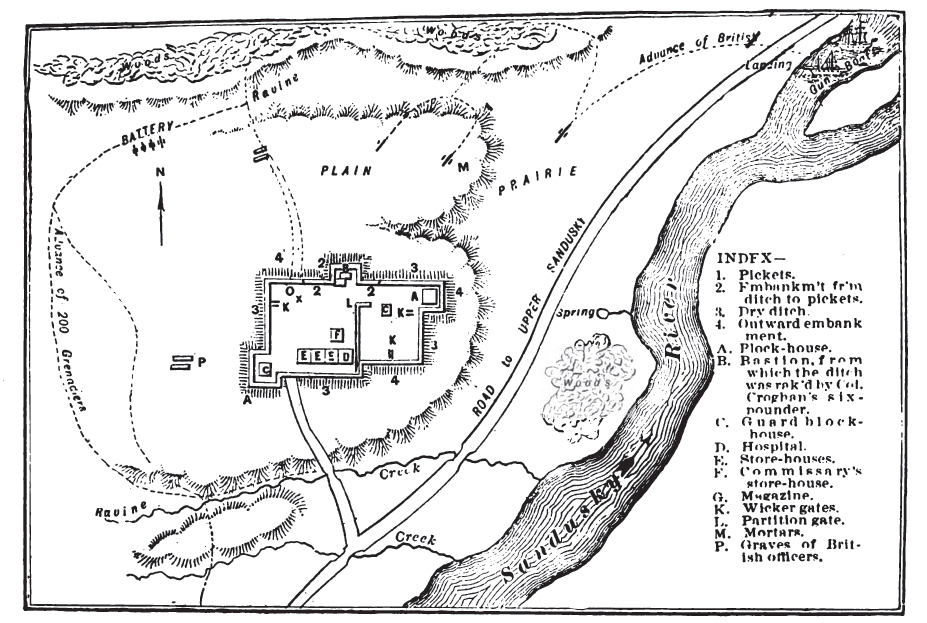

Croghan was just 21 years old in early July when Harrison placed him in command of a crucial position, Fort Stephenson on the Lower Sandusky near present-day Fremont. The fort guarded Harrison's headquarters and supplies at Fort Seneca and the water route from Pittsburgh to Detroit. Croghan had just 160 men and one artillery piece to defend the position. When the British under Proctor began to advance on the fort, Harrison, believing Proctor's force to be larger than it was, ordered Croghan to destroy the fort and retreat.

Incredibly, the young major sent this message back to the hero of Tippecanoe:

"Sir, I have just received yours of yesterday, 10 pm., ordering me to destroy this place and make good my retreat, which was received too late to be carried into execution. We have determined to maintain this place, and by heavens, we can."

The future president was not amused by this sort of disrespect from a 21-year-old and had Croghan arrested and returned to Fort Seneca. Astonishingly, the young Irish American officer talked his way out of the trouble. His first claim was that his defiant wording was caused by the fear that the enemy might intercept the message. After explaining his improvements to the fort's defenses, including a dry moat, and exhibiting his youthful confidence that he could succeed, Croghan convinced Harrison to restore him to command and attempt to hold the fort. Thus, a combined force of 1200 British regulars and Native Americans was bearing down on Croghan and his tiny force, which had one lone six-pound artillery piece nicknamed "Ol’ Betsy.”

Shortly before the battle, Croghan, realizing it might be his last chance to ever speak to him, wrote to his father:

“I will defend this post till the last extremity. I have just sent away the women, the children, and the sick of the garrison that I may be able to act without encumbrance. Be satisfied. I shall, I hope, do my duty. The example set me by my Revolutionary kindred is before me. Let me die rather than prove unworthy of their name.”

On August 1, General Proctor arrived and surrounded the tiny fort with approximately 500 British regulars and 700 Indians. He sent a white flag demanding surrender. Croghan had no intention of surrendering. There had already been several incidents in the region of the British being unable to stop their Indian allies from slaughtering many prisoners. There would be no surrender. “When this fort is taken, there will be none to massacre,” said the youthful major in a reply that was at once both defiant and an indictment of the fate of previous American prisoners.

Proctor’s gunboats on the Sandusky and his field artillery opened fire at the fort but with little effect. Croghan occasionally returned fire with “Ol’ Betsy,” moving its position around to make the British believe he had several pieces. The British barrage had little effect on the fort, partly because Croghan noticed they concentrated on the northwest corner and reinforced those walls with bags of sand and flour. He gambled that the main assault would come there the following day. And Croghan positioned “Ol’ Betsy” in the corner blockhouse where it could cover the dry moat.

A contemporary diagram of Fort Stephens and the attack.

In the late afternoon of August 2, the assault began. The 41st Regiment of Foot made the main assault under their commander, Lt. Colonel William Shortt. With the British cannon roaring and the smoke from them obscuring the vision of the defenders, the defenders did not see the attacking force until they were very close to the walls. But they were attacking the northwest corner, exactly where Major Croghan had anticipated and put his most robust defense.

As the British reached the dry moat, Shortt led them into it, yelling, “Come on my brave fellows, we will give the damned Yankee rascals no quarter.” But the “Yankee rascals” would not need to ask for quarter. Croghan had held his fire until they were very close. He unleashed the muskets of his infantry and let loose down the moat with “Ol’ Betsy.’ The effects of this combination were devastating. The British forces were riddled. Shortt fell mortally wounded, and dozens of others screamed in pain all around the survivors.

It was all over in about 30 minutes, with very few of the soldiers of the main assault who had gotten into the moat managing to retreat. There were about 25 dead and a similar number of seriously wounded lying there. The Americans suffered only one killed and seven wounded, and none of them seriously. The lone American KIA was a 14-year-old boy who had his arm torn off by a cannonball. Major Croghan took pity on the suffering British wounded who were crying out at the base of the fort. He had buckets of water lowered down to them in hopes of relieving their suffering.

So shattered were the British forces by this bloody repulse that Proctor had no thought of renewing the assault; he retreated to Fort Detroit. It was one of the most lopsided victories in U.S. military history and one of the first land battles of consequence that the Americans had won, raising the country’s morale. Croghan was hailed as the “Hero of Fort Stephenson, “earning another battlefield promotion to Lt. Colonel.

Back in Louisville, his famous uncle, George Rogers Clark, declared, “The little game cock, he shall have my sword.” Croghan himself modestly wrote to his father, “I am not worthy of so high a command, but since my government have honored me . . . I stand pledged to use my utmost endeavors to become worthy of it.”

On learning of the victory, Gen. Harrison gave himself some credit at the same time as he praised Croghan, saying:

“It will not be among the least of Gen. Proctor’s mortifications to find that he has been baffled by a youth who has just passed his twenty-first year. He is, however, a hero worthy of his gallant uncle, Gen. George R. Clark. And I bless my good fortune in having first introduced this promising shoot of a distinguished family to the notice of the government.”

Croghan later commanded the failed attempt to recapture Mackinac Island from the British and then was sent south. At the Battle of New Orleans, he served another future president, General Andrew Jackson, and they became friends. He would make New Orleans his home for the rest of his life, leaving the army and becoming postmaster there for a time.

In 1825, he rejoined the army, and Jackson appointed him inspector general in 1829, a post he’d hold for 20 years. Congress issued a gold coin commemorating Croghan’s victory at Fort Stephenson In 1835.

The front of the gold coin commemorating Croghan’s victory.

Croghan’s post-war life was not a happy one. He and his wife Serena had four children die in infancy. He had a drinking problem later in life, perhaps rooted in those tragedies. They had marital issues, which those drinking problems may have caused, and separated. When it was suggested to President Jackson that Croghan be brought up on charges for his drinking, he slammed his fist on his desk and declared, “George Croghan shall get drunk every day of his life if he wants to, and by the Eternal, the United States shall pay for the whiskey.”

Croghan’s last service to his country would come in the War with Mexico, on the staff of General Zachary Taylor (Croghan’s 3rd future president commanding officer). Whatever personal flaws George may have had later in life, when his country called, he did not hesitate to defend it.

On January 8, 1849, Croghan died in New Orleans during a cholera epidemic that also killed former president James K. Polk. He was buried in the family plot at Locust Grove in Louisville. On August 2, 1885, which has been celebrated as “Croghan Day” in Fremont since 1839, a monument was dedicated at the site of Fort Stephens. On August 2, 1906, Croghan’s remains were brought from Louisville and interred at the monument’s base.

Croghan’s victory at Fort Stephenson may now seem minor. Still, in that one shining moment in 1813, he faced a challenge in command of an important position defending his country that very few 21-year-old soldiers have ever encountered before or since. And so, fittingly, George Croghan rests today in the place he famously defended, with “Ol' Betsy" endlessly standing guard over the body of her old commanding officer, who in this one spot remains forever young.

Where Crogan his laurel chaplet earned

and Freedom's foes a lesson learned

A shaft memorial is deserned,

The soldier's benison.

--- From the poem "Fort Stephenson," by Captain Andrew Kemper

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments