“I spy with my Irish eye, someone beginning with ‘B’”

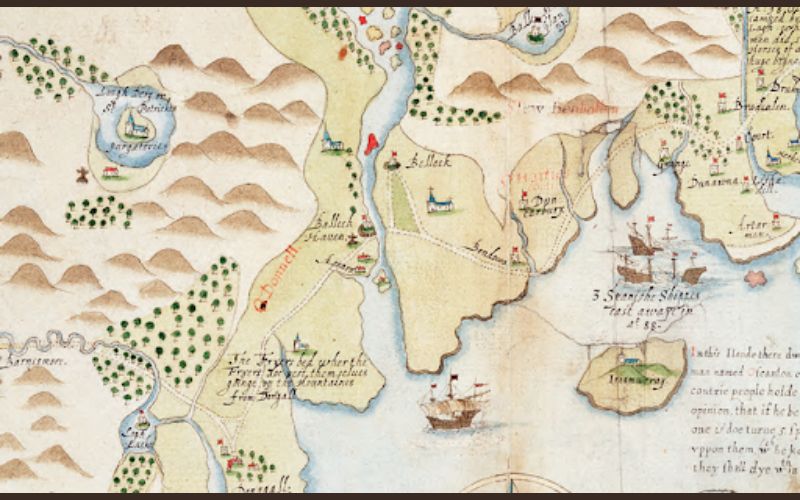

One of Ireland’s oldest historic maps, Captain John Baxter’s "A true description of the Norwest partes of Irelande" (circa 1599), holds the untold story of Elizabethan espionage and the sly art of spy-craft during the Tudor conquest of Ireland.

Concealed behind the map’s bound sheet, undisplayed in the National Maritime Museum in London, lies the relatively unknown history of the English soldier-spy, Captain John Baxter.

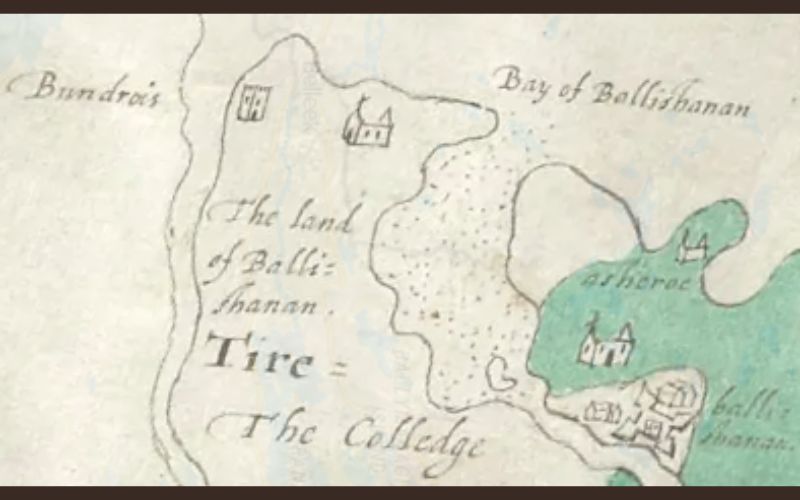

However, a high-resolution part of Baxter’s map features in the recently published Ballyshannon Historic Towns Atlas by the Royal Irish Academy, authored by Donegal historian Angela Byrne, and a copy of the full map can be viewed in the Facebook group 'Where, Erne, Drowes and Duff meet the sea.'

A part of Baxter's map.

Colourfully produced by Battista Boazio, Baxter’s map depicts his undercover observations of the unconquered Gaelic landscape of the north-west in the warring years before the Battle of Kinsale (1601), the Flight of the Earls (1607) and the Ulster Plantation (1609).

As recorded in the State Papers relating to Ireland during Elizabeth’s reign, Baxter was employed by Her Majesty’s Service during the Nine Years’ War (1593-1603). He covertly operated as a soldier-spy in “all services by sea and land” under the English military command of Sir Richard Bingham and Sir Conyers Clifford.

Elizabethan espionage was overseen by Lord Burghley, William Cecil, Queen Elizabeth’s chief adviser. Baxter first operated as a soldier-spy during Sir Richard Bingham’s time in Ireland in 1579. Both Bingham and Baxter reported to Elizabeth’s spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham. Following Walsingham’s death in 1590, his spy-craft protégé, Burghley’s son, Robert Cecil, was chosen as Elizabeth’s new spymaster.

The Burghleys oversaw a sophisticated spy network in Ireland. This spy network can be historically imagined as a spider web – spun to entrap targeted prey with its silk anchor threads always attached to the Burghleys. With one spin of the thread, Bingham mapped western Ireland, and with another spin, the soldier-spy, Baxter.

After working for Bingham, Baxter was sent to Sligo by Burghley to work under Conyers in 1597. After only four days, he coerced the O'Connors and McSwynes to join with Conyers and convinced them to never join with the powerful Gaelic leader, Red Hugh O'Donnell, Lord of Tyrconnell.

After this initial, strategic success of divide and conquer, Baxter then focused on one of his main spy operations in Sligo – gathering intelligence from the borders to create a map of the north-west, specifically of O’Donnell’s country.

Two years into Baxter’s intelligence gathering and mapping of Sligo, Conyers was killed and beheaded at the Battle of Curlew Pass (1599) by the joint forces of O’Donnell and O’Rourke. A day later, Baxter and company met O'Donnell on “the island where the English shipping lay” off the Sligo coast.

While drinking wine, O'Donnell boldly showed them the bloody head of Conyers, leading to O'Connor yielding to O'Donnell. Baxter gave assurances for O'Connor's “safe going and coming," implying that Baxter slyly acted as a trusted middleman between O'Donnell and O'Connor. If O'Donnell knew Baxter's clandestine motives, Baxter would have been beheaded, and O'Donnell would have enjoyed drinking Baxter's blood-red wine.

After Burghley’s death in 1598, his spymaster son, Robert Cecil, then sent his solider-spy on a secret mission to infiltrate and map O’Donnell’s country. Baxter travelled to the Sligo-Leitrim border by Bunduff and then crossed into O’Donnell’s stronghold of Tirhugh by Bundrowes Castle, today’s Magheracar townland in Bundoran.

The history of the north-west passed through this vitally significant borderland, historically known as the Moy (Magh Ene). Bundoran historian, Father Paddy Gallagher stated in his book, "Where Erne and Drowes meet the sea" (1961), that the Moy was “A main street of history, where the cavalcade of the centuries sweeps by its rocky shores in cattle-raid, hosting, and battle-charge” – Baxter stealthily swept by, too.

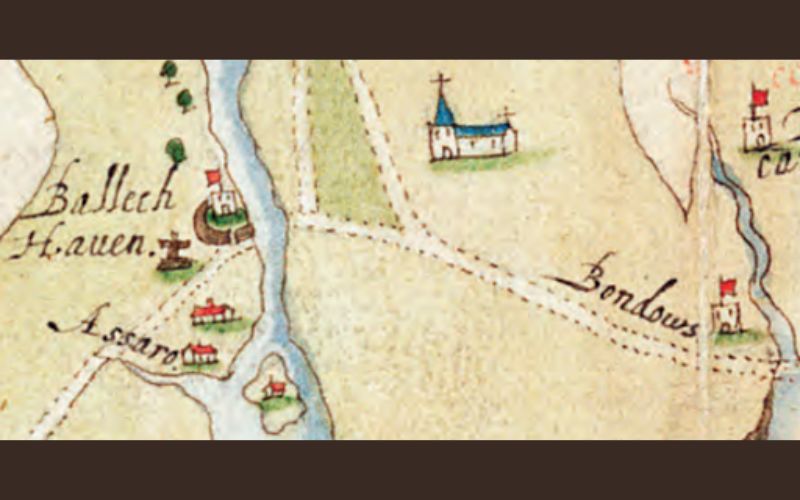

Three strategically important buildings in the north-west that Baxter observed were the fortified Gaelic chieftains’ castles and the churches and abbeys. The castles are highlighted on Baxter’s map with red tower flags, and the churches and abbeys with blue steeple roofs.

From L-R: Assaroe, Ballyshannon Castle, Finner Church, & Bundrowes Castle (Magheracar, Bundoran)

Baxter may have encountered resistance by coastal Gaelic clans in the Bundoran area, resulting in an inaccurate observation of the eastern rather than western location of Finner Church on this part of the map.

The historical records from the Plantation Jurors of 1603 report that Finner was one of the two churches in Magh Ene. The other church was located in Ballyhanny, south of Ballyshannon, which is not shown on the map. The location of Finner Church is accurately observed on the western side of the coastal routeway on the ‘six escheated counties of Ulster’ map (1610) that also features in the Ballyshannon Atlas.

Baxter would later return to Ballyshannon with Sir Henry Dowcra, who he served with under Bingham in Connacht in the 1580s. Dowcra’s forces seized Assaroe in December 1601 and O’Donnell’s Ballyshannon Castle in March 1602.

Overall, Baxter’s cartographic observations of the castles, churches and abbeys of strategic interest to Cecil and the English were mostly accurate.

From L-R: Bundrowes Castle (Magheracar, Bundoran), Finner Church, Ballyshannon Castle & Assaroe.

In O’Donnell’s country, Baxter “conferred with two or three Spaniards, who had been there ever since the Spanish fleet was cast away." Three Spanish Armada shipwrecks are noted on the map off the Sligo coast by Inishmurray. He also obtained from the Spaniards the name of O’Donnell’s messenger to Spain, Hugh Duff O’Deavan.

In Ballyshannon, Baxter observed that “two Scottish barks came in with provisions” for O’Donnell. He proposed to his spymaster, Cecil, that English galleys were needed and “if employed by Her Majesty, would do much good in the north”. He also held private conferences with those seeking to betray O’Donnell. Baxter was evidently hell-bent on dividing and conquering the native Gaelic clans.

Baxter’s shrewd observations informed the English army during the Nine Years’ War and were also sent back to Cecil, who spun the next thread – instructing Boazio to finish the map.

Years later, in the reign of James I, Baxter was granted the O’Connor’s land in Sligo. He cunningly reflected on his spy-craft, claiming that “I did use myself so well among them in those days” that “I have been suffered to travel among them, where never an Englishman but myself would be”.

Although Boazio finished this aesthetically beautiful map based on Baxter's imperial observations, the map at first glance is deceiving, as it appears to portray the Gaelic calm before the colonial chaos of the plantation storm.

The vividly drawn and coloured green woods and gold mountains of the north-west of Ireland suggest that calm. However, in reality, Baxter’s map insidiously forecasted the storm.

Baxter's map of Elizabethan espionage represents a historic last and first for Gaelic Ireland. It is the last map that depicts the unconquered Gaelic landscape during the Nine Years’ War, but for the English spy’s Irish eye – he also tragically crafted the first map of the Tudor conquest of Ireland.

*Éamon Ó Caoineachán (Eddie Keenaghan) is a poet, writer and historian, originally from Bundoran, Co Donegal, and currently living on the Gulf Coast of Texas. He is a PhD postgraduate in Arts at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick.

Comments