In 1965 a well-intentioned change to the U.S. Immigration system called the Immigration and Nationality Act had the unintended effect of closing the golden door to generations of would-be Irish immigrants.

Its shadow still falls over us five decades later. In his new book Unintended Consequences, author Ray O'Hanlon examines how and why and asks what can the Irish do next?

The penny hasn't dropped in Dublin or Washington D.C. yet, but we may soon be on the cusp of a third big wave of Irish immigration.

With vulture funds and homemade property developers pricing out young first-time house buyers from Dublin to Galway and no relief in sight, the stage is being set for another grand Irish exodus and as usual, the ministers in charge will be the last to know.

Back in 1998, he wrote an award-winning book about the then fraught state of Irish immigration to the U.S. called The New Irish Americans which had some relevant warnings for the Irish on both sides of the Atlantic.

The idea for the book arose out of the deepening plight he was witnessing and recording, namely that it had become almost impossible to make the journey that previous generations had and start a new life here in the land of opportunity. What, O'Hanlon wondered at the time, will happen if the pool of Irish immigrants is not replenished?

“That book was a culmination of a decade of reporting on the immigration issue as it pertained to the Irish and the undocumented Irish, and those who had secured legal status with the various visas pushes here. It dealt with a number of issues, politics and culture and immigration.”

It's time we reflected on the whole picture, the better to find the path forward, the new book suggests. What O'Hanlon realized is that every few generations of the Irish have a big fight on their hands to tackle the immigration question. For example, a group called the American Irish Immigration Committee (AIIC) who formed in the late 1960s were the first to understand the long-term consequences of the 1965 Act.

“I was only sort of vaguely aware of the AINIC,” O'Hanlon continues. “I could see references to it in old Irish Echo archival pieces on microfilm, so I knew of it only in the vaguest and most limited way. But then as I familiarized myself with the work of the reform committee once led by Judge John Collins and Father Donald O’Callaghan, I realized there was an Irish Immigration Reform Movement (IIRM) and an Irish Lobby for Immigration Reform (ILIR) long before us. They went into battle in Washington, appearing before committees arguing that Ireland had been sidelined and ill-treated by the 1965 act.”

Going back to the source of the problem and then opening out from there to ask how it had happened and why the Irish can feel especially hard done by it, is part of the journey of O'Hanlon's comprehensive and illuminating new book.

“I think the 1965 Act was conceived and passed and signed into law in the spirit of the time, in the time of the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act and I think it was well meant.”

Talk about unintended consequences, though. At the time Ted Kennedy was offering to slip in a little set aside for the Irish but the government in Dublin, with lamentable lack of foresight, said no thanks. O'Hanlon's book records how all the leading political figures of the day were saying that it wasn't going to change things, that the face of immigration wasn't going to change, they were simply placing a new emphasis on family reunification, but that's not the way it worked out.

The change was felt more immediately over here because it could literally be seen, and after the surprise turned to shock it led to the formation of AIIC and a battle for some sort of clawback of the effects of the 1965 Act.

Different generations of Irish immigration activism achieved different results too. “At the end of the IIRM campaign, you could report a significant measure of success. Between the jigs and the reels over 70,000 secured green cards. That was no mean achievement in the context of the time. And then 9/11 happened and it would take sort of a deep psychological study or political scientist, to examine what changed in America in the aftermath. Attitudes began to change towards immigrants. We saw it during the Trump years, the idea of immigration and immigrants became a negative, becoming some sort of threat, of what existed beyond America's borders.”

Later the ILIR came on the scene with demonstrations in Washington and new kinds of activism on the internet and social media. “It was really a very obvious and forceful presence so I'm sure the failure to get reform in the House in 2013 was incredibly discouraging.”

After that the reform push “fell into a trough,” O'Hanlon says. “And then we had Trump. But during its time, ILIR threw a very strong light on an issue that is not just years old, but decades old. And here we are, still talking about it.”

“Never underestimate the power of sentiment. The ones that link Ireland and America and the Irish and Irish Americans. You overlook them at your peril. It's not just politics, it's not just visa numbers, it's far, far deeper than that.”

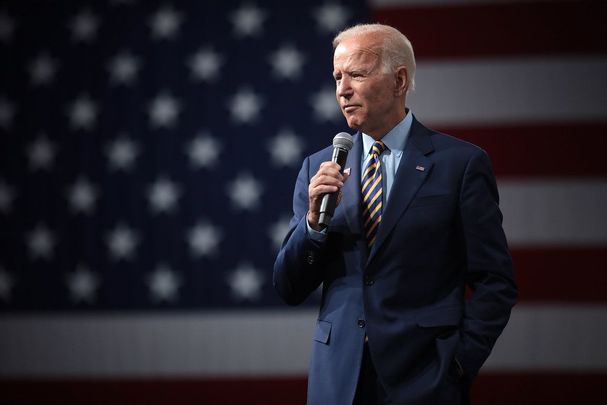

Now the Biden presidency offers a new hope. “If you talk about the power of sentiment, my God, he's wearing it on his sleeve. He has a sense of past, and his past is, compared to JFK who was the money version, is much more sort of down-to-earth, real-life, struggle, blue collar working-class family. He gets it.”

If Biden goes to Ireland soon it'll be very interesting, O'Hanlon predicts. “June would be a logical time to build in a stump over in Ireland. And perhaps a reminder that there is an unresolved issue regarding the Irish within the broader context of eleven million undocumented.”

So the great work is ongoing, O'Hanlon concludes. “Who writes a third book on this? It won't be me. Hopefully somebody steps up ten years from now if there's a need because God forbid we're still stuck in this sort of situation, with so many living in the shadows. I hope it's resolved by then. I mean, we have Biden now.”

Comments