What would Roy Cohn do? President Donald Trump may well be asking himself that very question. Or maybe he asked already and got this answer: declare war!

That, in the long run, may be bad news for Trump.

Last week, the Republican Party’s simmering civil war exploded. “The Freedom Caucus will hurt the entire Republican agenda if they don't get on the team, & fast. We must fight them, & Dems, in 2018,” Trump tweeted this week.

Trump is fuming that the ultra-conservative Freedom Caucus helped sink the president’s proposal to replace Obamacare. Trump has little use for the hard-line ideological warriors who make up the Freedom Caucus. And those anti-spending fanatics feel the same about Trump who, by their standards, is little more than a big spender.

This all comes as a new book reminds us that this isn’t the first time the Republican Party has nearly imploded. A central figure in this previous Republican civil war was one of the most infamous Irish Catholics in American history. Another, ironically, was one of Trump’s closest friends, Roy Cohn, a ruthless, secretive power broker.

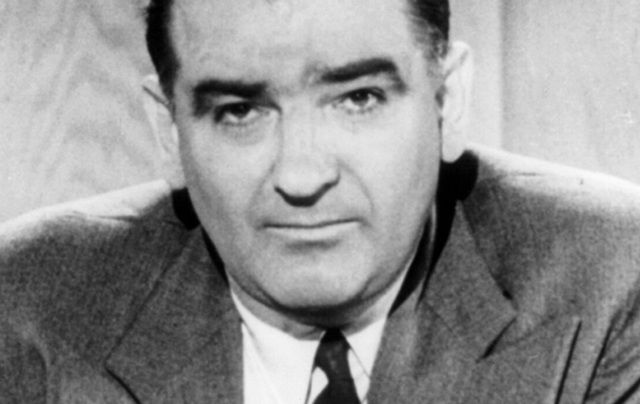

The book is Ike and McCarthy: Dwight Eisenhower’s Secret Campaign Against Joseph McCarthy. In it, author David A. Nichols chronicles the rise of Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, who rode a wave of anti-Communism to dizzying heights of power, only to come crashing down.

The 1950s were an interesting time for Irish Catholics. World War II had served immigrants and their children well, helping them to assimilate.

But Catholics remained a mysterious tribe. The fact that they dominated most major American cities, from the police precinct to City Hall, still unnerved some in the American heartland. Journalist Paul Blanshard actually churned out a string of best-selling books in the 1950s (American Freedom and Catholic Power, The Irish and Catholic Power, My Catholic Critics) outlining the dangers of papist power in America.

This highlights one reason McCarthy was such a powerful figure. His mother was an immigrant from Tipperary while his father was Irish American, but the McCarthy family settled not in New York, Boston or Chicago.

The senator came from a farm in Wisconsin. He did not have the stereotypical background of a big-city “ethnic” politician.

Then there was the second issue urban Catholics and rural Protestants could agree on: Communism. The fight against Communism was a golden opportunity for Irish Catholics to prove just how loyal they could be as Americans. It just so happens that the very church which scared Protestants was also the most fiercely anti-Communist institution on the planet.

McCarthy, along with his chief counsel Cohn, was able to exploit fears of Communism and become one of the most powerful political figures of the 1950s, challenging the more moderate approach favored by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

This set up a nasty war within the Republican Party, in which McCarthy and Cohn decided to fight as brash warriors, gleefully engaging in what came to be termed “witch hunts.”

Sound familiar?

That, of course, is how Trump fights, and no wonder. Trump idolized Cohn. They were close pals until Cohn died of AIDS in 1986.

Cohn “ushered [Trump] across the river and into Manhattan, introducing him to the social and political elite while ferociously defending him against a growing list of enemies,” The New York Times noted last year.

“Decades later, Mr. Cohn’s influence on Mr. Trump is unmistakable ... the gleeful smearing of his opponents, the embracing of bluster as brand, has been a Roy Cohn number on a grand scale.”

All of which makes it absurd to hear Trump blast the congressional “witch hunt” over Russia. It was McCarthy and Cohn -- and later Trump -- who mastered these tactics.

More importantly, as Nichols’ book makes clear, Eisenhower was able to win the Republican civil war because he was able to fight McCarthy carefully and tactfully.

That does not sound like something Roy Cohn taught Donald Trump.

Comments