On May 5, 1981, Bobby Sands died at HM Maze Prison in Northern Ireland. He was 27 years old.

Sands was born on March 9, 1954, in Rathcoole in North Belfast, a majority loyalist area. His family had succeeded in living reasonably peacefully in the area by keeping their own religion under wraps. When word spread of the Catholic Sands family, however, intimidation and threats began, forcing the family to move when Sands was just ten years old.

Intimidation followed Sands throughout his life and, at 18, he was forced out of his apprenticeship as a bus builder because of threats.

Once again, the family was threatened out of their home in 1972 and after 18 months of pressure, they relocated to the newly built Twinbrook estate on the fringe of nationalist West Belfast.

At 18 years of age, Sands joined the Republican movement, writing, “My life now centered around sleepless nights and standbys dodging the Brits and calming nerves to go out on operations. But the people stood by us. The people not only opened the doors of their homes to lend us a hand but they opened their hearts to us. I learned that without the people we could not survive and I knew that I owed them everything.”

In October 1972, he was arrested for the first time for the possession of four handguns and spent the next three years in Long Kesh prison where he was regarded as a political prisoner. During this time, Sands used his imprisonment to learn Irish and read widely.

Bobby Sands in Long Kesh, 1973. (Fair Use / Bobby Sands Trust)

On his release in 1976, Sands returned to his original role with his local IRA unit as well as working to tackle the social issues that faced the Twinbrook area as a community activist.

Within six months, Sands had been arrested again. Captured by the RUC following a bomb attack and a gun battle, Sands and six others were taken to Castlereagh Detention Centre and brutally interrogated, but Sands refused to give any information other than his name and address. He was held on remand for 11 months. When his case finally came to trial in September 1977 he refused to recognize the court, as he had previously done when first arrested.

Although unable to prove Sands’ involvement in the bomb attack, he and the other three passengers in the car at the time of his arrest were each sentenced to 14 years in prison for the presence of a handgun involved in the gun battle in the car.

By this time, the “political prisoner” status of those charged with acts of terrorism had been removed, sparking five years of protest by convicted paramilitary prisoners. The withdrawal of “Special Category Status” meant that these prisoners were no longer treated similarly to prisoners of war – they now had to wear prison uniforms and carry out prison work.

The withdrawal of this special status was part of a policy undertaken by the British government to criminalize such prisoners.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

The protest against the withdrawal of the “Special Category Status” began with a blanket protest in 1976 in which prisoners refused to wear prison uniforms. This was followed in 1978 by a dirty protest after a number of attacks on prisoners leaving their cells to "slop out" (i.e., empty their chamber pots). Prisoners refused to wash and covered the walls of their cells with excrement.

The first hunger strike began in October 1980. Seven men - IRA members Brendan Hughes, Tommy McKearney, Raymond McCartney, Tom McFeely, Sean McKenna, Leo Green, and INLA member John Nixon - were selected to take part. The number seven was chosen as it matched the number of signatories on the 1916 Irish Proclamation of Independence. On the apparent concession of the British Government to their Five Demands, the hunger strike ended after 53 days on December 18, 1980.

The Five Demands outlined were:

- the right not to wear a prison uniform;

- the right not to do prison work;

- the right of free association with other prisoners, and to organize educational and recreational pursuits;

- the right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week;

- full restoration of remission lost through the protest.

When it became apparent that the British Government had no intention of upholding its commitment to meeting these demands, a second hunger protest began.

Sands was an influential figure within the Maze by this time, having previously been elected as the IRA’s commanding officer within the prison. He was the leader when the second hunger strike began on March 1, 1981. On that day, Danny Morrison issued a statement on behalf of the "republican POWs in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh:"

"We have asserted that we are political prisoners and everything about our country, our arrests, interrogations, trials, and prison conditions, show that we are politically motivated and not motivated by selfish reasons or for selfish ends. As further demonstration of our selflessness and the justness of our cause a number of our comrades, beginning today with Bobby Sands, will hunger-strike to the death unless the British government abandons its criminalization policy and meets our demand for political status."

Unlike the first strike, prisoners joined at staggered intervals hoping to gain more public attention and support.

Just five days after Sands began his hunger strike, the independent Republican MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, Frank Maguire, died, which resulted in a by-election for the constituency. Sands stood as the Anti-H Block candidate. He won the election beating the Ulster Unionist Party candidate Harry West to gain a seat in the British House of Commons.

The desired attention was finally drawn towards H-block. Despite hopes of a compromise, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was unwilling to negotiate.

"We are not prepared to consider special category status for certain groups of people serving sentences for crime,” Thatcher said during the 1981 hunger strike. “Crime is crime is crime, it is not political."

Margaret Thatcher (Getty Images)

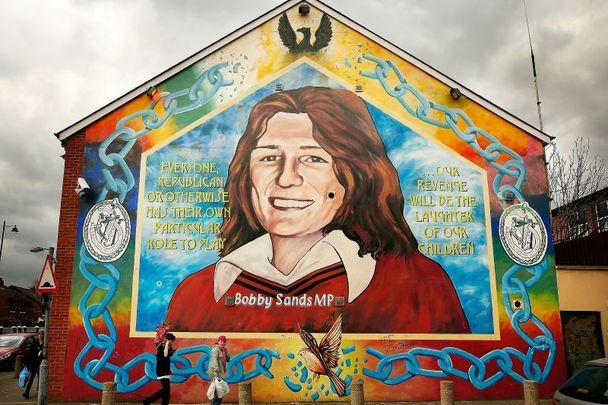

After 66 days on hunger strike, Bobby Sands died on May 5, 1981. Three further strikers were to die in the next two weeks: Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, and Patsy O’Hara. Thatcher still refused to negotiate.

The further deaths of Joe McDonnell and Martin Hurson caused concern amongst the hunger strikers' families and ratcheted up the pressure to find a way to end the strike.

The strike began to falter on July 31 when the mother of Paddy Quinn requested medical intervention to save her son's life. More deaths followed: Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee, and Michael Devine.

As more families announced their intent to allow medical intervention to save their sons, the strike was officially called off on October 3 but not before a total of ten hunger strikers lost their lives.

Despite the apparent initial failure of the hunger strike, the hunger strike's main figures, especially Sands, became heroes among the Republican movement and led to further support for Sinn Féin as a mainstream political party.

Although Thatcher seemed to have defeated the strike, she became a figure of Republican hatred and IRA recruitment was boosted by the heroic nationalism of the strike’s martyrs. Sands’ election, in particular, was seen as a massive propaganda victory for the movement.

* Originally published in May 2017, updated in May 2024.

Comments