One author claims that President John F. Kennedy's Secret Service agents were both hungover and sleep-deprived on the day of his assassination.

When Kennedy was first shot, at 12.30 pm on November 22, 1963, the bullet went through his neck but did not kill him. It was another shot, five seconds later, that damaged his brain and skull and killed him.

Between that first shot and the fatal blow were five seconds in which the president’s life might have been saved had his Secret Service agents not failed to take evasive action, suggests Vanity Fair, in an article adapted from Susan Cheever’s book "Drinking in America: Our Secret History.”

The article describes how JFK’s Secret Service agents responded during the shooting: “Roy Kellerman, the leader of the security detail, did not seem to know what was happening. He thought a firecracker had gone off. "

"William Greer, (an Irish-born immigrant from Tyrone) at the wheel of the president’s car, did not immediately speed up or swerve away from the shots."

"Paul Landis, in the vehicle trailing Kennedy’s, did not jump forward to protect the president with his body; neither did Jack Ready."

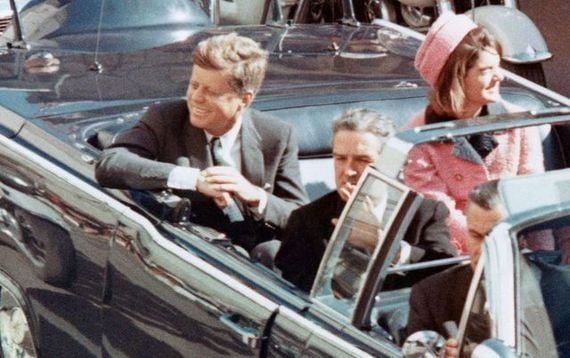

JFK's Dallas motorcade

"Clint Hill, riding a few feet behind and to the president’s left, was part of the first lady’s detail. After the fatal shot was fired, he leapt onto the rear of the presidential limousine and kept her from jumping off the back.”

As agent John Norris said in Bill Sloan’s book "J.F.K.: Breaking the Silence" and in an interview for Vincent Michael Palamara’s book "Survivor’s Guilt": “Except for George Hickey and Clint Hill, [many of the others] just basically sat there with their thumbs up their butts while the president was gunned down in front of them.”

According to the Vanity Fair report, nine of the 28 Secret Service men who were in Dallas with Kennedy that day had been out until the early hours of the morning. A few were sleep-deprived and had been drinking while traveling with the president.

However, this type of partying by Secret Service members was not unusual.

In his 2008 book, "The Echo from Dealey Plaza," Abraham Bolden, one of the only African American agents in Kennedy’s detail, writes that he was later framed and sent to prison as retaliation for speaking out about the lax behavior tolerated within the department.

The day of the assassination, Bolden says, he was standing in the Secret Service office in Chicago, just after the president was shot, when he heard a fellow agent say, “I knew it would happen. I told those playboys that someone was going to get the president killed if they kept acting like they did. Now it’s happened.”

Bolden told Vanity Fair: “The biggest problem I ran into with the Secret Service when I was an agent was their constant drinking.

“When we would get to a place one of the first things they would do was stock up with liquor. They would drink and then we would go to work.”

On November 22, Bolden says the Secret Service agents' "reflexes were definitely affected by, number one, the loss of sleep and, number two, the fact that [some may have] consumed that amount of alcohol.”

Being sleep-deprived while on duty was not uncommon among Secret Service members during JFK’s years in office.

In his book "The Kennedy Detail," agent Gerald Blaine recalled how he struggled to stay awake on numerous occasions: “Working double shifts had become so common since Kennedy became president that it was now almost routine. The three eight-hour shift rotation operated normally when the president was in the White House, but when he was traveling . . . there simply weren’t enough bodies.”

The agents also rarely had time to eat. Blaine says he typically kept a few bags of peanuts in his flight bag and the peanuts would often be the only thing he ate all day.

Journalist Seymour M. Hersh wrote in his book "The Dark Side of Camelot" that agents acknowledged that the Secret Service’s socializing intensified each year of the Kennedy administration, to a point where, by late 1963, a few members of the presidential detail were regularly remaining in bars until the early morning hours.

As JFK began his campaign for a second term, he traveled incessantly.

“Motorcades were the Secret Service’s nemeses,” said agent Gerald Blaine. “There were an endless number of variables ... and you could never predict how a crowd would react.”

At the start of Kennedy’s administration, his agents would typically hitch alongside the presidential vehicle on retractable running boards affixed to the car. However, this would block the president’s constituents from approaching him for a handshake or from having a direct line of sight to him.

On the day of Kennedy’s assassination, the running boards of his car had been retracted and were, therefore, unable to accommodate his agents. Although some in Kennedy’s security force have subtly suggested the president brought trouble on himself through his aversion to the running boards, others have refused to blame him.

Agent Gerald Behn, the head of the White House detail, who was not in Dallas that day, said: “I don’t remember Kennedy ever saying that he didn’t want anybody on the back of his car.”

On the night of November 21, after the president and the first lady had retired to their suite, the Secret Service agents headed out of the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth in search of food around midnight.

VF writes: “Word got out that there was a buffet with food a few blocks from the hotel. In fact, local journalists had kept the Fort Worth Press Club open so that visiting White House reporters could go and grab a bite. And just after midnight, nine of the 28 agents in the presidential detail walked over, in search of food. There was none. Even so, the agents stayed around for Scotch and Sodas, cigarettes, and a few cans of beer. Two of the agents then headed back to their rooms; seven continued on.”

CBS newsman Bob Schieffer, at the time a young night police reporter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, recalled: “I went to the club when I got off at two a.m.”

Nearby was the Cellar Coffee House, a legendary hangout: “The Cellar was an all-night San Francisco–style coffee house down the street and some of the visiting reporters had heard about it and wanted to see it. So we all went over there and some of the agents came along. The place didn’t have a liquor license, but they did serve liquor to friends—usually grain alcohol and Kool-Aid.”

According to letters submitted to the Warren Commission, six of the Secret Service members stayed at the Cellar until about three in the morning. Paul Landis, who would ride in the car behind the presidential limousine, wrote that he didn’t leave until five a.m.

Agent Clint Hill told Vanity Fair that he left the Cellar before two a.m., went back to the hotel, and put in his breakfast order for six a.m. (He told the Warren Commission that he had stayed until 2:45.)

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

“Every one of the agents involved had been assigned protective duties that began no later than eight a.m. on November 22, 1963,” said Philip Melanson, an expert on politically-motivated violence, who would help oversee the archive of the Robert F. Kennedy assassination.

Twelve agents were specifically responsible for guarding President Kennedy and the first lady in the motorcade on November 22.

Vanity Fair describes the set-up that morning: “In the lead car, directly in front of Kennedy’s, sat Agent Winston Lawson, along with Jesse Curry, the Dallas police chief. Behind the lead car, Secret Service agents William Greer and Roy Kellerman were in the driver and passenger seat of the president’s limousine, a 1961 midnight-blue four-door Lincoln (codenamed the “X-100”), which had been modified and reinforced for presidential use by the Ford motor company. "

"This second car carried the Kennedys (codenamed “Lancer” and “Lace”) and the Connallys. Four retractable side steps and two steps with handles on the rear of the car had been added to allow security personnel to jump on or off, or be carried along. Modifications had widened its wheelbase and increased the car’s weight from 5,200 pounds to almost 7,800 pounds. Even for an experienced driver, it was a difficult vehicle to maneuver, especially on a route like the one in Dallas, which included some sharp right-angle turns."

“The third car, also configured with protruding side steps, was a 1955 black Cadillac convertible (codenamed “Halfback”), driven by Secret Service agent Sam Kinney. It was Kinney’s job to stay a few feet behind the presidential limousine at all times: close enough so that the two cars couldn’t be separated by someone lunging between them, but not so close as to cause a collision. Paul Landis, Jack Ready, and Clint Hill rode the running boards along the sides of this follow-up car. Inside, sat agents George Hickey, Emory Roberts, and Glen Bennett.

“Agent Hill—poised just a few feet behind the Kennedys, who sat in the back seat of the car in front of him—was nervous, according to accounts he has written about the events in Dallas in his books. The motorcade kept speeding up and slowing down, speeding up and slowing down. That morning, he frequently jumped off the running board to jog alongside the vehicle. Kinney, right behind him in Halfback’s driver’s seat, watched him struggle to keep pace with the cars.”

Hill recalled what happened after the first shot: “I described it as an explosive device. It resembled a firecracker, but a loud one, and it came over my right shoulder from the rear. I wasn’t absolutely sure what it was. I turned toward the noise.”

It took six seconds for him to reach the presidential limousine. Footage of the assassination shows that Hill was the only Secret Service agent within reach of the car to have moved toward the back of the limo. He climbed onto the president’s vehicle and pushed Jackie Kennedy—who had crawled up onto the trunk—back into her seat. It was too late to save the president.

Agent Jack Ready was also on the footboards, yards from the president. Behind him, in similar proximity, was Paul Landis, also from the first lady’s detail.

“I knew right away it was a gunshot,” said Landis. “I was a hunter. I’ve done a lot of shooting. There was no doubt in my mind, in fact.”

But although Landis noticed Kennedy “leaning to the left,” he said in the blur of the moment, he did not connect the sound of the gun and the president’s movements.

Landis, Hill, and Glen Bennett, who was inside their chase car, had all gone to the Press Club and then the Cellar the night before. According to the statements they made to the Warren Commission – Hill, Ready, and Bennett had stayed until around three a.m.; Landis, for two hours longer.

When asked what might have impeded their actions that day, Landis said that the question of “the drinking was blown out of proportion ... So other than that, I think you could say, ‘lack of sleep.’ But you’re wide awake . . . going on adrenalin.”

Did being out all night factor into their slow reaction time? “That’s a tough one,” he told VF. “I don’t think that affected me. That’s an arguable point.”

In contrast, the fourth car in the motorcade, housing Vice President Johnson and his wife, was guarded by other agents, including Rufus Youngblood. Youngblood had not joined the others the previous evening, and after the first shot, Youngblood, in line with his Secret Service training, pushed Johnson to the floor of the car and covered him with his own body.

Lyndon B. Johnson being sworn in aboard Air Force One (Getty)

A week after the assassination, President Lyndon Johnson ordered an official investigation of the events surrounding JFK’s death. The chairman of the investigation, Earl Warren the chief justice of the Supreme Court, was outraged to learn that a half dozen Secret Service agents had been out past midnight the night before the assassination.

Vanity Fair writes: “The revelation came not from depositions, but from a Drew Pearson radio report on November 30, 1963, followed up by his December 2 column in the Washington Post. Pearson, an establishment journalist well-known for speaking truth to power, was also a close friend of Warren’s.

“Pearson would later explain that his information about the Secret Service had come to him through Thayer Waldo, a Fort Worth Star-Telegram reporter who didn’t think his editors would dare publish a controversial story casting aspersions on the Secret Service. ‘Obviously, men who have been drinking until nearly three a.m. are in no condition to be trigger-alert or in the best physical shape to protect anyone,’ Pearson wrote. In fact, the head of the Secret Service, James Rowley, would later claim, in a report submitted to the Warren Commission, that he had known nothing about his staffers’ drinking until he read Pearson’s exposé.

“That column, now long forgotten, was a bombshell at the time, but one that never exploded. The Warren Commission duly questioned the Secret Service members about their activities the night before the assassination and found that, yes, some had been drinking. But in the 1960s the pastime of drinking heavily with peers or colleagues was considered acceptable behavior in many circles. Because of the lack of social stigma associated with overindulgence, it was hard for the panel’s members to know how to react.

"Senator Arlen Specter, who debriefed the agents for the Warren Commission, didn’t appear to consider their behavior a big deal. Indeed, the agents themselves were already devastated enough by the death of the president, whom most of them had revered. And although some of the men had broken the rules, many involved with the commission were eager to protect them from going down in history as the men who may have made mistakes on that fateful day.”

The 26 seconds of 8mm footage recorded by bystander Abraham Zapruder on his Bell & Howell movie camera that day shows that several of the Secret Service agents seemed momentarily suspended in place as the shots rang out.

"The men in Halfback were bewildered,” according to William Manchester, the author of "The Death of a President."

“They glanced around uncertainly. . . . Even more tragic was the perplexity of Roy Kellerman, the ranking agent in Dallas, and Bill Greer, who was under Kellerman’s supervision. Kellerman and Greer were in a position to take swift evasive action, and for five terrible seconds they were immobilized.”

H/T: Vanity Fair

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

*Originally published in November 2018. Updated in November 2022.

Comments