What would you do if you were hungry? Would you steal food? Would you steal money to buy food? Or would you fight for your perceived oppressor to get food? Such was the predicament of many young men in 1853 in Ireland.

Mark Green of Victoria Cross Online correctly points out, "During the 1840s, times became increasingly hard in rural Ireland with the outbreak of the Irish Potato Famine. It is believed that the hardship caused by the potato blight caused many Irishmen….to enlist in the army to escape."

It is worth looking at five brave men who fought in the Crimean War and received the Victoria Cross for their bravery. And there is no doubt about it: these men were brave. But it is also worth looking at the parts of Ireland from where they came to possibly give us a better understanding of why they enlisted.

First, let's look at what happened in Ireland before the Crimean War. The potato crop had failed successively due to blight from 1845 to 1852, leaving thousands starving, dead, or faced with coerced immigration. Queen Victoria visited Ireland for the first time in 1847, the worst year due to the highest recorded number of famine-related deaths, and a second time in 1853, trips that were more politically motivated than passion-filled for her starving Irish subjects. She visited two more times, in 1861 and 1900. Her two earlier trips hoped to increase her army and navy recruitment numbers.

In 1853, rumbles of war overseas resulted in an uptick in active recruitment for the British Navy and Army in Ireland. The Irish did not wake up on the morning of January 1, 1853, and declare The Great Hunger finished. Rural parts of Ireland would feel the pangs of that painful history for many years. The Crimean War began on October 5, 1853, with the Russian Empire on one side and Britain, France, the Ottoman Empire, and Sardinia on the other. Each country involved in the conflict had a specific interest —Britain's was to protect her trade routes to India and elsewhere. Enlistment numbers were down in England and Ireland, and war was brewing abroad with Russia. Money and clothing were promised if you signed up to fight. What would you do if you were cold and hungry?

Victoria Cross Medal via Photo: Mike Weston ABIPP/MOD, OGL v1.0OGL v1.0, via Wikimedia Commons

They have become known to some as the "Green Red Coats." Still, closer inspection of skirmishes, immigration numbers, bank depositor numbers in New York, and even population decline in areas where some of these enlisted young men grew up demonstrate that they donned the scarlet not for patriotic purposes but because they had ulterior motives. Some academics would posit the magnificent uniforms possibly drew young men to enlist to fight in the Crimean War for Britain. Yet, it is also feasible to entertain another more realistic and widespread notion —they were cold and hungry.

Take, for instance, the young men in Nenagh, North Tipperary, who fought from Monday, July 7 until Wednesday, July 9, 1856, because they were told to hand back their regimental trousers, tunics, and shakos to the British army and were then informed that they would not be paid the promised enlistment bounty. Some of these men had risked their lives in Crimea for an enlistment bounty of ten pounds. Instead, they had received "Virtually none of their promised enlistment bounty," says David Murphy, author of "The Battle of the Breeches": The Nenagh Mutiny, July 1856.

This mutiny was not an isolated incident. Similar skirmishes occurred in Cork and Clare in September of 1855. According to Murphy, "The penny-pinching attitude of the Government was caused directly by the end of the Crimean War and a desire to save money now that the militia was perceived to be no longer needed."

It is no wonder, really, that when faced with returning home, half-naked men who risked their lives for a promised, but never paid, ten pounds would mutiny.

Thomas Grady, County Galway

Thomas Grady. (Image via Victoria Cross Online Courtesy of Mark Green)

Let's return to the five brave Victoria Cross recipients who fought in the Crimean War. The first VC Medal recipient we shall discuss is a man from my own County, Galway. Thomas Grady was born in Claddagh in 1835, which is also the birthplace of the Claddagh Ring. Grady enlisted underage in 1853 in the 99th Foot (2nd Battalion Wiltshire Regiment) in Liverpool and transferred on February 13th, 1854, to the 4th King's Own. Grady received two Victoria Cross recommendations for acts of bravery on October 18th and November 22nd, 1854. Because he'd already been recommended for one act of bravery in October, he received the medal and not the bar.

"The award to Grady of a VC and Bar would have been more appropriate, but the original VC warrant did not permit the award of a Bar for a second act of gallantry if the act occurred before the approval and presentation of the original VC," says Mark Green.

Grady's bravery resulted in a poem in his honor, How Tom Grady Cleared the Gun. "Cold, hunger, fever, wounds, and death had thinned that gallant band; Yet once again, 'mid frost and snow, those gunners take their stand," demonstrates that despite severe living conditions, Grady persevered and was decorated by Queen Victoria at the first VC presentation in Hyde Park, London on June 26th 1857.

By the time Grady enlisted, he would have been almost 18. The Great Hunger was still in his recent memory. According to The Great Irish Famine Online, the population of Galway grew by 2,780 people between 1841 and 1851, but surrounding towns saw their populations fall by an average of 100-300.

In 1845, Claddagh was a separate town from Galway with distinct traditions. In 1820, James Hardiman, a librarian at Queen's College Galway (NUI Galway), said the people in the coastal fishing village of Claddagh "rarely speak English, and even their native language, the Irish, they pronounce in a harsh, discordant tone, sometimes scarcely intelligible to the town's-people." The fact that the Claddagh was a fishing village may have spared its inhabitants the hunger created by the potato blight between 1845 and 1852. Grady, of course, stood out in the British army because of these distinctive roots. In 1859, British writer John Leech remarked of the people living in the Claddagh, "They call every man who does not belong to their community a stranger; even a man from the next parish is a stranger; and it their rule not to intermarry with strangers."

Galway was one of the most populous counties during the years leading up to the Famine. Professor Tyler Anbinder's Beyond Rags to Riches project shows that as many as 6,000 Irish men and women from civil parishes surrounding Galway Bay opened accounts with the Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank between 1850 and 1858. Anbinder states that this represents only a 5% sample of New York's Irish community, suggesting that the actual immigration numbers would be far higher.

This brings us back to our Victoria Cross medal recipient, Thomas Grady, who did not return to Claddagh; he also emigrated. Grady died on May 18th, 1891, near Melbourne, Australia. He is highly respected for his two acts of bravery in the Crimean War.

William Coffey, County Limerick

William Coffey's grave. (Image via Victoria Cross Online Courtesy of Mark Green)

The second VC Medal recipient is William Coffey, born in the parish of Knocklong, County Limerick, in 1829. Coffey, a farm laborer, would have witnessed scenes of the potato famine in Ireland. He enlisted in the 82nd Regiment of Foot, The Prince of Wales Volunteers, in Fermoy in County Cork on November 24th, 1846, at 17 years and 10 months old. He was 5 foot five inches tall.

In March 1855, Coffey was part of the Siege of Sebastopol in Crimea. As a side note, all VC Medals are allegedly made with bronze from Russian guns retrieved from that now-famous battle. Coffey saved the lives of 12 men by picking up a live shell that landed among them and threw it over the parapet on March 29th, 1855. That was just one heroic act performed by Coffey. Numerous others landed him a promotion to Corporal in March and Sergeant in November 1856, in addition to the French Medaille Militaire awards, the Turkish medal, and the Crimean Medal for the Crimean Campaign.

On February 24th, 1857, Coffey was one of the first awards of the new Victoria Cross announced in the London Gazette. Coffey and 61 men lined up before Queen Victoria in Hyde Park on June 26th, 1857, to receive his VC. According to Mark Green, "The Queen remarked in her diary, 'I was glad….to give the Victoria Cross…to Corporal Coffey of the 34th, whom I had seen at Aldershot.'" Amazingly, despite his outstanding achievements and press coverage, we do not have a photo of William Coffey. His life was filled with sadness, having lost all of his children to sickness and his first wife at the age of 28. Coffey did remarry, and again, a child died due to illness.

What was Knocklong, County Tipperary like during the years of the Famine? Although the Beyond Rags to Riches site has no figures for the town, we can use its closest neighboring town for comparison. That town is Ballyspellane in the civil parish of Ballyscadden. In 1841, it had a population of 156. In 1851, it wasn't even on the map. According to University College Galway's website, Landed Estates Ireland's Landed Estates and Historic Houses 1700-1914, "The estate of John Vincent, trustee of the will of Westby Percival, at Ballyspellane North, Barony of Lower Ormond, was advertised for sale in January 1863. Ballyspellane North was in the possession of Margaret Perswell [Percival] at the time of Griffith's Valuation."

Anbinder's Beyond Rags to Riches shows four depositors from Knocklong with just under 150 depositors from nearby civil parishes. Again, using Anbinder's estimate of depositors representing just 5% of the number of Irish immigrants in New York alone from 1850 to 1858, the number of immigrants from Knocklong and its environs would be far higher. Given that the area of Ballyspellane was advertised for sale in 1863, we can conjecture that times were tough for a young William Coffey. He, too, did not return to his homeland after service and died an emigrant abroad. Coffey was plagued with ill health and died of Dysentery at the age of 46 on July 13th, 1875. He is buried in the Roman Catholic Section of the Spital Cemetery, Chesterfield.

John Connors, County Kerry

John Connors. (Image via Victoria Cross Online Courtesy Mark Green)

The third VC recipient is John Connors from Daugh, Listowel, in County Kerry. Connors was born in 1830, and as an aside, I love his pose in this picture. He enlisted in 1854 in the 3rd Regiment of Foot, later known as The Buffs, East Kent Regiment. Connors, according to Mark Green, received his VC award for the following brave act during the Crimean War: "On September 8th, 1855, in the assault on the Redan, Connors was in the thick of the action, when he saw an officer of the 30th Regiment of Foot who was surrounded by a group of Russians. Connors charged across to the officer, and shot one of the Russians, and bayoneted another, and saved the officer's life." Connors was awarded the VC posthumously, as he died in Corfu, falling from the battlements at Port Neuf, on January 29th, 1857.

In 1841, Daugh, near Listowel in County Kerry, had a population of 345; ten years later, it was 277. There were 22 depositors from Listowel, one depositor from Daugh, and a total of 38 depositors from surrounding civil parishes. Again, those numbers of Irish emigrants to New York would have been far higher between 1850, when the Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank opened, and 1858, when it closed.

John Sullivan, County Cork

John Sullivan. (Image via Victoria Cross Online Courtesy Mark Green)

The fourth VC recipient is John Sullivan, born in Bantry, County Cork, on April 19th, 1830. Mark Green correctly, once again, points out the need for these young men to escape the effects of the Famine— "from a young age, John was determined to escape the troubles of the Irish Potato Famine and decided to enlist with the Royal Navy."

On April 10th, 1855, Sullivan volunteered to place a flagstaff in a position to obscure a battery from enemy soldiers. According to Mark Green, "On reaching the mound, he looked both ways to make sure he was on a direct line between the British guns and the Russian battery. He then proceeded to use his hands to make a hole for the flagstaff and then collect stones and earth to bank it up. During this action, he was exposed to a continuous fire from some Russian sharpshooters posted not too far away. Sullivan decided to stick to his task despite the risks, and completed it."

This act of bravery won him the Victoria Cross. Again, more acts of bravery awarded him "the Legion of Honour, Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, Sardinian Medal, Royal Humane Society Medal, Turkish Medal, and Crimean Medal with two clasps," according to Green.

Bantry had a population of 4,082 in 1841. By 1851, it had dropped to 2,943. According to Anbinder's Moving Beyond Rags to Riches, the closest town to Bantry was Kenmare, and "Several thousand residents of Kenmare and the surrounding parishes fled to America during the Famine years. The emigration was funded initially by the district's main landlord, the Marquis of Lansdowne, but subsequently by remittances sent back to Ireland by those first emigrants." There were 25 EISB depositors from Kenmare and upwards of 200 from civil parishes surrounding Bantry and Kenmare.

John Sullivan was awarded the VC on February 24th, 1857. He was present in Hyde Park when Queen Victoria gave out the first medals for bravery in the Crimean War on June 26th, 1857. Sullivan worked for some time as a boatswain at Portsmouth Dockyard and, after many years, returned to Ireland. Having fallen on hard times, he died by suicide on June 28th, 1884, in Kinsale. He is believed to be buried in Ballyfeard Cemetery in Cork.

Luke O'Connor, County Roscommon

Luke O'Connor. (Image via Victoria Cross Online Courtesy Mark Green)

Our fifth and final VC recipient from the Crimean War is Luke O'Connor from County Roscommon. The same Luke O'Connor in the painting at the top of this article.

Born in 1831 near Elphin, Sir Luke O'Connor's life was far from pleasant in his early years. As per Mark Green, "The family were very poor, and the O'Connor's were evicted from their family farm for non-payment of rent, and James decided to emigrate the family to North America in 1839, when Luke was 8. Sadly, tragedy struck, as James O'Connor died at sea on the voyage, and his mother and baby brother both died of cholera shortly after arriving at Grosse Isle, Quebec. Luke then returned to Ireland though some of his siblings remained in North America."

At 17, O'Connor joined the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in 1847, having left the town of Boyle in Ireland and moved to London. He was recognized as a good soldier. And by 1850, he was promoted to Colour Sargeant. Only six days after arriving in Crimea, Luke O'Connor would perform his act of bravery, winning him the VC. As per Mark Green- "O'Connor would be involved in the Battle of Alma, where he would distinguish himself to be awarded the Victoria Cross. During the Battle, a young Lieutenant Anstruther was carrying the Regimental Colours. Suddenly, Anstruther was hit and killed, and without hesitation, O'Connor (himself wounded in the chest) grabbed the colours, raced to the head of the Regiment, and planted the Colours on the redoubt before those of the enemy, who were near at hand, could realise their perilous position. The Welsh Fusiliers were inspired by O'Connor's actions and the bayonet charge was a success." O'Connor was wounded but returned to fight at the Battle of Sebastopol.

Luke O'Connor was present in Hyde Park to receive his Victoria Cross from Queen Victoria, along with 61 other men, in 1857. In addition to the VC, he was awarded the Indian Mutiny Medal. O'Connor continually rose through the ranks, retiring in March 1887 as a General. He died on February 1st, 1915. He was buried at St Mary's Roman Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green.

In 1841, the population of Elphin was 1,551, and in 1851, it had decreased to 1,229. There were 9 EISB depositors from Elphin and at least 60 from nearby parishes; again, that number of actual immigrants in New York would be higher. However, Sir Luke O'Connor seemed to have a better last half of life than his first humble beginnings.

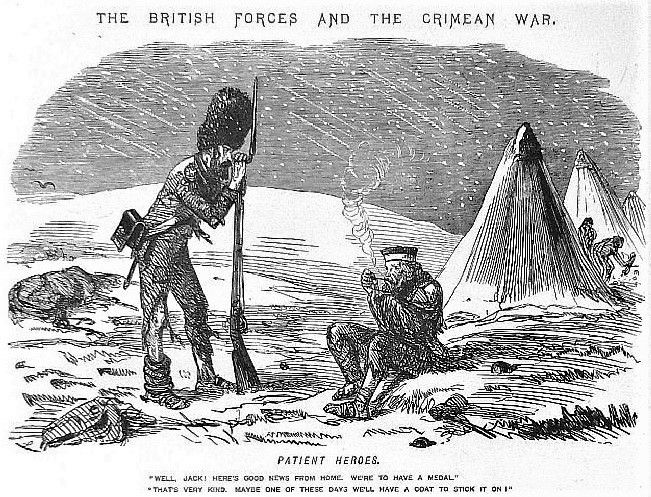

Two British soldiers in the Crimea comment they will receive a medal, but need warmer clothes in the Russian winter. (John Lee in Punch Magazine December 1854 - Public Domain)

We can only guess these men enlisted because of their humble earlier existences. Life was not easy for many in rural Ireland at the time. We know that recruitment practices were happening all around Ireland leading up to the outbreak of the War with Crimea. Some of the enlistment procedures were unethical, getting young men drunk and then signing them up for the Queen's shilling, as some researchers have suggested. Recruitment in rural Ireland was happening at markets and fairs. Many young men did enlist to "escape," as many historians have already stated.

After returning to Ireland, which many men did after the Crimean War, life was still difficult, as Murphy points out in his article about the Nenagh Mutiny mentioned earlier. Let's look at one Nenagh man, Patrick Darbison, born in 1827 and died in 1909, who served in the Crimean War and the India Mutiny. We learn from his obituary he was "very fond of relating his experiences in active services."

The Nenagh Guardian obituary of Patrick Darbison, dated July 22nd, 1909, elaborates even further on the life of these Irish men fighting in the Crimean War-

"AIl through the Crimean War and Indian Mutiny, and notwithstanding that, he took part in several battles and minor engagements, he came without a scratch. Such is the fortune of war; one man is, perhaps, killed the first time under some petty little engagement, while another, who bears a charmed life, courts death continually and escapes."

The obituary describes the life of most Irish men fighting in the Crimean War. "Hard life, miserable pay, ill-fitting and unsuitable clothing, floggings, and other rough treatment, the order of the day…. What a tough little fellow the Irish soldier was in those days."

Indeed, they were tough and brave.

Works and Websites used for research for this article:

- The Battle of the Breeches: the Nenagh Mutiny by David Murphy

- Irish Soldiers in the British Army, 1792-1922: Suborned or Subordinate by Peter Karsten

- British Military Recruitment in Ireland During the Crimean War, 1854-56 by Paul Huddie

- Pageantry or Propaganda? The Illustrated London News and Royal Visitors in Ireland by Margaret Cappock

- Victoria Cross Online by Mark Green

- Beyond Rags to Riches by Professor Tyler Anbinet and others

- The Great Irish Famine by University College Cork

My thanks to Mark Green for allowing me to use photos from Victoria Cross Online.

Quotes are cited accurately, without modification for spelling errors.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments