Joseph Campbell, an Irish American scholar, traced the notion of romantic love back through cultures and landed at Irish mythology.

"Marriage is not a love affair. A love affair is a totally different thing. A marriage is a commitment to that which you are. That person is literally your other half. And you and the other are one. A love affair isn’t that. That is a relationship of pleasure, and when it gets to be unpleasurable, it’s off. But a marriage is a life commitment, and a life commitment means the prime concern of your life. If marriage is not the prime concern, you are not married.....When you make the sacrifice in marriage, you're sacrificing not to each other but to unity in a relationship." - Joseph Campbell

When the Irish American scholar Joseph Campbell was growing up in New York City, he was a regular visitor to the Natural Museum of History, where he had discovered Native American peoples, and their metaphorical systems, or what we call mythology. This led the young man to pursue his own knowledge, and dig into his own soul.

It brought him to his own heritage, where he discovered ancient Irish mythology and James Joyce's modern Irish mythos, Finnegans Wake. He used Finnegans Wake and the Celtic myths of Arthur to unlock the universal mythology of the human unconscious. Finnegans Wake is littered with a dictionary-sized Gaelic Irish vocabulary and much talk of Fionn Mac Cumhaill (Finn Mac Cool) who was the hero of the Fenian cycle or the Fiannaidheacht wherein some of the earliest romantic love themes and poetry were composed.

For Campbell, as for William Butler Yeats, the ancient Irish had achieved a Tibetan-like culture, one that had opened into the seventh chakra. In ancient Ireland, Yeats had found a path to nirvana, not apocalypse, as he wrote in 'Under Ben Bulben:

"Cast your mind on other days

That we in coming days may be

Still the indomitable Irishry."

In the same poem, he spurs Irish poets to knowledge of our ancient civilization. Campbell thought the high crosses woven with knots ascending to the sun circle analogous to the chakra diagrams that a meditant uses to achieve the bliss of transcendence.

It is from this spiritually-advanced culture that a unique theme of romantic love emerged.

One of the most beautiful genres of ancient Irish literature was the story of runaway lovers, such as Diarmuid agus Gráinne, or Tristan and Iseult, and many others. The classic Irish story tells of a princess that gives up the comfortable life as a king's wife, to be with her true lover. The lovers are hunted for they have betrayed dharma or social duty--such as that of the betrothéd to her king, or that of the best soldier to his lord. The lovers would rather be hunted and have a terrifying existence in the wilderness, with only their love to keep them alive, than to be with anyone else than each other, even if it means betraying the king and all society.

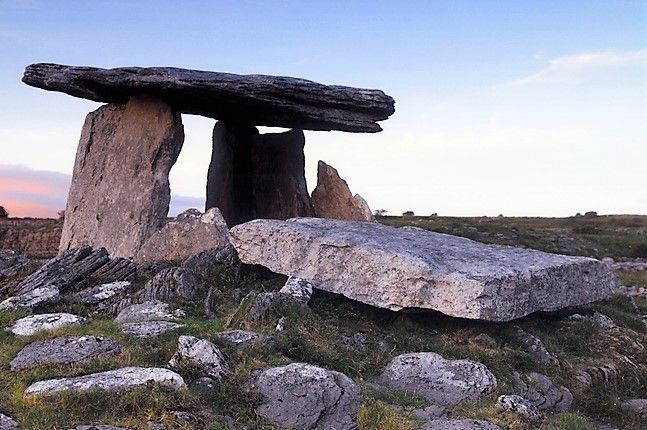

Ireland is still bestrewn with monuments to this kind of love-above-all. The great dolmens such as found in the Boirinn (the Burren of County Clare, Clár) are to this day, called Leaba Diarmuid agus Gráinne, or the bed of the lovers. It is also called Poll na mBrón, or the hole of sorrows, to invoke the emotional terror of their time together in love, chased like animals by the king they have betrayed to be together. Infused into the Irish landscape, are these megalithic testimonials to the lovers that break all conventions and laws to be together.

Poulnabrone Dolmen, The Burren (Getty)

In later traditions, the leaba or megalithic "Gráinne beds" were places where young lovers would copulate, and so were scandalously avoided by polite society.

Campbell (his name means cam béal or crooked mouth in Irish) followed the story of Diarmuid and Gráinne into more modern European literature.

When the Norman military aristocrats invaded the Celtic lands, they subsumed the Gaelic and Welsh bards, poets, and filí that knew the canon of Celtic literature by heart and could recite great heroic epics from memory like had been done in the Bronze Age of Homer. When translated into French, the Celtic stories became contemporary to the Middle Ages, when courts and ladies, and royalty looked and felt more like the familiar Arthurian legends we know well today.

The everlasting cauldron found in the story of Brann, my namesake, for example, became the Holy Grail, and was Christened to go with Medieval norms. The Mórrigan goddess of death became Morgan Le Fay, a more manageable fairy. The old Celtic warrior King Finn became Arthur, a Frenchified (and later Anglified) version of Irish and Welsh legends, confused also with historical Welsh leaders who fought Anglo Saxon invasion and were given the patronym of "bear" or "art" in the Welsh language.

Diarmuid, the soldier or Fenian, became Lancelot, the betrayer of duty for romantic love. And Gráinne, whose name comes from the Irish grian, or sun, became Guinevere in the French, she who betrays her duty as wife betrothed to a political ally, for the true experience of life, a life in the arms of her love of all loves, no matter the price.

* Originally published in 2011. Updated in February 2023.

Comments