One of the problems with the history of the Irish War of Independence is that so many of the participants never got to tell their story—some died, some remained mute—so many of the “facts” were told secondhand.

But there is one eyewitness who came forward to tell the terrible truth about what really happened in that pivotal year of 1920. His name was Vincent Byrne, Old IRA, and a member of the Squad, Michael Collins’ legendary “Twelve Apostles.”

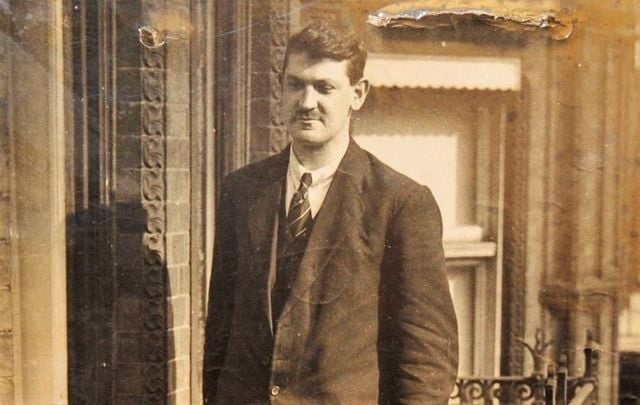

I first came across Byrne in the RTÉ/BBC history of Ireland back in the 1970s. Vinny came on to the screen, a delightful little Irish gnome, laughing and telling tales. It was when he came to the events of Bloody Sunday that the shock began.

On November 21, 1920, at precisely 9 a.m., members of Collins’ Active Service Unit (ASU) Squad entered buildings, most in Dublin’s now trendy D4 postal district, and shot dead 14 members of the British Secret Service. Byrne’s assignment that morning was the building at #38 Upper Mount Street, a block removed from Merrion Square and framed by St. Stephen’s Church of Ireland, fondly known as “The Pepper Canister” because of its unique architecture.

Perhaps the best way to understand and appreciate Byrne’s contribution to the cause of Irish freedom—and to understand the strategy of Michael Collins—is to read his complete witness statement at the Bureau of Military History which Byrne gave on September 13, 1950. It is 75-pages long and it reads like a thriller.

Byrne joined the Irish Volunteers in January 1915 at the age of 14. He was a member of the Volunteers 2nd Battalion, Dublin South. One of his officers was Mick McDonnell who would become the first leader of Collins’ Squad.

On Easter Monday 1916, Byrne assembled on Stephen’s Green, ready to march over to Jacob’s Biscuit Factory and strike a blow for Irish freedom. When spotted by a Volunteer officer, he was told to go home, probably because of his age.

“I started to cry,” said Byrne in his statement, “because I was being sent home. I met section commander Mick Colgan on my way down Grafton Street and he asked me what was wrong with me. I told him what Lieutenant Shiels has said to me. He said: ‘Come along out of that, and don’t mind him.’ So I paraded at Stephen’s Green with the remainder of the company and was armed with a .22 rifle.”

Byrne spent the week in Jacob’s and with the surrender escaped to his home on Anne’s Lane, just off South Anne Street, near the top of Grafton Street. A week later he was arrested by the British at home and taken to Richmond Barracks where he was fingerprinted before being released about a week later with other youngsters, including future Taoiseach Seán Lemass, who would also be a member of the Squad on Bloody Sunday. (It is interesting to note that the rebels were fingerprinted, but no mugshots were taken, which would come back to haunt the British because they did not know what many of the key players looked like—especially one Michael Collins.)

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

In another ironic twist, a short six years later Byrne, then a Commandant-Colonel in the new National Army, would be the commanding officer of the same Richmond Barracks.

Byrne recounts how he became a member of the Squad after being recruited by Mick McDonnell: “‘Would you shoot a man, Byrne?’ [asked McDonnell] I replied: ‘It’s all according to who he was.’ He said: ‘What about Johnnie Barton?’ ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘I wouldn’t mind’—as he had raided my house. So Mick said: ‘That settled it. You may have a chance.’”

Byrne goes on to relate his many adventures, including trying to shoot Lord French, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, on several occasions. He relates how they stole the Royal Mails to obtain intelligence as it related to the dealings at Dublin Castle.

By most historical accounts Collins set up his private ASU, his Squad, in September 1919. (There is an account of this in the movie Michael Collins where Collins is recruiting the members and says if you don’t want to join, it won’t be held against you. At the end of this meeting, a volunteer holds up his hand and says something to the effect: “Would we have gotten out of here alive if we said ‘no’?” Liam Neeson laughs and refers to his questioner as “Vinny.” Guess who the imp was?)

The idea behind the Squad was relatively simple. In collaboration with Collins' intelligence operation located at 3 Crow Street, its purpose was to identify and eliminate British spies and touts. Assassinations could only be ordered by Collins himself, or, in his absence, Richard Mulcahy, Chief-of-Staff of the IRA, and Dick McKee, commandant of the Dublin IRA brigades.

Members of the Squad hung out at various offices around Dublin called “Dumps” because that’s where they would dump their guns after a job. A frequent visitor was Collins himself, as Byrne recalled: “The ‘Big Fella,’ Mick Collins, visited us at least twice a week. Notwithstanding the enormous amount of work he undertook, he found time to visit his Squad. The moral effect of his visits was wonderful. He would come in and say: ‘Well, lads, how are ye getting on?’ and pass a joke or two with us. He was loved and honored by each and every one of us, and his death was felt very keenly by the Squad. I am proud to say that Mick stood by us in our hard time, and that every single member of the Squad stood by him in his hard times, without exception.”

Perhaps the highlight of the statement is his involvement in the events on Bloody Sunday. His targets that morning were a Lieutenant Bennett and a Lieutenant Aimes. They were living at 38 Upper Mount Street (the address is misidentified in the statement as #28). Byrne rounded up the two men and brought them to the back room. He stood them on a bed together. “When the two of them were together, I said to myself ‘The Lord have mercy on your souls!’ I then opened fire with my Peter [hand gun]. They both fell dead.” If that wasn’t enough excitement, Byrne and his men ran into a shoot-out with British agents as they were escaping. They exchanged fire and Byrne and his men got away.

Byrne relates many adventures, including the shooting—which dismayed and incensed Winston Churchill—of Alan Bell, the bank examiner brought in by the British to find Collins’ National Loan; the elimination of Willie Dolan, a porter at the Wicklow Hotel who was a British tout [unbelievably Collins gave his widow a pension because she believed that he had been killed by the British]; and the greatest Eamon de Valera fiasco—and triumph—in Irish history, the burning of the Customs House in May 1921, where Byrne narrowly escaped capture.

After the establishment of the Irish Free State, Byrne left the army, but remained active in Old IRA activities, serving as an ambassador to both sides of the conflict. Nearly one hundred years after his adventures, it’s a wonder that Hollywood hasn’t come a-calling to tell the story of Michael Collins’ most colorful Apostle, Vinny Byrne.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family," "Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising" and "Irish Miscellany" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his website and Facebook page.

*Originally published in April 2017, updated in 2025.

Comments