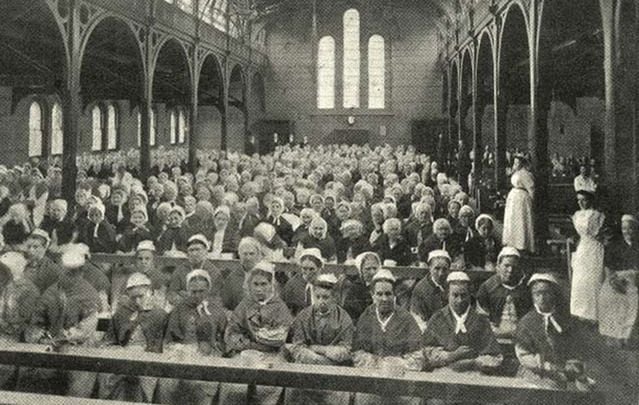

The workhouse was the most feared institution in 19th-century Dublin.

Though the workhouse was to be avoided at all costs, harsh times drove many of the city’s poor through its doors. As the Dublin workhouse records available on the family history website Findmypast testify, this accounted for a huge swathe of the population.

The workhouse was the only form of poor relief available – the historical equivalent of today’s welfare system. Because society, governed by the rich, worked on the assumption that poverty was one’s own responsibility and a symptom of the failure to provide for oneself, the workhouse was also seen as a center for moral reform. Life inside was designed to be brutal, to ensure that only the neediest sought it out.

Upon entering the workhouse, you were stripped and washed. One small bath would be shared between a large group, so you’d hope to take your turn first. You were then dressed in the coarse, stiff workhouse uniform, and given hard wooden clogs.

The workhouse day started at 6 am. Breakfast was eaten at 6:30 am. This would most likely be stale bread or gruel, or porridge. There were regulations as to what constituted a workhouse meal, however underpaid masters often cut corners to make the food “go further”. After eating, inmates were set immediately to work, at 7am. A girl under 15 could be sent to assist the matron in the infirmary, but everyone over 15 might be subject to backbreaking labor. Anyone who refused to work went without their next meal. Refuse twice, and you were punished at the discretion of the overseer.

Lunch was taken between 12 and 1 pm, and then work was resumed until 6 pm when supper was eaten. This lasted half an hour, after which there might be more work if it was light. Otherwise, there was an hour of leisure time before bed at 8 pm. The only days free from work were Sundays, Good Friday, and Christmas Day. Cards or games of chance (too similar to gambling) were forbidden, as was smoking or drinking.

The poor were inconvenient, and their lives were worth less than nothing. While conditions in the 1800s were brutal, they were still an improvement on the previous century. The Foundling Hospital in Dublin saw a total of 5,216 infants sent to the infirmary from 1791-1796. Just one recovered. The babes were stripped upon arrival and put into old clothes – the ones they had arrived in. They were then laid side by side in filthy cradles – five or six apiece, overrun with vermin, and covered with vile blankets deemed “unfit” for any real use. At intervals, the nurse would pass around a bottle of “medicine.” The “medicine” was to help them die.

Despite the horror, they experienced once inside, for thousands the workhouse was all that stood between them and starvation. The Great Famine saw dependency on the workhouse skyrocket, and a huge proportion of the population were desperate enough to brave life within its walls.

To discover whether your ancestors were among the thousands who survived the horrors of the workhouse, go to Findmypast, and explore the new Dublin workhouse records today.

*This article was produced as part of a previous partnership with Findmypast. For more stories on Irish genealogy, click here.

* Originally published in May 2015, updated in 2024.

Comments