Taoiseach Enda Kenny's announcement in the U.S. last week that the Irish government will hold a referendum on whether Irish citizens living abroad should be given a vote in our presidential elections came as a surprise to people at home. It's not new, of course, but trotting it out again just now was unexpected.

It was typical Enda, a grandiose but vague gesture that may end up meaning very little -- and could cause all sorts of problems.

Not that he cares. He was on his honorary last lap as taoiseach and needed something to butter up the Irish in the U.S. Votes for emigrants sounded good, even though there was no detail and no one knows how it would work or what the consequences might be. Not that this bothered Kenny, who made the announcement like a magician at a kids' party pulling a rabbit out of a hat.

The reality is that the taoiseach was recycling an old idea that has been considered here at various times over the years by both study groups and governments. And it's never come to anything.

Will it be different this time? Probably not, although much will depend on the extent of the proposal to be put to the people here in a referendum.

There is supposed to be an options paper on votes for emigrants from the government next month -- but then that was supposed to be published last year and we're still waiting. Since the taoiseach has jumped the gun on the matter, it may well emerge this time, but don't hold your breath about anything happening quickly after that.

As we said, the proposal could create major difficulties and be more trouble than it's worth. The devil will be in the detail and we don't know any of that at this stage.

Read more: Irish leader announces referendum - Diaspora, Northern Irish citizens to vote in presidential races

In fact, it seems likely that Enda has not thought through the detail either. It will be his successor who will have to grapple with the implications and complications, so why bother?

The reaction in Ireland to Kenny’s announcement was uneasy. Straight away we had people here quoting the slogan from the American revolution of No Taxation Without Representation. Except that they inverted it into No Representation Without Taxation.

How is 3.6m voters outside Ireland not swamping our own 3.3m voters? It's absolute lunacy https://t.co/dQnyAyZnBi

— Keith Mills (@KeithM) March 24, 2017

One can argue about how relevant that is in this case. Unlike in the U.S., the Irish presidency is a ceremonial role with no real power. Extending the vote for the Irish president to the diaspora, therefore, can be seen as symbolic, a somewhat empty gesture. Since there's no executive power involved, tying votes for emigrants to paying tax in Ireland would appear to be unnecessary.

But there's much more to it than that. Kenny’s surprise parting gift to emigrants raises questions about much more than taxation.

For a start, there's the slippery slope consideration. Some of those campaigning for change will not be satisfied with limiting votes for emigrants to the presidency (see votingrights.ie, etc.) They might take that as a start but they also want some representation in the Irish Parliament, which is a different matter altogether since decisions that are taken there affect the lives of the people who live here.

Even on the issue of who can vote for president, there is some nervousness. The Irish presidency may be a ceremonial role but the holder of the office represents the country and frequently speaks as the voice of Ireland on the international stage.

Who holds the office is therefore of importance and the choice is a sensitive one. How far we want to extend the vote to choose our president has to be considered carefully. Already concerns have been raised about how informed some of the new voters would be and what kind of agendas they might have.

But the biggest problem in all this is the numbers. What the taoiseach proposed in his speech in Philadelphia was extending the vote to Irish citizens living abroad. That would include the estimated 1.7 million people born in Ireland who now live abroad. It would also potentially include the 1.9 million people in Northern Ireland who automatically have the right to Irish citizenship since they were born on the island of Ireland.

And then there is the question of the wider diaspora, with some 70 million people around the world with Irish ancestry, around 40 million of whom are in the U.S. Under our rules, any of these people with an Irish-born parent or even one Irish-born grandparent is entitled to Irish citizenship and, if they register, would be entitled to vote in presidential elections. That could be another million or two -- or more.

These numbers are scary for people here, even if it is likely that only a small proportion of these potential citizens might actually go through the registration process and vote.

But even if only five percent did so, it would have a huge impact. In the last presidential election here in 2011, 1.7 million people voted. If the electorate is extended as proposed, that number could be equaled or surpassed by voters outside the country in the future. Of course, it's extremely unlikely that would actually happen, but it is possible.

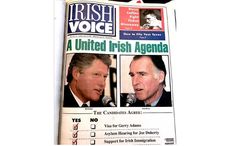

The Northern Ireland aspect in all of this is a particular worry. Sinn Fein got almost a quarter of a million votes in the recent Assembly elections there. If those voters were asked by the party to register and vote in a presidential election in the south -- especially if Gerry Adams was the candidate -- we can be sure a significant number would answer the call. Given how close presidential elections here can be, that could be a deciding factor.

There is also the fact that Sinn Fein is by far the most organized and financially supported Irish party in the U.S. and could mount a similar campaign there to get people with an Irish parent or grandparent to register and vote. And if Adams was a candidate that could develop real momentum given his appeal over there.

Before those of you in the U.S. who are not fans of Adams start choking on your breakfast, we should point out that there is unlikely to be any change before the presidential election which is due here next year. So the earliest it would happen, assuming a referendum is passed later next year, would be 2025 (our presidents serve seven-year terms) when Adams would be 77. But even if he did not run, there are other prominent Shinners who could take his place.

This prospect, however unlikely, would not go down well with the majority of voters here. Some people in Fine Gael (which has never won the presidency) have been wondering whether the taoiseach gave it much thought before making his announcement since it could scupper their chances in the future.

Read more: Finally, Northern Ireland says ‘Yes’ after decades of ‘No’

The likelihood is that Kenny, who is as cute as they come on voting matters, knows very well what is involved. He knows that if a referendum is to have any chance of passing here the proposal will have to be quite restrictive.

The sensible thing would be to limit the vote to people who were born in the Irish Republic (therefore not including Northern voters) and who have lived abroad for not more than 10 years. These relatively recent emigrants from the south of Ireland would be most attuned to the issues here and to the way the country is developing. And the president they would vote for would reflect that.

Excluding the North might be contentious for traditional constitutional republicans here, although presumably, Fianna Fail would see the threat to their own presidential candidates in the future. It would also avoid the presidency being hijacked as another stepping stone on the path to a united Ireland.

With Sinn Fein's strong performance in the Northern election a few weeks ago and Brexit coming down the tracks, we have enough nonsense being talked about a united Ireland already without adding to it.

Whatever about extending votes for the presidency in a limited way as a gesture of inclusion to our emigrants, the case for wider votes for the Irish parliament is really a non-starter. Even the idea of limiting the number of seats in the Dail to be elected by emigrants to half a dozen or less is questionable given the influence small groups now have in our closely balanced political situation -- something likely to continue for some time into the future.

Comparisons with the 100-plus countries who offer votes in their general elections to emigrants may be superficially convincing. But they ignore the reality that Ireland, because of its history and the huge scale of its diaspora, is unique.

The number of potential voters abroad is so large in relation to the population here that it could swamp the votes of people who actually live here. That cannot be justified.

Comments