They say that politics makes strange bedfellows.

Well, two of the oddest ducks to share the same Fenian bed were Sir Roger Casement – executed 107 years ago today in London – and John Devoy. If you read Irish history you would be led to believe that Devoy, the leader of Fenianism in the United States at the time of the Easter Rising, probably loathed Casement.

You could not find two men more different in background: Casement—Protestant, knighted for his work in the British Foreign Service, and a latecomer to the nationalist movement and Devoy—Catholic, imprisoned for his participation in the Rising of 1867 and banished to America where he demonstrated his daring by rescuing fellow Fenians from an Australian penal colony using the American ship, the Catalpa.

Devoy became the driving force behind the new militant nationalism that spread throughout Ireland through the Gaelic League and the eventual establishment of the Irish Volunteers. Devoy supplied money and ideas to keep the movement afloat. He also nurtured and groomed rebels in exile in New York—like 1916 martyr Tom Clarke—for their return to Ireland.

Devoy did not meet Casement until 1914 when he was 74. By that time Devoy had failing hearing and eyesight

Based on comments from those on the Irish side of the Atlantic, you would think that Devoy and Casement shared no common ground. “Casement had come into things national,” Kathleen Clarke, Tom’s widow, recalled in her autobiography, 'Revolutionary Woman,' “and Tom knew very little about him. Naturally, he had no cause to place much confidence in him; and the fact that he had been knighted by England in recognition of services rendered made Tom suspicious of him. Casement was not long enough in nationalist things in this country to prove his genuineness.” Joseph Plunkett’s sister Geraldine’s opinion was brutally stark: “John Devoy simply hated him,” she wrote in her autobiography, "All in the Blood."

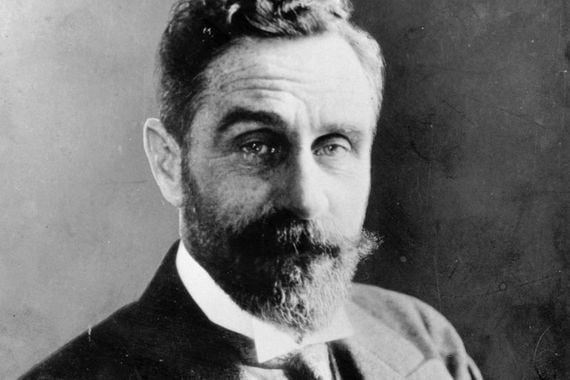

Roger Casement.

With the outbreak of the Great War, Casement landed in New York. Devoy was suspicious of Casement because he sided with John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, in Redmond’s takeover of the Irish Volunteers in 1914. This may have also been the reason why Tom Clarke didn’t trust Casement and it wouldn’t be a shock if Clarke relayed this opinion to his old friend, Devoy, in New York.

Oddly enough, Devoy’s autobiography, "Recollections of an Irish Rebel," shows an affection for Casement that one would not expect from the tough old Fenian jailbird. The book was not published until a year after Devoy’s death in 1928. (The interesting thing about the book is that it basically stops after the Easter Rising. There is not one mention of Eamon de Valera, Michael Collins, or the Treaty.)

Although he was suspicious of Casement because of the John Redmond/Irish Volunteers fiasco and highly dubious of his plan to seek German help for the coming uprising, Devoy introduced Casement to his German contacts (Franz von Papen—future stooge of Adolf Hitler—was a prime New York contact for Devoy), gave him an immense amount of money (probably in excess of $10,000), and packed him off to Europe.

Devoy did so with reservations because he did not trust Casement’s traveling companion, one Adler Christensen. “[I] missed the fact,” wrote Devoy, “that the acquaintance between the two was only of a few weeks’ duration. Had I understood that, I would have objected strongly to Christensen’s going as Sir Roger’s companion.”

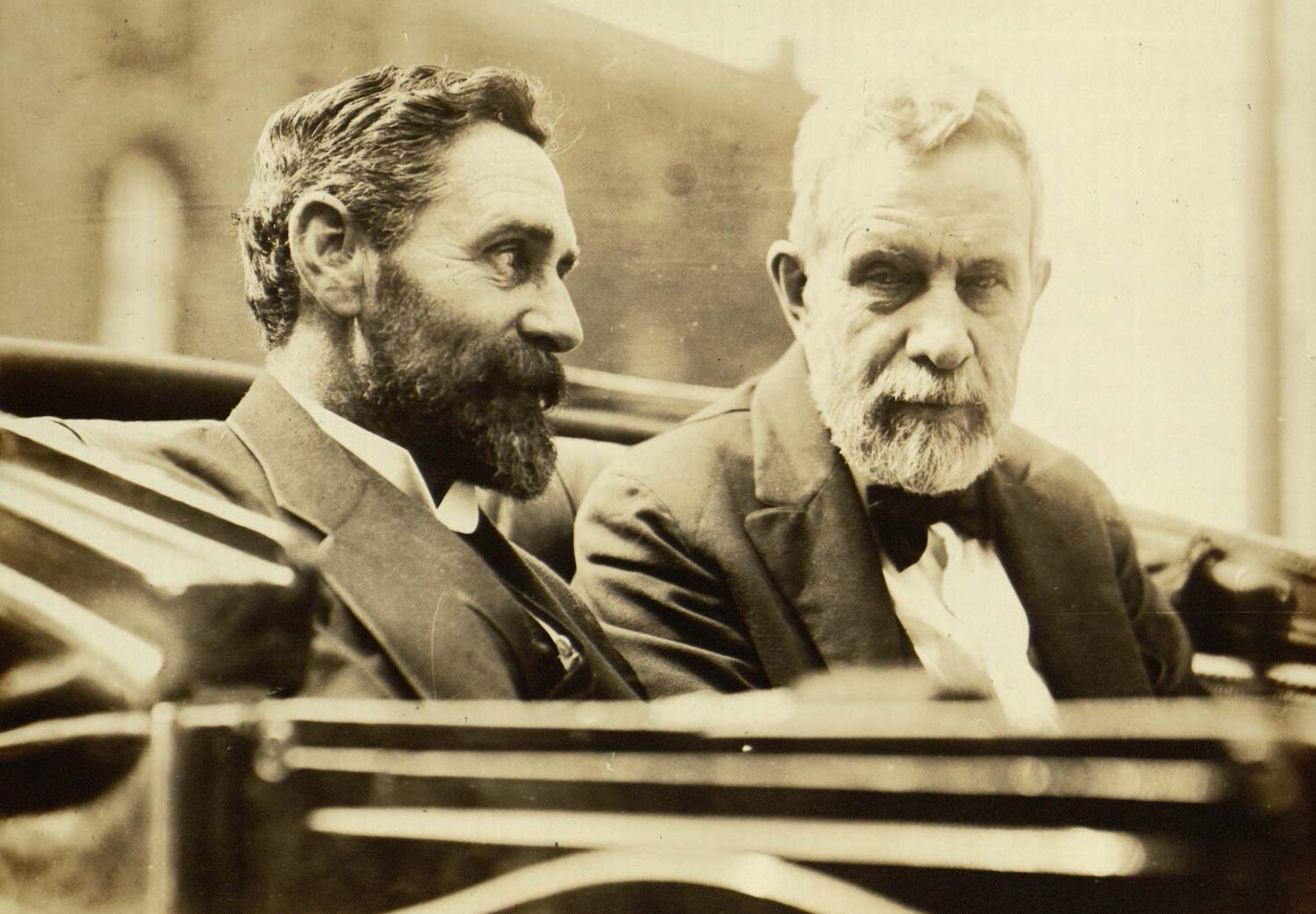

Roger Casement and John Devoy.

It is thought that Christensen might have been a British agent, maybe a German agent, or even a double-agent playing both sides. He may also have been Casement’s lover. “Christensen…double-crossed us,” said Devoy, “…[and] proved himself a trickster and a fraud…”

Devoy is blunt in his assessment of Casement and his work in Germany.

“Casement’s mission to Germany had three main objects: First, to secure German military help for Ireland when the opportunity offered. Second, to educate German public opinion on the Irish situation, so that the people would stand behind their Government when it took action in favor of Ireland. Third, to organize, if possible, Irish prisoners of war into a military unit to take part in the fight for Irish freedom. Casement did his best in all these things, but did the first ineffectively, succeeded admirably in the second, and failed badly in the third.”

Devoy may have been old, frail and crotchety, but he was an excellent judge of character. While Tom Clarke may have been suspicious of Casement’s motives—he probably thought him a British agent—Devoy took Casement for what he was—a true patriot—with a strong shake of salt: “While a highly intellectual man, Casement was very emotional and as trustful as a child. He was also obsessed with the idea that he was a better judge than any of us, at either side of the Atlantic, of what ought to be done (though he was too polite and good-natured to say so), and he never hesitated to act on his own responsibility, fully believing that his decisions were in the best interests of Ireland’s Cause. This created many difficulties and embarrassments for us.”

“Practical politics he did not understand,” wrote Devoy, “but the end to which the practical politician, the statesman and the soldier should devote their efforts he understood most thoroughly. He was an idealist, absolutely without personal ambition, ready to sacrifice his interests and his life for the cause he had at heart, but was too sensitive about the consequences to others of his actions.”

When Casement was in London awaiting trial, Devoy selflessly donated $5,000 he had just received from his brother’s estate in New Mexico to Casement’s defense. In his autobiography he slammed the British for their whispering campaign about the “Black Diaries,” Casement’s supposedly notoriously graphic descriptions of his homosexual romps on two continents—which may or may not have been a fabrication of the British Secret Service—as “foul and slanderous propaganda to arouse public opinion in America against him.”

He wrote of Casement’s demise at the end of a rope on August 3, 1916: “Thus ended the career of one of Ireland’s noblest sons.”… [H]e was withal one of the most sincere and single-minded of Ireland’s patriot sons with whom it was my great privilege to be associated. His name will ever had a revered place on the long roll of martyrs who gave their lives that Ireland might be free.”

High praise indeed from the man Patrick Pearse called “the greatest Fenian of them all.”

---

Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

*Originally published in August 2016. Updated in August 2023.

Comments