Pittsfield, Massachusetts: My Mom, who passed away in October, was happiest at Christmas with her eight children scattered about the house. Mickey and Mary, the eldest, who carried the hopes of our family into the New World after we had emigrated from England in 1953; her three “rapscallions” -- Jimmy, myself, and Dermot -- on best behavior for the season; and the three American-born -- Eileen, Anne Marie, and Kieran -- their faces glowing like Advent candles. Dad, too, was full of inexhaustible mirth, bringing home fruitcakes the weight of bowling balls -- gifts from the nuns at St. Luke’s Hospital.

Christmas cards from the Old Country also brought joy to Mom. At the thump of the mailman’s boots on our front porch, we three musketeers would race out in bare socks to retrieve them, and run back inside gleefully to stack them up on Mom’s aproned lap, while claiming the colorful stamps for our collections. These Yuletide greetings came from Irish girls with whom Mom had nursed in England in the 1930s and ’40s -- Margaret Egan, Lizzie Dwyer, Mary Brennan, Sissy Lannon -- names that were as much a seasonal tradition as peanut brittle and ribbon candy.

Sitting in the light of our front room, Mom would relate the contents for all to hear. “Dear o’ dear, Mary Rattigan and her husband, Jim Curran, have finally settled in Wolverhampton.” Yes, it was the holidays that brought out Mom’s fond memories of her fellow nurses from County Roscommon -- young girls such as herself, called to St. Andrew’s Hospital in Northampton, England, to commence their training.

St. Andrew’s, the largest psychiatric facility in Europe, had opened its doors “for private and pauper lunatics” in 1838. Many notables received care there, from John Clare, the famous “Northamptonshire peasant poet,” to James Joyce’s daughter, Lucia. During Mom’s time, many members of the decaying European aristocracy stayed there as well.

One of Mom’s favorite patients was the Honorable Violet Gibson -- daughter of the former Lord Chancellor of Dublin -- who had attempted to assassinate Benito Mussolini in Rome in 1926, and who resided at St. Andrew’s until her death in 1956. The shot from her revolver struck him in the nose, but Mussolini took it lightly and saved her from an angry mob, saying, “Calm yourselves. It is just a simple joke with a pistol shot.” Rather than having her imprisoned, he had her committed, and the nurses at St. Andrew’s often wondered how history would’ve played out if Violet had been successful.

“Lady Gibson rarely spoke to anyone,” Mom told us, “but one morning, out of the blue, she asked if I’d help her sew little pouches into the shoulders of her black dress. She’d go filling these pouches with breadcrumbs and sit perfectly still in the rose garden, where sparrows and robins would alight on her shoulders and feed. She did this for years, mind you, and we’d often tell her that her cheeks had been caressed by the wings of a thousand birds. Our words never failed to make her smile.”

But nursing at St. Andrew’s wasn’t always a rose garden. Mom told us of a patient in Ward Three who pulled her hair so viciously that she had to soak her head in antiseptic solution for a week. But Mom refused to blame the patient for the attack, telling the matron, “It was Miss Piggott’s illness giving out, not herself.”

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

During the Blitz -- 1940-1941 -- Mom and her two sisters, Mary and Nancy, were among the nurses assigned to accompany patients to the relative safety of North Wales. They spent several Christmases at the majestic estate of Bryn Y Neuadd in Llanfairfechan. In fact, Mom’s oldest sister, Mary, would go on to marry a local carpenter, Eric Griffiths, and raise their family in this picturesque seaside town.

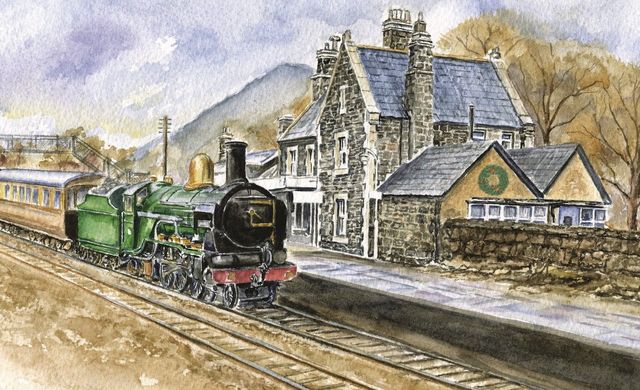

Mom often marveled at the splendor of Bryn Y Neuadd, with its ancient woodlands, Grand Lodge, and Italian gardens. But she, like many others, believed the mansion was inhabited by ghosts, and often heard the wails of bygone patients. The most haunting sound by far for Mom, however, was the whistle of the Irish Mail that hurtled on its tracks between mountain and sea shortly after midnight, traveling from London’s Euston Station to Holyhead, Wales, where it would ferry its mail and migrants across the choppy Irish Sea to the port of Dun Laoghaire, south of Dublin.

“The train’s whistle was lonelier than a curlew’s cry,” Mom remembered, as she arranged her Christmas cards on top of our small bookcase. “Especially at Christmas, knowing that some of our mates from St. Andrew’s were headed home for the holidays. When off-duty, I’d walk the terraced paths down to the railway station, hoping to catch a glimmer of them as they passed. A foolish enterprise, truly, for the Irish Mail seldom stopped at Llanfairfechan, and the lit carriages would flicker by faster than a shuffling of playing cards.

“One Christmas Eve, though, the train made a rare ‘request stop’ at the station, so I dashed down the platform like a schoolchild, wiping frost from the carriage windows and peering inside. And, sure, didn’t I come upon Molly and Ellie Ganley and, I tell you, I gave them quite a hop! All I could do was wave and blow them kisses before they were off again, leaving those Welsh coalfields for the green pastures of home.

“ ‘Twas a long walk back to Bryn Y Neuadd that night,” Mom concluded with a sigh. “Christmas in Ireland was all I pined for at the time -- morning Mass, helping Mama ready the goose, neighbors rambling in the whole day.” Her voice quavered, but she caught herself and mussed our hair with her fingers. “But what’s the use in talking? Isn’t it Christmas here in America, too! And haven’t I pies to mind in the oven?”

Now, on this, my first motherless Christmas, I imagine myself at Llanfairfechan Station, pacing its platform long before the Irish Mail is due. And, if by chance the train does stop here, however briefly, I’ll run its length as quickly as any two legs can fly, hoping to catch one last glimpse of Nurse Kelly -- my dear Mom -- smiling broadly and bound blessedly, at last, for home.

Comments