It's remarkable how many schoolteachers, poets, philosophers, and playwrights took up the cause of Irish freedom in the years before the Rising and on through the Irish Civil War.

Among the best and brightest of their generation, what is certain is that many of them were fighting not just for political independence from England, but also for something much deeper, harder to quantify, a sort of complete metaphysical restoration of the Irish psyche after colonialism.

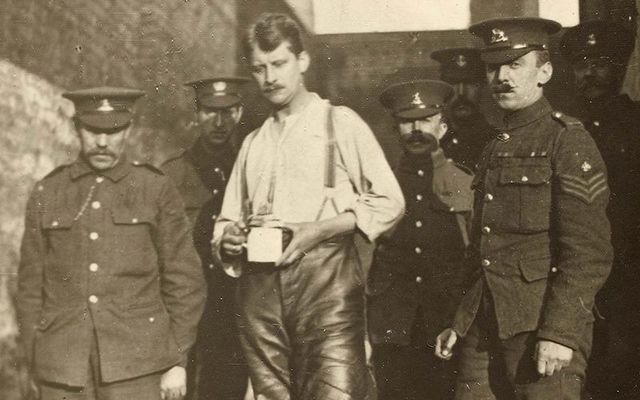

Thomas Ashe was an exemplar of the type. A revolutionary idealist with first-hand experience of the privations of Irish rural life, it's no wonder he made common cause with men like his close friend playwright Sean O'Casey, who was equally versed in the hardships of urban living.

Ashe, who was born in the Co Kerry Gaeltacht, had been a schoolteacher, as well as a member of the Gaelic League and a founding member of the Irish Volunteers. Watching his tenant farmer father deal with threatening landlords and agents in his childhood had a profound effect on him, as did the terrifying accounts he had heard in his youth about the suffering of the people during the Great Hunger (as reported to him by the still-living witnesses in his hometown).

Reading "I Die in a Good Cause," originally published in 1970, is to connect with the great national narrative that once electrified Ashe himself. Author O Luing was born only a few months before Ashe's death in 1917, and his book reminds us of the enduring power of a legacy.

Thomas Ashe was only 32 when he died (after a so-called “botched” force-feeding while on hunger strike in Mountjoy Prison). Ashe and his fellow revolutionary inmates had insisted they be categorized as political prisoners, and their hunger strikes had commenced in the hope of conceding the point.

But as so often in the story of the struggle for Irish independence, much of Ashe's legacy now comes to us from the lingering questions over who he would have been, what part he might have played in the wider national story, had his promise not been so cruelly cut short.

There is more than a hint of reverence in this clear-eyed but celebratory telling. As long as there is an Ireland, it's a story that will not age and a book that will never be out of print.

* Originally published in 2017, updated in 2024.

Comments